PHOENIX – Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable death and disease in Arizona and across the U.S. Federal and state officials are now targeting flavored tobacco products, particularly menthol, for having made the problem worse.

The American Lung Association recently joined Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes and attorneys general from other states urging the Biden administration to ban menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars.

JoAnna Strother, senior director of advocacy for the American Lung Association in Arizona, said the association has been fighting to get menthol cigarettes out of stores since 2011.

“What it would do is end the sale of menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars in the U.S. and that will really help to save lives. We know when these products are taken off the market, then no one is using them,” Strother said.

“Removing all flavored products from the market including flavored e-cigarettes is really important to protect the health of this next generation that we don’t want to see addicted to tobacco products.”

The lung association’s annual State of Tobacco Control report gave Arizona three failing grades out of five categories. Arizona failed on its policies relating to tobacco prevention and cessation funding, tobacco taxes and flavored tobacco products.

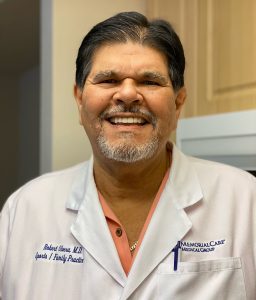

Dr. Robert Olvera, former medical director of Bristol Park Medical Group’s family clinic in Santa Ana, California, saw African American patients with health problems from smoking. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Robert Olvera)

According to Dr. David Tom Cooke, a thoracic surgeon at University of California, Davis and a medical spokesperson for the American Lung Association, menthol tobacco products have been disproportionately marketed to Black communities and communities of color in the U.S. Ten years ago, The Center for Black Health & Equity launched No Menthol Sunday, a national day of observance every May with the goal of “engaging the community in a discussion about the number one killer of Black Americans, tobacco.” This year No Menthol Sunday will be May 19.

A 2021 study of African American adults in Minnesota found that 59% either thought menthol cigarettes to be less harmful than non-menthol cigarettes or were unsure of the harm menthol cigarettes could cause.

Dr. Robert Olvera, former medical director of Bristol Park Medical Group’s family clinic in Santa Ana, California, spent his career treating African American and other minority patients and said he saw the adverse and lasting health problems from smoking. According to Olvera, menthol cigarettes are worse than non-menthol cigarettes because the cooling effect and taste make the products seem easier to smoke. This can be dangerous because consumers may confuse easier with healthier.

“I think they were worse because they had to add more chemicals into the filter to achieve that quote-unquote smooth taste. There’s tons of tobacco that has particulate matter in it that nobody should be inhaling … and then the filter has to have so much particulate matter put into it to filter the cigarette,” Olvera said.

“The tobacco industry has executed a calculated, menthol-centered strategy to establish a strong presence in African American communities, appropriate African American culture, and create a dependency on tobacco funding,” according to The Center for Black Health and Equity’s website.

Claudia Rodas, director of the southern region for the advocacy organization Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, said the reason the tobacco industry heavily targets Black and brown communities and fights against a menthol ban is because it makes billions of dollars a year selling menthol cigarettes alone.

“That’s a huge market share for them. While they’re fighting for their profits, we are fighting for people’s lives,” Rodas said.

Olvera said the reason big cigarette companies continue to push menthol cigarettes in American communities is to keep sales high.

“Menthol is particularly attractive to minority communities for various reasons,” Olvera said. “Particularly because menthol is soothing. I don’t know per se if the cigarettes are stronger, but the taste is better.”

Olvera said menthol cigarettes were marketed as more relaxing, more enjoyable, easier on the throat and had a crowd appeal.

“I remember seeing advertisements with doctors smoking and drinking a cup of coffee,” said Olvera, who lived and worked in a primarily minority community.

A smoker in downtown Phoenix on March 28. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

The marketing has had lasting effects on African Americans and other minority community members. A 2021 report from the Food and Drug Administration estimated that nearly 85% of all Black smokers smoke menthol cigarettes, compared to 30% of white smokers.

Olvera said he has seen a higher incidence in Black smokers of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, lung cancer and heart problems, as well as circulation problems in the legs.

This targeted marketing started in the 1960s. One document from the tobacco industry outlines plans to give menthol cigarettes to the social leaders in black communities along with those who have daily contact with lots of people, including taxi drivers, barbers and hotel workers.

Other tobacco industry documents outline that after a ban on advertising in the media went into effect, the industry switched to billboards and ads inside public transit commonly used by the Black community.

All of these documents and more can be found on the University of California, San Francisco’s industry documents website on the “Tobacco” tab.

The marketing reached a pinnacle in the late 1980s when the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.planned to market a new menthol cigarette, Uptown, as an exclusively black brand. The company pulled the plug on its test-marketing plan for the cigarette after pushback from then-Health and Human Services Secretary Louis Sullivan, who is Black, and a coalition of activist organizations.

Sullivan was quoted as telling the tobacco company, the “trade-off between profits and good health must stop.”