A bullseye-shaped rash is a telltale sign of Lyme disease, which is transmitted by ticks. Rates of Lyme are increasing, but experts say they lack the funding to better understand the disease, and patients still struggle to get help. (Illustration by Miguel Torres/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – For five years, Christy Annis faced debilitating nausea, vertigo, dissociation and other symptoms and went from doctor to doctor in her hometown of Tampa, Florida, trying to find out what was wrong. Tests came back negative, and practitioners started challenging whether her worsening symptoms were real.

Eventually, she was treated for small intestine bacterial overgrowth and PTSD but continued to suffer physically and mentally.

Last September, her questions were finally answered: Annis was diagnosed with Lyme disease, and a month later she moved to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, to receive a more holistic treatment that also costs less than remedies she pursued in the U.S.

“If you tell someone you have chronic Lyme, it’s like you told (them) you just have a cold, you know?” said Annis, 50. “There’s just no understanding whatsoever.”

Lyme disease is a vector-borne illness transmitted to humans through a tick bite. Symptoms can include fever, fatigue, joint pain and more serious nervous system complications.

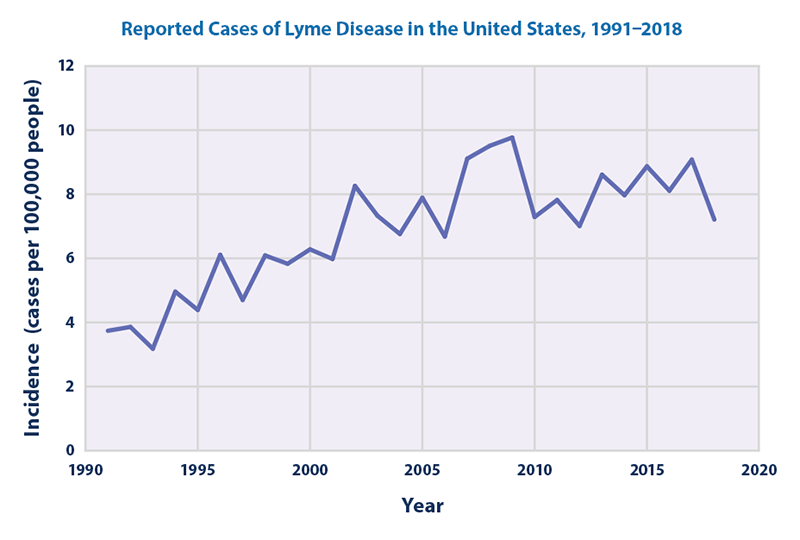

The incidence of Lyme in the U.S. has nearly doubled since the early 1990s, with about 35,000 cases reported annually to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But recent research suggests as many as 476,000 people are treated for Lyme each year in the U.S.

In the past decade, more studies have been published about both the diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease. Nevertheless, Lyme experts say funding to better understand the condition is still lacking and patients like Annis still struggle to get help.

Advocates say it’s time for that to change, especially with predictions that climate change could bring more cases to more places across the U.S.

“Before I got diagnosed with Lyme, they told me that I had complex PTSD and that all of my pain was psychosomatic,” Annis said, “which means basically, ‘It’s in your head.’”

A difficult diagnosis

Lyme is typically diagnosed with a two-step antibody test from a blood sample, and most cases can be treated with two weeks of antibiotics. A bullseye-shaped rash, called erythema migrans, is a telltale sign doctors look for to determine whether a patient should be tested, but it often doesn’t appear and patients may test negative if antibodies haven’t developed, according to the CDC.

LymeDisease.org, a California nonprofit, says delayed antibody development, immune system suppression and different Lyme strains might also lead to false negatives.

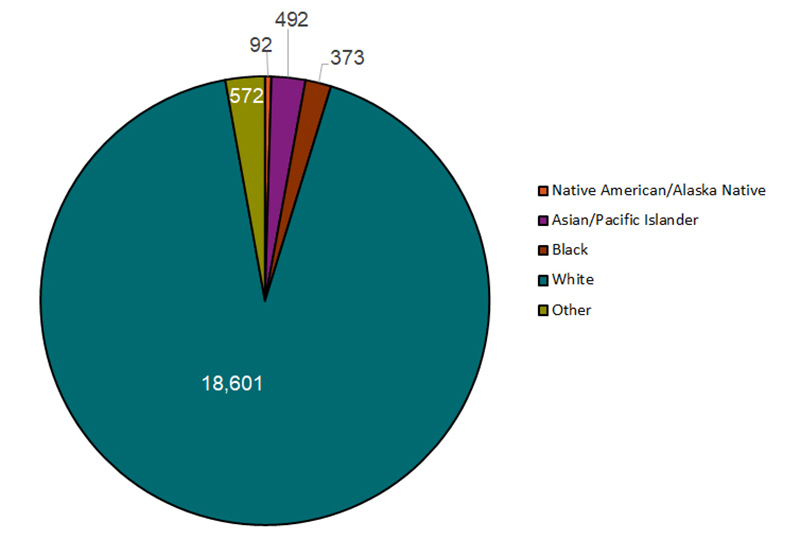

Getting diagnosed and treated is even more grueling for patients of color. Available CDC data shows 92% of Lyme patients for which race or ethnicity was reported in 2019 were white.

Obstacles to an accurate diagnosis include identifying the bullseye rash on darker complexions and the lack of “Lyme-literate” doctors of color, said Dr. Crystal Barnwell, a Lyme specialist in Decatur, Georgia.

“When you start with a disease that requires 20 office visits (to get a proper diagnosis), you cut any brown and black bodies out of the conversation just getting started,” Barnwell said.

Reported confirmed and probable Lyme disease cases by race and ethnicity, 2019. Data on race was available for 58% of 34,945 cases. (Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Beyond difficulties in diagnosing Lyme, what makes the disease so controversial are questions about whether a chronic form exists and, if so, how best to treat it.

Some advocates say parallels can be drawn between Lyme and long-haul COVID, which initially was dismissed by some experts even as more and more cases were reported.

The CDC calls long-term Lyme symptoms a product of post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome, in which some symptoms persist for months, and says there is no proven treatment. Other experts note that symptoms of chronic fatigue and pain are common, and that patients with symptoms attributed to chronic Lyme may have other conditions.

But patients like Annis believe they have a chronic form of Lyme.

The controversy in treating chronic Lyme is when the two-step antibody test no longer detects Lyme or never even detected it initially, but a patient’s symptoms persist or worsen.

“We’re the lepers of society,” Annis said.

Lorraine Johnson, CEO of LymeDisease.org, serves as principal investigator for the patient registry and research platform MyLymeData, launched in 2015. With over 15,000 patients registered, the site collects data on access to care, quality of life, symptoms, diagnosis and treatments.

Seven percent of registered patients report they are well, and 64% say they have chronic Lyme.

In other words, Johnson said, there is no average Lyme patient. “There are people who respond really well to treatment,” she said, “(and) others who aren’t responding well.”

Johnson hopes the conversation around long-haul COVID-19 will help change the narrative around persistent forms of Lyme.

“People don’t know exactly how (long-haul COVID) works. They don’t know exactly how many people get better. But they recognize that it exists,” she said. “Whereas in Lyme disease, we’ve had to really struggle with the fact that it exists – that there are people who have persistent symptoms for decades.”

The struggle for support

Annis spent years trying to convince not only doctors but members of her own family that her symptoms were real. She felt like she had to somehow prove that Lyme was the cause of her problems, because she couldn’t pinpoint exactly where her disease originated.

“You are discriminated against and gaslit before you even open your mouth,” she said.

That fight for validation isn’t uncommon. About 70% of patients reporting to MyLymeData experience a delayed diagnosis, and an “extraordinary amount” of people are misdiagnosed for years, especially outside of areas where Lyme disease is common, Johnson said.

Historically, Lyme transmission has been high in New England, the mid-Atlantic and a portion of the Upper Midwest – regions where the disease is considered endemic and the primary vector, the blacklegged tick or deer tick, is prevalent.

However, the Environmental Protection Agency and independent researchers note the disease is spreading, in part because rising temperatures brought on by climate change have expanded the habitat in which deer ticks can thrive.

For example, research shows Lyme is on the rise in parts of Canada, and one study published in the Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology predicts the number of Lyme cases in the U.S. will increase by more than 20% in coming years.

Johnson said living in Arizona and other states considered low incidence can contribute to misdiagnoses because many doctors won’t even consider the possibility of Lyme when a patient presents with symptoms.

“To live in one of the states that the CDC doesn’t call a high incidence state, you’re in real trouble,” she said. “It’s really an insidious cycle of awareness and reporting.”

Advocates for better awareness of the disease believe debate over Lyme’s prevalence and its longer-term effects have affected the amount of funding going toward research.

In 2020, about $40 million was spent on Lyme research funded by the National Institutes of Health. All vector-borne diseases, including malaria, dengue fever and West Nile virus, received $731 million in research funding.

“The numbers (of Lyme cases) are exploding upwards … and the funding is not reflecting that need at this point in time,” said Dr. Raj Patel, who treats chronic Lyme through an integrative approach in the Bay Area.

Costly treatment

While funding for research lags, the cost of treatment can be exorbitant.

Before seeking treatment in Mexico, Annis said she was spending $1,000 a month just on herbal supplements. Since she left her job in digital marketing several years ago, she has had no health insurance or income. Annis said she’s lucky her family has supported her financially – without them, she’d likely be in a homeless shelter.

Now working with doctors in Puerto Vallarta who specialize in Lyme, parasites and mold, she has tried a multitude of treatments, including two to four IVs a week for vitamins, minerals and detoxing.

Annis, who’s in her first year of treatment, said it will take at least two to four years to get better – an enormous expense when considering how long it took to get diagnosed in the first place. She said her family has spent at least $50,000 on her treatment.

“Being a Lyme patient is so expensive, and there’s always 100,000 more dollars you can be spending,” she said.

The high costs of treatment come from a combination of lack of insurance coverage and the need for more treatment when symptoms persist. Fifty percent of patients from MyLymeData report that their doctors don’t accept insurance.

Johnson cites exclusion of doctors from insurance networks and longer patient visits as possible reasons for having to pay out of pocket.

Patel doesn’t take insurance but provides a superbill that patients can submit to their insurance companies. He says that most insurance doesn’t cover Lyme treatment beyond antibiotics because the condition is time-intensive.

Lyme doctors, patients and advocates agree that thorough, widespread education about Lyme and more accurate testing for early cases are the keys to avoiding misdiagnosis and lowering the cost of treatment.

For now, patients like Annis find most of their support in online groups where fellow Lyme patients share studies, news stories and personal treatment recommendations. Her own private group documenting her treatment journey, Spinning Circles With Christy, has almost 700 followers. Annis shares life updates about new symptoms, treatment outcomes, and celebratory moments, while others post their own experiences in support.

“I don’t know where I would be without these Facebook groups,” she said. “That’s where you learn everything.”

In the face of the innumerable challenges and stigmas associated with Lyme disease, Barnwell, the Georgia specialist, says she has hope about the future conversation surrounding the disease.

“There are a lot of brilliant young people who have been injured by Lyme growing up who do have an opinion about this topic and who are coming of age,” she said. “They will participate in this conversation until it morphs into a better conversation, something better than what we currently have.”