PHOENIX – As cases of COVID-19 continue to surge in Arizona and the rest of the nation, the state’s three public universities are wrangling their approaches to the pandemic in similar but separate ways.

Arizona State University developed a saliva-based test and aims to monitor the spread through frequent mass testing.

The University of Arizona, unlike its counterparts, invested in a wastewater test to monitor the spread in highly populated places on campus and suggested a schoolwide shelter-in-place initiative.

Northern Arizona University, the smallest of the three, has changed the least. It adopted ASU’s saliva test and shares UArizona’s system for contact tracing, but it has been the most lenient with in-person education, offering classes with fewer than 45 students.

As the end of the semester nears, holiday travel ramps up and the pandemic reaches a critical juncture, college campuses and their thousands of students are being further scrutinized.

All three Arizona universities will end all in-person classes after the Thanksgiving holiday and recommended students and faculty get tested before any holiday travel and before they return in the spring.

As of Tuesday, Nov. 24, the Arizona Department of Health reported 4,544 new cases with a percent positive rate of 9.9%. In Maricopa County, which includes four of ASU’s campuses, the positivity rate exceeded the state average by nearly 1%.

Nationally, there have been more than 12 million cases of COVID-19 and more than 1 million cases in the past seven days alone, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Johns Hopkins University reports a national seven-day percent positive rate of 9.6%.

“They’re using their strengths,” Will Humble, executive director for the Arizona Public Health Association, said of the slight differences in approaches among Arizona campuses. “But in the end it will be really interesting to see (when) we can look back at the three universities and compare their outcomes and we’ll be able to tell which approaches were most effective.”

Humble said it is too early to draw definitive conclusions, but he praised each university for acting fast.

No federal, state or college standards are in place for mitigating the novel coronavirus or documenting its spread, leaving university leaders to come up with their own plans. These are some of the pandemic protocols that Arizona’s public universities have developed, with any variation in each school’s approach based on factors such as resources, enrollment and community involvement.

“It’s really hard,” said McKenna Lane, a freshman living in the on-campus dormitory for Barrett, the Honors College at ASU. “I don’t think it’s OK to do whatever you want, but I also think some college students are struggling a lot.”

As the end of the fall semester nears, holiday travel ramps up and the coronavirus continues unchecked, health experts are focusing on college campuses and their thousands of students. (Photo by Allie Barton/Cronkite News)

The new campus normal

Since resuming classes in the fall, all three universities have mandated mask wearing and other guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and required daily health checks. They also urge students and staff to stay home if they feel ill and require students to socially distance themselves from others.

NAU, similar to the other schools, rearranged classrooms to accommodate social distancing and were equipped with disinfectant wipes. Classes requiring field work, clinical work, labs, simulation, performance, internships and practicums remained in-person throughout the semester at NAU, said Heidi Toth, assistant director of communications for the school.

Toth added that classrooms were arranged to accommodate social distancing and cleaned in a “stringent and timely” manner, as most students opted for a hybrid form of learning – a combination of online and in-person schooling

At UArizona – after an outbreak in late September where 880 students and faculty tested positive for the virus in seven days led to stringent in-person restrictions – leaders have loosened the reins. Now, classes with fewer than 50 students may meet in person.

“Our goal in the spring semester – if there was no surge and everything stayed stable – going up even more and opening up (in-person classes) to 100 students,” said former U.S. surgeon general Richard Carmona, a distinguished professor at the UArizona who is tasked with spearheading the schools’ COVID response initiative. “But the likelihood of us being able to open at that level is slimmer and slimmer every day as we continue to see a surge.”

ASU, which already is known for its robust online learning programs, leaned further into a hybrid classroom model put into place in the spring where students can choose to be in-person or work remotely “live.”

“In terms of how other universities are faring, ASU has really been thoughtful and strong, and in a good place,” said Teri Pipe, a professor at ASU’s Edson College of Nursing and the university’s “chief well-being officer.”

Pipe said the adjustment was made easier by technical support and resources from the school setting up ASU Sync – the school’s way of holding class in real time, virtually.

UArizona and NAU have adopted similar programs for teaching classes remotely and holding students accountable for a regular class schedule.

“I don’t have any complaints,” Pipe said, adding, “I think students might have a different view of that.”

In continuing degree programs like graduate degrees and Ph.D. students, she found some students in early stages chose to defer their schooling, attempting to outlast the virus and return once school resumes in person.

Still, enrollment hasn’t suffered drastically at any of the institutions from 2019 to 2020, although the changes from fall 2020 to spring 2021 are unclear.

Each school also requires a daily health check to keep track of the number of students on campus and as a reminder for each student to “check in” on how they are feeling that day.

ASU, one of the largest universities in the nation, distributed resource kits as part of its Community of Care program to students, faculty and staff to promote health and safety on and off campus. Each care package has reusable face masks, a thermometer and hand sanitizer.

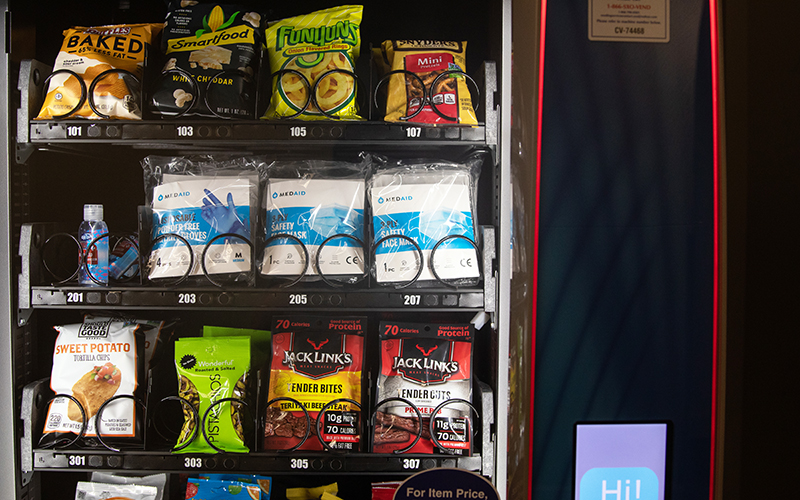

Sanitizer bottles and masks nestle next to snacks in a vending machine on the Arizona State University campus. (Photo by Allie Barton/Cronkite News)

The domino effect of off-campus behavior

Despite new classroom accommodations and learning methods, challenges regulating off campus behavior pose the possibility of new outbreaks on campus.

“Off campus behavior has a direct impact on the success of the whole reentry program, that’s why it’s so key to have a partnership between (the school) and the city,” Humble said, adding that he found UArizona’s efforts to cooperate with the surrounding community to be the most effective.

Carmona said UArizona “needed to form a partnership with the mayor, the city, and the board of supervisors because we’re all sharing 1.1 million people in this geographic area.” The university, he said, “let them know what’s happening and we share tested results in the whole community because the university is not an ecosystem unto itself.”

Humble said ASU President Michael Crow has tried to replicate the community relationships that UArizona fostered but has struggled to establish the same cooperation.

ASU’s provost, Mark Searle in an announcement on Nov. 7, named students’ off-campus behavior as an issue. But one student said those guidelines are inconsistent and vague.

“I think a lot of it is off campus, but there are ways on campus to spread it really easily,” said Lane, who remained in her dorm for the semester, even with a schedule packed with online classes.

Lane said she felt well versed on the school’s requirements for on-campus living but school leaders were offering little help – beyond wearing a mask and keeping distance – when it came to ASU’s COVID-related code of conduct.

“There’s a lot of different ways that they try to handle it, and that makes it confusing because you don’t know what to expect,” Lane said.

Pursuing personal responsibility for coronavirus prevention

If she got the virus, Lane said she would expect a phone call notifying her of her test results, but wouldn’t know the next steps taken by the school. And contact tracing is, unofficially, a burden born by the student, she said.

The school has discussed practices for contact tracing. Lane said she has been in close proximity to other students who tested positive and was not contacted by the school.

NAU and UArizona encourage students to do their own contact tracing to limit exposure to the coronavirus. They recommend a smartphone app called COVID Watch Arizona, released in partnership with the Arizona health department, to monitor contact tracing in the community.

The impact of COVID-19 on campus life has been profound.

Lane, an 18-year-old seeking new friendships and the “big college” experience, has yet to attend an ASU home football game, although that’s what she is looking forward to most in a post-COVID world.

Lane said a university with more than 74,000 students feels “just like high school,” inside the bubble of her dorm room. Largely limited to her roommates, those on her floor, passersby at the gym, library, or dining hall, Lane doubts she sees more than 50 people in a day.

“It feels like you’re like missing out all the time and everyone keeps reminding you,” Lane said. “But I had to learn to be OK with missing out on hanging out with people … and I feel like a lot of people are going through that for different reasons.”

Lane said she didn’t know of anyone who was asked to leave housing or school for violating new COVID procedures. She said many people still do, adding that some of her peers pursue active social lives.

“But if you follow the rules to a T, I think you would be really, really lonely,” Lane said. “It’s just difficult to determine how risky you want to be, and I feel like it changes almost every week.”

What the positive number of cases shows

In September, ASU faced criticism from students, on-campus organizations and anonymous watchdog accounts on social media for its changing methods of calculating the rate of positive tests it makes public on its website, which the critics said gave the appearance of fewer cases on campus than the reality.

Since the backlash, ASU updates its online COVID management page with more information, including the number of positive cases in comparison to the previous week, how many tests came from random selection, the number of students on campus, and a general idea of the campus where cases are located.

UArizona and ASU also give regular updates to the campus community and the public, with Dr. Joshua LaBaer, executive director of ASU’s Biodesign Institute, providing updates and advice.

The UArizona’s positive infection rate has stayed low since its shelter-in-place initiative, resting around 2% on Nov. 24 while the school manages 30 cases among students, faculty and staff.

That compares to 65 student cases as of Nov. 20 at NAU and the 408 current active cases at ASU.

Cases for all three schools are on the rise, similar to statewide and national trends.

Arizona’s three public universities have made testing a cornerstone of their approach to mitigating the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. (Photo by Allie Barton/Cronkite News)

Frequent testing turns into a routine

Lane left her on-campus dorm with enough time to quarantine for 14 days at home in Arizona before Thanksgiving. She lives and works on campus and gets tested about three times a week.

ASU offers free saliva-based tests, developed and overseen by the Biodesign Institute, as often as people want to take them.

As of Monday, the school has collected 136,177 coronavirus tests since Aug. 1. Although there is no regulation on how universities address the pandemic, some schools made rigorous testing their primary defense.

NAU adopted ASU’s saliva test soon after it was developed and has administered more than 30,000 tests in collaboration with Coconino County and the state health department. ASU and NAU offer tests free to the public and randomly tests students, faculty and staff.

UArizona, falling between the other two in both school size and volume of tests with 83,921 tests since Nov. 23, is set to implement its own saliva-based test on Dec. 7.

Until then, UArizona will continue administering its two diagnostic tests by using a nasal swab, and also offers an antibody test. One diagnostic test yields results in about 30 minutes.

Humble said faster results lead to faster decisions, which is key in this pandemic.

He added that a saliva test like ASU’s may be more accurate but take longer for an individual to receive results, at least 24 hours. UArizona’s rapid response test quickly makes the school aware of any changes with coronavirus cases.

UArizona invested in a wastewater test, now a common practice, according to the CDC, to identify and monitor changes in high-spreading areas through sewage water as a form of virus surveillance.

“Waste often tells you the health of a community, if you backtrack it,” Carmona said, adding that UArizona collaborated with experts to organize and execute the first-ever plan to test wastewater for COVID-19.

UArizona quickly found a positive result at one of the dormitories after testing wastewater and immediately tested all 311 students in the building until two asymptomatic cases were identified and isolated, Carmona said.

“Our goal is to test everybody every day,” Carmona said. “We don’t have the scalability yet. (But) we are pushing as hard as we can.”