WASHINGTON – Both sides in the election law debate agree on at least one thing: The Supreme Court’s expected ruling Thursday in an Arizona election law case will be felt well beyond the state’s borders.

At issue in Brnovich v. DNC are Arizona’s bans on ballot collecting and its restrictions on out-of-precinct voting, which were voided by a lower court in 2020 that said the policies limit minority voters’ access to the ballot box.

The high court’s decision in the case will affect Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which advocates say is the only remaining defense against voter suppression after the Supreme Court “gutted” Section 5 of the same act in 2013.

“The key question is, will the court continue to gut the Voting Rights Act or will they affirm this critical federal law that safeguards our Constitution’s guarantee of equal voting rights?” asked David Gans, director of the Constitutional Accountability Center’s Human Rights, Civil Rights & Citizenship Program.

But Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich defended the state’s policies in March arguments before the high court as race-neutral “common-sense and commonplace” protections of election integrity. Supporters accused the lower court of overstepping its authority and stripping states of their right to regulate elections.

“We’re hopeful that the court will interpret the Voting Rights Act to make clear that state legislators have the right to set fair, clear rules ahead of an election and that federal judges are obligated to respect those rules when elections take place,” said Daniel Suhr, senior attorney with the Liberty Justice Center.

The case began in 2016 when the Democratic National Committee and others sued Arizona over the two policies, charging that they disproportionately affect the ability of minority voters to cast a ballot.

The “ballot-harvesting” law, approved by state lawmakers in 2016, made it a felony for anyone other than a voter, a voter’s family member or a letter carrier to collect and turn in the voter’s ballot. Critics of ballot collection say it is ripe for fraud and voter intimidation, but others say it is the only way for many people in underserved communities to vote.

“That (ballot-harvesting ban) has a very strongly negative impact on people on reservations and Latino people who have bad mail service in Arizona,” said Paul Smith, vice president of the Campaign Legal Center.

The out-of-precinct rule requires state election officials to discard the entire ballot of anyone who votes in the wrong precinct – even if the ballot is processed by the same office as the voter’s assigned precinct and races on it are not affected by precinct, as with statewide races.

Smith said “many more people who have that problem are Black, Latino and Native American.” Critics said those communities are most likely to see precincts shift or close, and less likely to have transportation for a last-minute change.

But Jason Snead, executive director for the Honest Elections Project, said the problem is not as widespread as critics claim.

“In the 2016 general election, out of 2,600,000 ballots cast, only 3,970 were in the wrong precinct,” Snead said. “That’s 0.15%.”

A federal district court agreed with Snead and others, ruling in 2018 that the policies did not unfairly burden minority voters. A three-judge panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed.

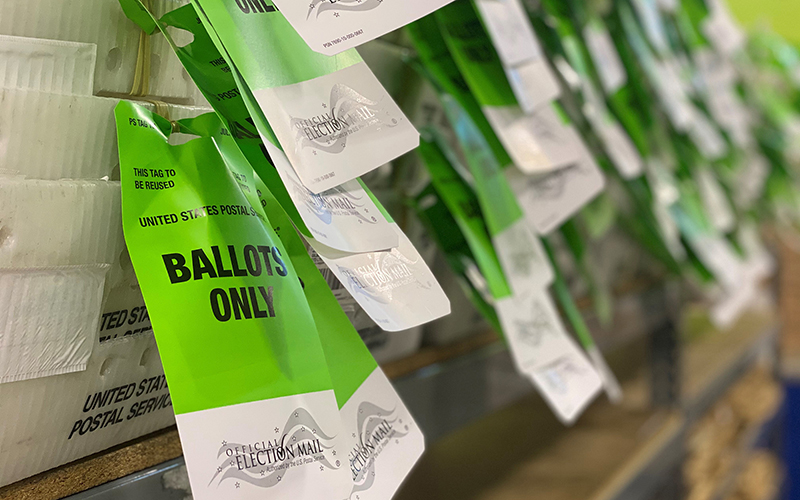

The Supreme Court has two cases left to decide, with Thursday set as the last scheduled day for the term: Brnovich v. DNC and a challenge to a California law requiring disclosure of financial donors to nonprofits. (File photo by Vandana Ravikumar/Cronkite News)

But the full 9th Circuit voted to review the panel’s finding, and a sharply divided court reversed the lower courts last year. The majority wrote that the Arizona policies “have a discriminatory impact on American Indian, Hispanic and African American voters in Arizona.”

The court said that violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits voting practices or procedures that discriminate against minority groups – an assertion challenged by dissenting judges who said the majority “simply failed to show” that the policies burdened minority voters.

Critics said that instead of supporting “clear rules” made by elected officials, the 9th Circuit decision supports “constantly evolving” rules made by judges.

“The 9th Circuit, once again, is exercising raw judicial power in a way that is unanchored to and exceeds the actual text of the statute at issue,” Suhr said.

Chris Kieser, an attorney at the Pacific Legal Foundation, agreed that the Arizona policies do not unfairly burden any one group of voters.

“Under the 9th Circuit’s view, any voting regulation that happens to produce a statistically disparate impact by race is viewed with skepticism, even if all voters have an opportunity to vote in several ways,” Kieser said.

But advocates worry that any weakening of Section 2 will further harm voting rights safeguards after the Supreme Court’s 2013 ruling in Shelby County v. Holder.

Gans said that decision “annulled one of the most important parts of the Voting Rights Act,” Section 5. That section required that certain states get federal approval to enact any changes to their voting laws to make sure they did not deny the right to vote based on race, color, or membership in a language minority group.

Arizona was one of the states that had to get federal “preclearance” under Section 5, before the court rejected that requirement in Shelby County.

When the court voided Section 5, Smith said the rationalization was that “you still have Section 2, so there’s still good strong remedies against discriminatory voting rules.”

“It would be really unfortunate if the court goes ahead and makes Section 2 no longer available and useful as well,” he said. “We’ll have to wait and see.”

Most experts believe the high court will side with Arizona. The question is whether the court will issue a ruling narrowly tailored to the facts of the Arizona case or whether its decision will set a clear standard for when and how Section 2 can be applied.

Kieser hopes the court rules that “socioeconomic disparities alone do not trigger a Section 2 violation.” That would give states “more leeway in pursuing voting regulations, but it would obviously not allow states to discriminate on the basis of race in election law.”

The ruling comes as lawmakers across the country have proposed hundreds of election laws – to protect election integrity or to restrict voting rights, depending on who’s talking.

Snead said that if the court rules that the Arizona policies are discriminatory, “that will open up basically every election law in the country” to debate.

But Gans worries that if the court upholds the Arizona policies, it would “give wide authority to state legislatures to impose arbitrary and discriminatory regulations that make it harder for voters in communities of color to exercise their fundamental right to vote.”

“It’s about these Arizona laws, but it comes against this backdrop of a concerted effort to roll back voting rights in a lot of different states in the country,” Gans said.