Sage Moctezuma, 22, poses for a photo in front of a window in her room at one•n•ten’s POND program housing facility in Phoenix on March 28, 2017. (Photo by Emily Balli/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX — Being 15 years old isn’t easy for a lot of people. You’re a freshman in high school and really starting to come into your own. You’re trying to figure out where you belong and what you want to do with your future.

Imagine going through your early teenage years without the support and acceptance of your family, with no place to call home, turning to drugs and living in constant fear.

That was Sage Moctezuma’s life when she was 15.

Moctezuma, now 22, was assigned male at birth but said she didn’t identify with her assigned gender. She lived as a gay male for a while, but today she is living as a transgender woman. She said her family accepted her being a gay male but struggled to accept her for being transgender, having no knowledge or tolerance for the transgender lifestyle.

“They had nothing to give me there, so I had to take off,” Moctezuma said. “They weren’t supportive or anything like that. I had to kind of make my own way for awhile.”

She began using drugs and attempted suicide twice. She left home and, for several years, lived with anyone willing to give her a place to stay.

Moctezuma is one of thousands of young adults in the United States who have dealt with homelessness due to gender identity or sexual orientation.

Stories from one•n•ten

In a 2015 study, the Williams Institute, a think tank at the University of California, Los Angeles that conducts research on sexual orientation, gender identity law and public policy, found that of youth accessing homelessness services, an average of 20 percent identified as gay or lesbian, 7 percent identified as bisexual and 2 percent said they were questioning their sexual orientation.

In terms of gender identity, 2 percent of people in the study identify as transgender female, 1 percent identify as transgender male and 1 percent identify as gender-queer, someone who does not subscribe to conventional gender distinctions and identifies with neither, both or a combination of male and female gender roles.

Those percentages are significantly higher than estimates of the LGBT share of the general population.

According to a 2016 Gallup poll, 4.1 percent of the American adult population identify as LGBT. The True Colors Fund, an organization that works to end LGBT youth homelessness, estimates that LGBT youth represent 7 percent of the total youth population. (Gallup and the True Colors Fund did not report data from those who identify as questioning.)

“We see across the country anywhere between 20 and 40 percent of young people who are homeless identify as LGBTQ,” said Kristin Ferguson-Colvin, an associate professor at Arizona State University’s School of Social Work, who has 23 years of experience working with and researching homeless youth. “The LGBTQ young person population has higher risk levels around family abuse, family rejection, family violence – all of which are precursors for these young people leaving home.

“They either run away because their families reject them with their coming out experience, or their families kick them out. These young people oftentimes have much higher risk of not having a support system or family to fall back on than heterosexual or cisgender young people.”

Once these LGBTQ young people become homeless, they may be able to find a shelter where they can stay, but many shelters are ill-equipped to meet their specific needs.

Moctezuma experienced this during her time at a residential education and job training program for at-risk youth in Phoenix.

“My first day there there was just fighting,” Moctezuma said “I didn’t have anywhere else to go, and this was Phoenix for me. A lot of the staff were trying to pressure me into being a certain way even though I was pushing my way to the female side. I did get into the female side, but I don’t think they had a lot of resources to give me, and I was looking for a lot of them. There just wasn’t any resources for me, I just kept finding myself in trouble, doing more drugs and more drinking. It was a terrible experience.”

In Arizona, one•n•ten, a local nonprofit organization, is the only organization with an LGBTQ-specific homeless youth shelter, although some shelters have received training on being LGBTQ inclusive.

Melissa Brockie, director of prevention and wellness at Tumbleweed Center for Youth and Development, said her staff has been trained on how to be inclusive.

“We serve LGBTQ clients, especially in our resource center youth can come to groups, and we make it an inclusive and safe space,” Brockie said. “We’ve been trained by one•n•ten to ensure that we’re providing culturally and gender specific sensitive services.”

However, Brockie said oftentimes Tumbleweed will refer LGBTQ youth to one•n•ten because they have more resources available.

Data collection on this population is sparse

Every year, the Maricopa Association of Governments coordinates the Point-In-Time Homeless Count, where hundreds of volunteers take to the streets to identify how many people are homeless in Maricopa County. This measure is required by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Volunteers approach people on the street and ask them a series of questions.

In recent years, the MAG revised questions about gender identity and sexual orientation in order to get a better, more inclusive picture of how many LGBTQ individuals are experiencing homelessness. However, the questions about gender identity and sexual orientation have varied over the years, making the issue of LGBTQ youth homelessness difficult to track over time.

In 2013 and 2014, for example, the survey included a question about gender identity and a question about sexual orientation. In 2015, 2016 and 2017, the survey still included a question about gender identity, but it did not include a question about sexual orientation.

Related links:

Hundreds of volunteers help document homeless during annual street count

Advocates say ending Arizona’s veteran homelessness is in reach

According to Kinari Patel, human services planner at MAG, HUD provides a template for the survey. MAG is required to follow the questions on the template but may add or tweak questions. This year, the HUD template didn’t ask about sexual orientation, and MAG did not add a question to do so.

Although the data collected from the PIT count is very useful for tracking the overall homeless population, the inconsistency of the questions makes it unclear if LGBTQ youth are experiencing more or less homelessness over time. In addition, there is no clear data on exactly how many homeless LGBTQ youth there are in Arizona.

One of the authors of the 2015 Williams Institute study, Soon Kyu Choi, a policy analyst at the institute, said that collecting data on this population of young people can be challenging but is necessary in order to address the issue.

“There has been a lot of discussion around data collection, and I think that’s an important step for a lot of people working on this issue so that they can ask for more funding or more attention,” Choi said.

Some resources are available, but not enough

one•n•ten has a variety of resources and services for LGBTQ youth, including housing for those experiencing homelessness through the Promise of a New Day program. POND offers each person a single unit apartment, basic living supplies and other resources to help residents get back on their feet. The POND program started with five young people in October 2012, and today it houses and serves 33 youth at the shelter.

According to Stacey Jay Cavaliere, programs director at one•n•ten, the nonprofit gains funding from a variety of sources including the City of Phoenix, The Bob and Renee Parsons Foundation, corporate support and individual donations from community members.

However, Cavaliere said gaining funding for all of these services isn’t easy.

“We are consistently looking for new or renewed funding opportunities to support this program,” he said. “With an unprecedented number of youth experiencing homelessness in Maricopa County, we are extremely dedicated to serving and supporting more youth as we are able.”

Advocates say a more accurate count of how many homeless LGBTQ young people there are is the first step to gaining both attention and funding.

“There has recently been some homeless funding cuts from our federal government,” Sarah Kent, POND housing and program director, said. “Nonprofits having the money to do these sorts of things sadly is getting a little bit more challenging. I think getting true numbers would help because a lot of funding sources require that statistical data.”

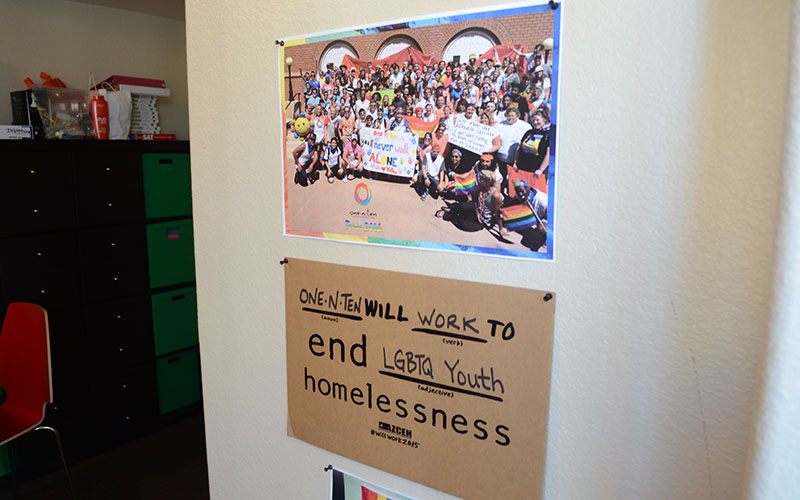

A sign on the wall of an office at One n Ten’s POND program building in Phoenix, Arizona on March 3, 2017. (Photo by Emily Balli/ Cronkite News)

Cavaliere agreed and said he thinks there’s still a lot of work to be done in the community for this population.

“We need a better ‘snapshot’ of what youth homelessness looks like in our community to accurately relay the message,” he said. “This, however, needs to be a community-wide effort. There are still way too many youth on the streets or in unstable living environments. Funding is scarce, resources are often difficult to access. So I would say we have a lot of work to still do.”

Cavaliere said he believes the solutions are collaboration, more attention and increased opportunities to support programs like POND.

In December 2015, after hearing about one•n•ten’s POND program through friends, Moctezuma moved into the shelter and finally lived somewhere she felt safe and accepted.

“Being here I’ve been able to present myself as who I am, full time, without having to worry about anyone else taking that away from me,” Moctezuma said. “I was able to actually start my medical transition and actually get a job. I’m not dealing with any more stress involving people that don’t like me when I step out of my door.”