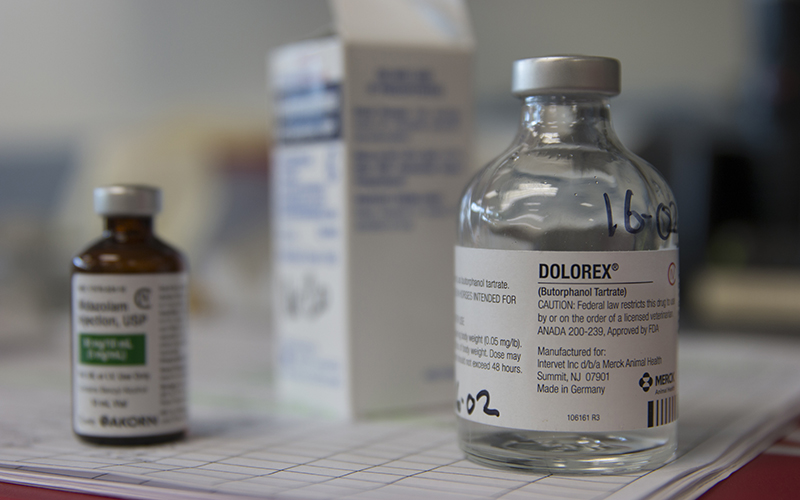

Mia, a rescued dog at Ingleside Animal Hospital, is up for adoption. It is not uncommon for veterinarians to prescribe painkillers to animals that suffer from chronic pain or that have undergone surgery. (Photo by Gavin Maxwell/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Veterinarians must register with the Drug Enforcement Administration before they can prescribe narcotics. They must go through extensive training on how to treat animals in pain. And they must keep tight controls on the narcotics they keep in the office.

But the more than 4,000 licensed veterinarians in Arizona don’t have to participate in the state’s Controlled Substances Prescription Monitoring Program, an online database designed to track narcotics prescribed to patients and help prevent “doctor shopping” and over-prescribing.

In 2007, the Arizona State Board of Pharmacy created the database as part of an effort to curb prescription drug abuse. And in May, Gov. Doug Ducey signed a bill that will require physicians to access and update the database before prescribing a controlled substance.

Arizona’s original law had included veterinarians.

Susie Stevens, a lobbyist for the Arizona Veterinary Medical Association, said it didn’t make sense to include vets. First, it’s difficult to “doctor shop” with a vet. The user would have to bring an animal to the clinic, go through an exam and pay for that.

“If you have a cat, it will be dosed for a 15-pound cat,” she said. “It’s a very difficult way for somebody to go about getting medications.”

“Veterinarians … very diligent to watch for abnormal or inappropriate requests from owners with regards to their pets for medications, such as opioids or other potentially addictive pain medications,” said Brian Serbin, the medical director and owner of Ingleside Animal Hospital in Phoenix. (Photo by Gavin Maxwell/Cronkite News)

Elizabeth Kane, executive director of the Arizona Veterinary Medical Association, said health insurance coverage for veterinary services also isn’t as common as human health insurance.

Related:

Hundreds of sober living homes in Prescott face new rules

AZ health official: $3.6 million federal grant jump starts opioid awareness efforts in six counties

Pharmaceuticals end up in water supply, AZ experts suggest better tracking

“The person bringing an animal to a veterinarian would shoulder the cost of the exam, diagnostic tests and the medication, which could be significant,” she wrote in an email.

When using the database, veterinarians would have to submit pet medications under a human’s records, and they shouldn’t have access those medical records, Stevens said.

“The regulation was rather onerous,” she said.

Ducey signed Senate Bill 1370 in 2015, excluding veterinarians from requirements to register and report.

One study published in 2014 included a 50-state survey of drug monitoring programs. Researchers found that every year, there were fewer than 10 “veterinary shoppers” nationwide that the databases could identify, and veterinarians were a minor source of controlled substances.

Unlike human physicians, vets typically dispense drugs directly from their office. (Photo by Gavin Maxwell/Cronkite News)

It is not uncommon for veterinarians to prescribe painkillers to animals that suffer from chronic pain or that have undergone surgery. In some cases, these painkillers can be opioid based. Tramadol is one such narcotic.

In veterinary school, experts said students must complete pharmacology courses and study the risks that go hand in hand with prescribing narcotics.

In fact, Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, told lawmakers on the Senate Judiciary Committee in January 2016 that veterinarians receive substantially more training on treating pain than medical doctors, according to an article in Modern Healthcare.

Fully trained vets are conscious of the dangers that addictive painkillers pose to those that have access to them, said Jason Eberhardt, an assistant professor at Midwestern University – College of Veterinary Medicine in Glendale. They know warning signs for people who might be shopping around for drugs, he said.

(Video by Dana Lewandowski/Cronkite News)

“Veterinarians are acutely aware of the problems on the human side, and we are very diligent to watch for abnormal or inappropriate requests from owners with regards to their pets for medications, such as opioids or other potentially addictive pain medications,” said veterinarian Brian Serbin, the medical director and owner of Ingleside Animal Hospital in Phoenix.

One telltale sign is when owners request to refill a pain medication early, or before the vet expects the animal to have taken it all.

In these cases, vets will check to make sure it is not a repeat situation. “I can’t say it happens frequently, but we do keep an eye on that sort of thing,” Serbin said.

Unlike human physicians, vets typically dispense drugs directly from their office. To do so, they have to be aware of the requirements set by the Arizona State Board of Pharmacy and the Arizona State Veterinary Medical Examining Board. This means keeping careful inventory of all drugs coming into and leaving the office, Serbin said.

As an additional line of defense against drug shoppers, Serbin said vets cooperate with each other, informing one another when a suspicious owner comes in with an “old dog” and requests Tramadol.

Pet owners can look up their vet’s disciplinary records by visiting the Arizona State Veterinary Medical Examining Board.