WASHINGTON – Patrick Caserta hopes no one has to go through what he and his wife, Teri, went through in 2018 when their son died by suicide while serving in the Navy.

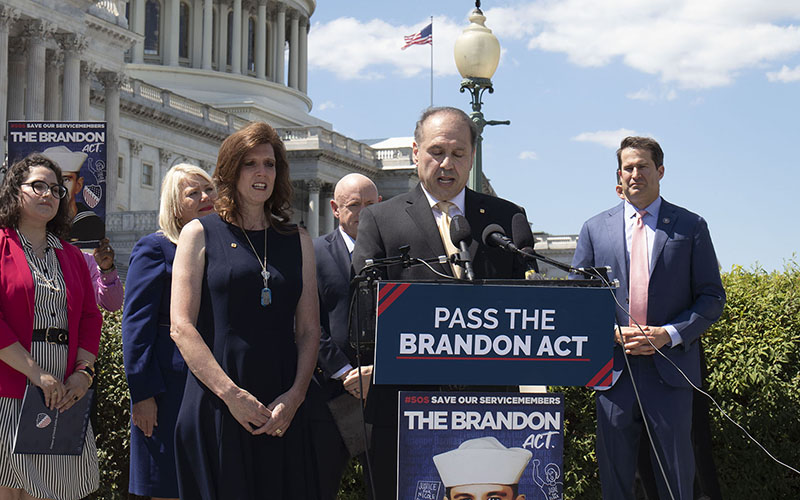

That’s why the Peoria parents were in Washington Wednesday for the introduction of the Brandon Act, a bill that would provide service members confidential access to mental health care without fear of rebuke or retaliation.

This is the second try for the bill, named in memory of Brandon Caserta, that was introduced last year but failed to get a hearing.

“I’m sending an SOS to the American people right here right now,” said Patrick Caserta, during a news conference at the Capitol. “The Brandon Act is for our current and future service members and to prevent others from having to go through what Brandon and we have and continue to this day.”

The parents were joined by House and Senate members who support the bipartisan bill that they said would “help solve the problem” by providing an outlet for service members to self-report mental health issues without notifying the chain of command.

“The Brandon Act would show men and women in uniform that they can admit they’re struggling with mental health issues and ask for help,” said Sen. Mark Kelly, D-Ariz., a Navy veteran and supporter of the bill.

Brandon Caserta’s parents said that had there been mental health help like that proposed in the Brandon Act available in 2018, it might have saved their son’s life. (Photo courtesy the Caserta family)

The bill would let soldiers and sailors identify a safe phrase that they could use to let superior officers know when they are in distress, and it would require that the officers refer the service member for a mental health evaluation once the phrase is invoked. Kelly said in a prepared statement that it could be something as simple as “Brandon Act,” which Patrick Caserta called the equivalent of a “verbal 911” call for help.

Brandon did not have that option on June 25, 2018, when he took his life while stationed in Norfolk, Virginia.

He enlisted at age 17 with dreams of becoming a Navy SEAL. But he was forced out of SEAL training in May 2017 after breaking his leg – an injury his parents say was not originally diagnosed and not properly treated.

He was later reassigned to units where his parents said he was harassed and belittled by his petty officer for not making the SEALs, saw his efforts to train for other specializations subverted by his superiors and was continually mocked and bullied.

After a year of such treatment, he wrote a suicide note to his parents in which he said he “felt empty and useless to myself.”

“I want this depression to be over and, let’s be honest, it was never going to go away,” he wrote, specifying that he did not want a military funeral.

Sindy Benavides, CEO for the League of United Latin American Citizens, said at Wednesday news conference that the Brandon Act is a “bill that we all need as families,”

“We believe Brandon would’ve been saved if he would’ve been able to get the help he needed,” said Benavides, whose organization is hosting a memorial next week on the anniversary of Brandon’s death.

“Tragically the system failed Brandon and others,” Kelly said. “We must ensure that those who risk their lives for our country have access to mental health care when needed.”

The bill comes as military suicides continue to climb, with 99 active-duty deaths in the last three months of 2020 alone, according to the latest Pentagon reports, up from the 75 reported in the quarter when Brandon died.

The report also said active-duty suicides have increased every year since 2014, with the 377 deaths of 2020 being the most since the Pentagon started collecting suicide data in 2012. Those numbers are why supporters say the Brandon Act is needed now more than ever.

Rep. Debbie Lesko, R-Peoria, acknowledged that the bill failed in the last Congress, but looked at the Casertas on Wednesday and assured them, “We’re going to do it.”

Patrick Caserta said the act “will save our service members’ lives.”

“It’s a verbal 911 but more importantly, it keeps our service members alive while they navigate through all the obstacles and roadblocks that are put in front of them,” he said.

Active-duty members and their families face the issue of asking for help every day, Patrick Caserta said, calling the struggle for access to mental health support “a matter of life and death.”

“People are dying, there’s one to two active-duty suicides every day, and we have to do something or this will keep happening,” he said.