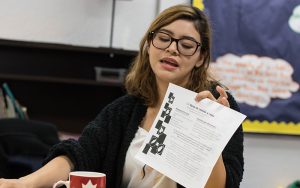

Cynthia Aragon, executive assistant and outreach coordinator for Phoenix nonprofit Helping Families in Need, visits schools in the Roosevelt district to help families apply for public benefits. (Photo by Daja Henry/Special for Cronkite News)

Irene Cervantes brought her infant daughter to a presentation at Southwest School that included information about enrolling in public benefits. (Photo by Daja Henry/Special for Cronkite News)

As Southwest School’s parent coordinator, Sharon Rideau gets to know her students’ families and their struggles, including problems with immigration. (Photo by Daja Henry/Special for Cronkite News)

Principal Juan Sierra talks with Beatríz Martínez Rodríguez about the mother’s concerns at Southwest School in Phoenix. (Photo by Daja Henry/Special for Cronkite News)

Mothers, from left, Ana Sanchez, Armida Rodriguez and Olivia González Sierra were among those at a presentation that included a Q&A about the public charge rule. (Photo by Daja Henry/Special for Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Cynthia Aragon stands in an elementary school library in south Phoenix, facing a group of parents not so different from her own – 11 Latinas, some in the country legally and some not.

One mother is talking about her third grader, who recently was diagnosed with autism. He struggles to speak and is falling behind his classmates. Occupational therapy would help, and is accessible through public benefits, but she is too afraid to enroll him.

Another mother has a kindergartner born with her tongue attached to the base of her mouth – a common condition easily fixed with surgery. But the family can’t afford the procedure and is scared to enroll the girl in Arizona’s Medicaid program.

Aragon’s job is to help qualified families make use of public benefits like food stamps, cash assistance and the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, the state’s Medicaid program. A few mornings each week, she makes presentations to parents in Phoenix’s Roosevelt School District, where nearly 97% of students are minorities, most of them Hispanic.

The 25-year-old has been at this effort for more than six years. Never before has her job been so difficult.

“They have a lot of questions … and fear,” Aragon said, “because they’re scared of the unknown.”

For months now, advocates nationwide have been sounding the alarm over a Trump administration change to the so-called “public charge” rule – guidelines used to determine whether immigrants seeking legal status are likely to be a burden on the country’s resources.

The update allows immigration officers to consider applicants’ use of certain public benefits, including Medicaid, in deciding to grant green cards, visas and changes in residency.

The U.S. Supreme Court last month voted 5-4 to lift lower court injunctions that had blocked the rule, allowing it to take effect while other court challenges play out. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services will implement the changes beginning Feb. 24, except in Illinois, where an injunction remains in place.

Those who support the change say it encourages self-sufficiency.

The changes, said Ken Cuccinelli, acting deputy secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, “will … promote immigrant success and protect American taxpayers.”

However, immigration lawyers and activists argue the rule change is causing fear, confusion and mass withdrawal from public benefits, leaving many without health care.

Statistics on health insurance enrollment seem to support those concerns.

In Arizona, 106,000 fewer Hispanics were enrolled in AHCCCS in January 2020 than in July 2018, according to state statistics, despite an increase in overall enrollment. Similar trends are found in Medicaid data in Florida and California – collectively home to 33% of the nation’s Hispanics.

Since the new rule was leaked in March 2018, Aragon and other health advisers have struggled to persuade people to use the benefits they or their children may desperately need – even if they’re unlikely to be affected by the changes.

Aragon understands the fear. She hears it in conversations around her family’s dinner table.

Aragon’s half siblings, both U.S. citizens, are among those who have been removed from public assistance rolls. Her father, Elias Aragon, took America, 13, and Ali, 8, out of KidsCare – a health insurance program for children in low-income families – fearing their participation would hurt their mother’s application to become a legal permanent resident.

KidsCare isn’t affected by the rule change, according to Aragon, but she was unable to convince her father, who added the children to his private plan. In the wake of this expense, the family visits food banks to make ends meet.

“(He) disenrolled my siblings because of the fear of the unknown,” Aragon said, though she knows her family will survive. “The community is very resilient. My dad’s been through worse than not having to enroll in benefits.”

Laura Corrales is one of more than a dozen mothers who gathered at Southwest School in Phoenix to talk about their children’s special needs. (Photo by Daja Henry/Special for Cronkite News)

Aragon is the epitome of the American immigrant’s dream. Her father came here in the 1990s from Guatemala and earned his green card. He now owns a home and installs drywall for a living.

Aragon won a scholarship to Arizona State University and worked her way through college.

As a freshman, Aragon landed a part-time job as an outreach coordinator with Helping Families in Need, a Phoenix organization that helps educate families about health services.

Six years and several promotions later, she works as an executive assistant, grant writer and school outreach coordinator for the group.

She routinely deals with parents with the same dream for their children: to make it in America.

But since the public charge changes were announced, her clients aren’t taking any chances. Some would rather forgo all benefits, even those unaffected by the new guidelines.

“There’s a lot of misinformation out there,” Aragon said. “The way it was even defined, it was put out there to be very confusing, even for professionals.”

Public charge does not apply to all immigrants but rather to those applying for green cards (legal permanent residency) or for visas to enter the country. Immigrant advocates note that health and food benefits received by the child of a green card applicant do not count against the adult applicant. The rule also does not affect those who already have green cards who may be applying for renewal or citizenship.

Southwest School Principal Juan Sierra is trained in linguistics and anthropology. He is talking with mothers about various concerns involving their children. (Photo by Daja Henry/Special for Cronkite News)

Despite the guidelines, conflicting and often exaggerated interpretations of the rule have spread among immigrants.

“We’re kind of reliving SB 1070,” said health care advocate Claudia Maldonado, referring to the Arizona immigration law that garnered national attention. Until it was gutted, the so-called “show me your papers” law allowed officers to investigate any “reasonable suspicion” that a person was in the country illegally.

“It’s like reliving the fear, the chilling effect and the suspicion,” she said.

Maldonado manages health care advisers at Keogh Health Connection, a Phoenix organization offering free benefit enrollment assistance. She remembers the exact moment last August when the final public charge changes were publicly announced.

Maldonado and the rest of the field staff stopped working and stared at each other in disbelief, she recalled. That same day, people began calling and coming into the center asking to withdraw themselves and their children from benefits.

Livbier Pearson, who also works at Keogh, remembers a mother of three children with chronic health conditions who immediately removed them from KidsCare. Now, Pearson said, that mother spends 60% of her paycheck on her children’s private health insurance.

Recalling her meeting with the mother, Pearson said, “When you see her face, her agony, it just hits you. It’s hard.”

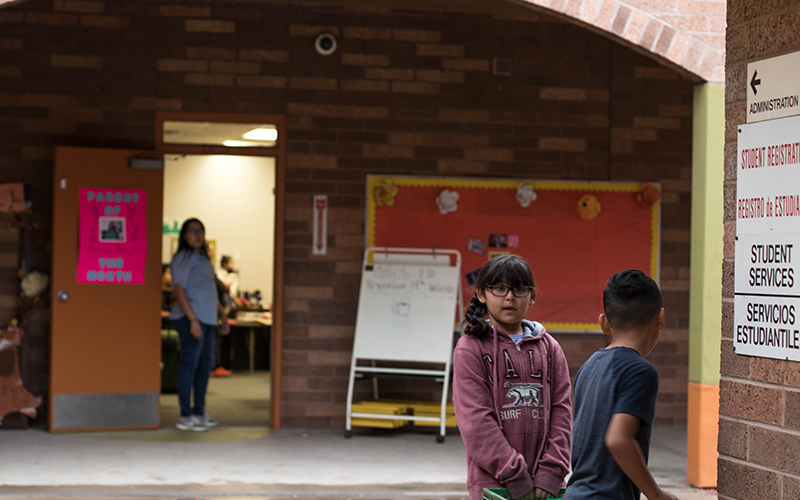

Southwest School, an elementary school in south Phoenix’s Roosevelt School District, serves a majority Hispanic/Latino population. (Photo by Daja Henry/Special for Cronkite News)

There has been no consensus on how many people the rule changes could affect; the Department of Homeland Security predicts nearly 77,000 people may drop out of Medicaid as a result. Others argue that number is low.

Leighton Ku, director of the Center for Health Policy Research at George Washington University, conducted an analysis and found that 1 million to 3.1 million people would forgo Medicaid in response to the rule change.

Ku said understanding Medicaid enrollment is tricky, because not all states collect or report data the same way. But a sampling of statistics from different states suggests that Arizona’s lower enrollment numbers for Hispanics may be part of a bigger trend.

According to data from the California Health and Human Services Agency, in the first quarter of 2018, there were 225,105 Medicaid applicants in California who identified as Hispanic. In the second quarter of 2019, that fell to 163,175.

Data from the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration tells a similar story. From January 2018 to December 2019, Medicaid enrollment dropped more than 5% statewide and 11% in Miami-Dade County, which is majority Latino.

Steven Camarota, director of research for the Center for Immigration Studies, supports the rule change but acknowledges misinformation and fear may be causing a drop in health insurance enrollment. He predicts that won’t last.

“If there is a chilling effect, I expect it to be temporary. Immigrants are smart. They figure stuff out pretty quickly,” said Camarota, whose group favors tougher restrictions on immigration.

Ku said although the true scope of the impact may be impossible to predict, there is no doubt that there already have been, and likely will be more, negative consequences.

Cynthia Aragon, executive assistant and outreach coordinator for Phoenix nonprofit Helping Families in Need, talks with mothers about such resources as health care and food banks. (Photo by Daja Henry/Special for Cronkite News)

“Clearly, it is the case that people will lose benefits because of this. They will suffer harm because they’re not going to be able to get the care that they need,” he said.

In Phoenix, after meeting with the 11 moms at V.H. Lassen Elementary School, Aragon walked to another classroom with Lorenia Cates, the school’s family engagement coordinator. Behind closed doors, the two talked about specific cases. Cates has no shortage of stories about families afraid to get their children the health care they need.

“They’re afraid they’ll lose everything,” Cates said.

Data suggests that for many immigrant families, withdrawing from or declining to enroll in public health care benefits means being uninsured entirely.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the percentage of foreign-born noncitizens without health insurance rose 2.3%, or by more than 500,000 people, from 2017 to 2018. In 2018, there were 1.1 million more uninsured Hispanics, both citizens and noncitizens, than in 2017.

Sandra Mayol-Kreiser, a clinical professor at Arizona State University’s College of Health Solutions, said a lack of adequate health care can be particularly harmful for children at critical points in their development. It can cause issues that manifest years into the future and affect education outcomes.

Beyond that, she said, a greater childhood uninsured rate can have societal consequences.

“If you have people whose kids are not getting the vaccinations they need at a certain time, you have patient zero that has a disease that is contagious,” Mayol-Kreiser said. “It could cost society, because we all work together.”

Maricopa County has one of the nation’s highest uninsured rates for children. Lack of adequate health care can have lasting effects on children, said Sandra Mayol-Kreiser, a clinical professor at Arizona State University’s College of Health Solutions. (Photo by Daja Henry/Special for Cronkite News)

Arizona has the third-highest rate of uninsured children in the U.S., and Maricopa County has the third-highest number of uninsured kids in the nation – some 92,000 children, according to a report by Georgetown University.

As she continues on in her work, Aragon has successfully persuaded about half the families she’s met with to use the benefits available to them.

“It’s very important to spread the facts,” she said, “because a lot of the things that motivate people are feelings and emotions. But those aren’t the facts.”

The other half, which includes her father, just isn’t convinced there’s no threat.

Aragon said her father named her sister America because he was so proud of his new country, but to some degree that pride has turned to suspicion.

Nevertheless, the family recognizes the opportunities afforded them in the United States. That’s one reason Aragon wants to keep working to help give others what her parents gave her.

“My parents are immigrants; I’m a U.S. citizen. … I’m going to make the most out of it because I saw how much they struggled to be where they are,” she said. “I am in a place where it’s all thanks to them. …

“And so I just want to show people that they can overcome any adversity.”