SAN ANTONIO – Cancer is now the leading cause of death for Latinos, accounting for 20% of all deaths, and according to a news release from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Latinos could face a 142% increase in cancer cases in coming years.

Those were among the concerning statistics discussed by researchers and health care providers at a conference focused on Latino cancer care, hosted by the Mays Cancer Center and the Institute for Health Promotion Research earlier this year at the University of Texas Health San Antonio.

Despite progress in cancer prevention, diagnosis and treatment, cancer disparities persist. Compared to white patients, Latinos have more incidents of stomach, liver and cervical cancer and are twice as likely to die from liver and stomach cancer, according to 2019 figures from the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health.

The American Cancer Society identifies cancer is the “leading cause of death among Hispanic people,” accounting for 20% of deaths. Cancer experts at the San Antonio conference said lack of early screening in the Hispanic population plays a large role in higher rates of cancers like cervical cancer.

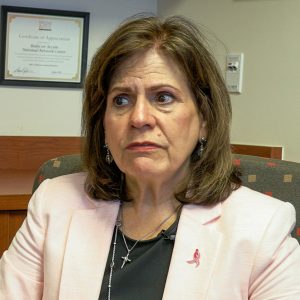

Amelie G. Ramirez, associate director of cancer outreach and engagement at Mays Cancer Center, discusses the leading cause of death for the Hispanic community, on March 27 in San Antonio. (Photo by Maria Garcia/Cronkite News)

“Cervical cancer is something no one should die of anymore,” said Amelie G. Ramirez, associate director of cancer outreach and engagement at UT Health Mays Cancer Center. “Yet, we have higher rates of unscreened and people losing their lives to cervical cancer because they’re not coming in early enough.”

Early screenings can detect cancer in the cervix, breast, colon and lung before they cause noticeable symptoms and, in some cases, improve the chances of successful treatment. Delays in cancer care could decrease survival rates, increase costs of care and prompt additional health problems. For cervical cancer, women are encouraged to begin regular Pap smears at 21 years old, regardless of their sexual activity.

Recommended screening ages for breast and colon cancer have been lowered as health providers see an increase of those cancers in younger patients. The U.S.Preventive Services Task Force now recommends breast cancer screening start at age 40, and colon cancer screening start at 45.

Dr. Emmalind Aponte, oncologist and hematologist for Texas Oncology, a statewide private oncology practice, noted the Hispanic community lacks access to care and education on cancer screenings and its benefits.

While Aponte believes that expanding access could bring more patients in for early screenings, she found that other problems could stand in their way, like language barriers, cultural traditions and lack of transportation.

“Being able, for patients, to actually have health insurance,” Aponte said. “Many Hispanics do not have health insurance, and another one would be something as simple as transportation; patients don’t have a way to get where they can do the screening.”

In 2013, Maricarmen D. Planas-Silva was diagnosed with thyroid cancer after doctors found a 9 centimeter malignant tumor. Prior to her diagnosis, Planas-Silva hadn’t regularly gone to a doctor because her time and energy were focused on being a caregiver. Treatment involved the removal of her thyroid and hormone medication to replace the hormones she can no longer produce naturally.

Oncologist and hematologist for Texas Oncology, Dr. Emmalind Aponte, returns to work on March 28 at Gonzaba Medical Group’s Woodlawn Medical Center, where she provides care to numerous Hispanic patients in San Antonio. (Photo by Maria Garcia/Cronkite News)

After surviving cancer and watching a close friend from her native Peru die from breast cancer, she realized Hispanics need help getting through cancer. Planas-Silva provided that help by founding Angelmira’s Center for Women with Advanced Cancer, a volunteer group of female patient advocates dedicated to helping other women with metastatic cancer.

“We try to be an extra hand and extra heart for those who are struggling with cancer,” Planas-Silva said. “We have a lot of Latinos that are, you know, going through cancer, and they don’t have insurance, and they don’t have resources. So we have been helping them.”

Advocates at Angelmira’s Center work with stage 4 patients and their families, helping them navigate paperwork, insurance, transportation, language barriers, groceries and more. Even though Houston is Planas-Silva’s home base, she and other advocates throughout South Texas offer their advice, comfort and training to patients at the Mays Cancer Center in San Antonio.

For the first time, the San Antonio conference, Advancing the Science of Cancer in Latinos, included a group of Latina advocates discussing their cancer experiences and advocating training. Over 280 individuals attended the conference. Advocates and researchers stressed the importance of diverse representation in clinical research, trials and daily provider care.

“Having the information from diverse communities helps us better understand the type of cancers that Latinos are being impacted by the most and then sort of what interventions we can do,” said Erica Martinez Zumba, director of community and participant engagement at the All of Us Research Program at the National Institute of Health.

Hispanic involvement in research could help improve cancer care access and education, according to Zumba and Ramirez. Yet, those involved in cancer research and care want more action.

“We need more answers,” Ramirez said. “I used to call liver cancer, stomach cancer, gallbladder cancer, kind of orphan cancers because nobody was really doing research in them … but those are the cancers that are affecting our community.”