Arizona senators join razor-thin majority to OK health care debate

WASHINGTON - Both Arizona senators joined the majority of their fellow Republicans and voted by the narrowest possible margin Tuesday to allow debate on measures that could repeal or replace the Affordable Care Act.

Arizona sun may spur summer SAD, a rare, lonely depression

PHOENIX – Mike Johnson, a 50-year-old flight reservation agent, endures summer’s blistering heat and hours of relentless sun behind his home’s shuttered blinds, saying he loses sleep and weight.

Technology helps trauma survivors accelerate PTSD treatment, recovery

SCOTTSDALE – Traci Temple St. John suppressed the trauma of her childhood for years. Adults said they loved her, then physically and sexually abused her, she said.

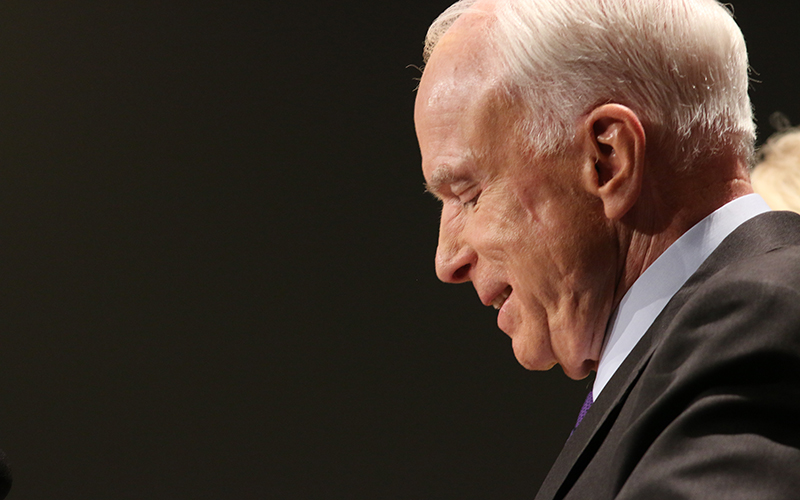

Outpouring of support for McCain comes from far – and weird

WASHINGTON - The outpouring of support following this week's announcement that Arizona Sen. John McCain has an aggressive brain tumor came from the expected Washington heavyweights, including current and former presidents, lawmakers and Cabinet members.

Advocates: Obamacare repeal would ‘painfully disrupt’ Arizona care

WASHINGTON - A Senate proposal to repeal the Affordable Care Act with no replacement plan in place "would immediately and painfully disrupt the health care system" and could force as many as 709,000 Arizonans off coverage, advocates said this week.

Flake: McCain ‘sounded great,’ as experts debate severity of condition

WASHINGTON - Sen. Jeff Flake said fellow Arizona Sen. John McCain "sounded great" in a phone conversation Monday, just three days after McCain underwent surgery to have a blood clot removed from above his left eye.

‘Paper clip’ heart implant monitors problems, alerts doctor’s smartphone

PHOENIX - David Barnard felt a pain in his chest. His vision blurry and his left arm limp, he turned to his friend.

Report: Doctors teeter on the divide between pain treatment, opioids abuse

TEMPE – Chronic pain grips Lauri Nickel every day, day after day.

Arizona protesters arrested at Flake’s D.C. office in health care rally

WASHINGTON - As calls of "Trumpcare kills" and "health care is a human right" echoed through the halls of Capitol office buildings Monday, Lauren Klinkhamer stood quietly in Arizona Sen. Jeff Flake's office and told staffers, "I don't want to die."

Researcher: LGBT couples may face depression, pressures under weight of discrimination

TEMPE – Aryana Dahlgren, a 19-year-old college student, identifies as a gay woman, but has not come out to her family.

Local protests just part of pressure aimed at Flake on health care vote

WASHINGTON - When protesters descended on Sen. Jeff Flake's office this week to demand that he vote against the Senate's health reform bill, it was just the latest in a campaign by local and national groups to pressure the Arizona Republican.

Opioid prescriptions drop, but Arizona counties still above norm

WASHINGTON - Despite recent declines in the number of opioids prescribed in the U.S., prescriptions are still three times higher than they were in 1999 - and most Arizona counties are prescribing at rates well above the national average.