PHOENIX – The Arizona health community distributed 305 million pain reliever pills last year – enough to provide 24-hour medication for every adult in the state for two weeks straight, according to the Arizona Criminal Justice Commission.

As those pills, like other medications, are taken or tossed, some of the chemicals found in them can end up in the water supply.

Chemical contaminants, ranging from prescription drugs to hygiene products, can enter the environment through landfills, flushed waste and shower drains. In the U.S., some of the most common contaminants include prescription and nonprescription drugs, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

“Even though there are probably more questions than answers surrounding this subject, it is not new,” said Jennifer Martin, a water coordinator for the Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club. “The amount of pharmaceuticals and toiletry chemicals entering the environment is comparable to pesticides, but gets a lot less attention.”

The impact these chemicals have on the environment is not well understood, and there are few studies dedicated to monitoring opioids as they move from the population to waste products and finally to the environment, said Beth Polidoro, a researcher of risk assessment, applied toxicology and environmental chemistry in the School of Mathematical and Natural Sciences at Arizona State University.

By Environmental Protection Agency standards, opioids fall under the category of PPCP, which stands for Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products. In other words, opioids are considered “daily use chemicals,” along with other types of medicines, shampoos, detergents and perfumes, said Leif Abrell, an associate research scientist in the Department of Soil, Water and Environmental Science at the University of Arizona.

The EPA regulates contaminants in drinking water considered toxic to humans. However, the disposal of most of the daily use chemicals – like opioids – aren’t regulated and are treated by wastewater treatment plants, he said. Abrell said it would be very difficult to monitor because the resources just aren’t available.

Phoenix police have installed prescription drop-off bins at precincts so people can get rid of unwanted drugs. Officer Joe Bruno and his colleagues must empty the bins once every month. However, he said they empty them about once every week because they fill up too fast. This bin at the Mountain View precinct had just been emptied. (Photo by Ryan Dent/Cronkite News)

Related:

Hundreds of sober living homes in Prescott face new rules

AZ health official: $3.6 million federal grant jump starts opioid awareness efforts in six counties

State excludes veterinarians from prescription drug database requirement

With millions of painkillers circulating annually, health and environmental officials often encourage consumers to use pill drop-off locations to dispose of unwanted or leftover pills. However, “contaminants of emerging concern” continue to show up in water samples throughout Arizona.

Between 2007 and 2009, water samples from Arizona surface water, wastewater, drinking water treatment plants and groundwater recharge sites showed 26 contaminants in a study by Chao-An Chiu, who authored the study as a doctoral dissertation, and Paul Westerhoff, professor and senior adviser on science and engineering to the ASU vice provost.

Water samples taken from the Salt River, where visitors spend summer days tubing, swimming and tanning, and other groundwater and surface water sources showed evidence of consistent contaminants, such as acetaminophen, oxybenzone and caffeine.

The Salt River watershed and Colorado River systems supply nearly 3.5 million people in metro Phoenix with drinking water, according to the study.

The study called for better tracking of contaminants in drinking water and suggested establishing a database and long-term monitoring.

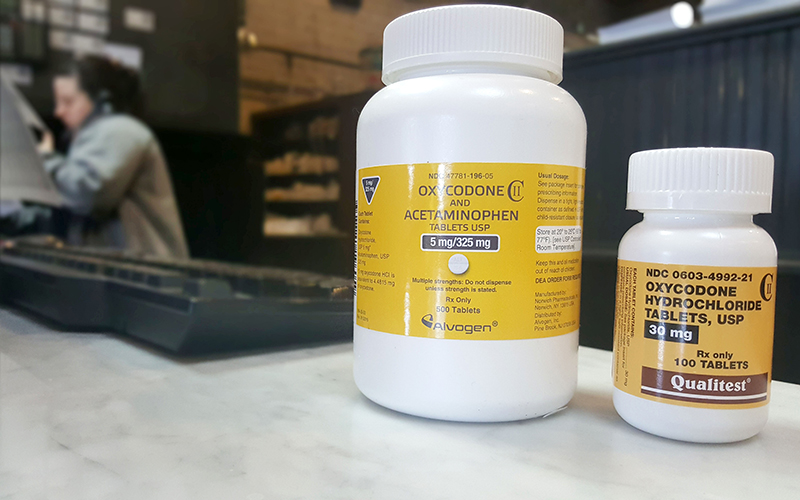

In 2015, more than 401 people died from an overdose of prescription opioid pain relievers, according to the Arizona Department of Health Services. (Photo by Gavin Maxwell/Cronkite News)

Although pharmaceuticals are not deemed an “appreciable risk to human health” when consumed via drinking water, another study in Europe found that daily use chemicals contribute more to water toxicity than high priority pollutants defined by the Clean Water Act.

On a national level, researchers from the EPA surveyed 50 large wastewater treatment plants in the U.S. to determine whether they could find traces of 56 pharmaceuticals, drugs like oxycodone and hydrocodone, in the treated water.

The survey, released in 2013, found low concentrations of these drugs in every water sample they tested. Regardless of the findings, EPA researchers estimated adults and aquatic life faced low risk from this exposure.

“Even under the extreme scenario of someone consuming half a gallon of treated wastewater per day over the course of a year, they would get the equivalent of less than a daily dose of any pharmaceutical currently in use,” according to an EPA blog. “For most pharmaceuticals, it would be less than one daily dose over the course of a lifetime.”

Cronkite News reporter Bri Cossavella contributed to this article.