The annual Strategic School Staffing Summit, run by Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College earlier this month, highlighted a collection of potential solutions to teacher staffing issues across the state. In this 2022 file photo, students work with a teacher at Encanto Elementary School in Phoenix. (File photo by Sophie Oppfelt/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Public school educators say they are some of the most underpaid and overworked laborers in the country.

In 2023, Educators for Excellence polled thousands of teachers about their experiences and workloads and found that while 80% of teachers are likely to spend their entire careers in the classroom, only 14 % of teachers would recommend the job to others. These striking statistics come as no surprise for educators who have been dealing with the pitfalls of school staffing shortages for years now with little to no reprieve.

The Arizona State University Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College’s annual Strategic School Staffing Summit earlier this month highlighted a collection of potential solutions, but now the question remains if any of them will incentivize teachers enough to commit to the classroom long term.

Across the school districts in the state, more and more educators are quitting or are considering leaving the profession. Against the backdrop of lack of affordable housing, the rising cost of living, political discourse and stagnant wages, the Arizona School Personnel Administrators Association (ASPAA) found that by January 2023, of the more than 7,500 teaching positions that had been vacant at the beginning of the school year, over 82% remained either still vacant or were filled by people who didn’t meet required teaching qualifications.

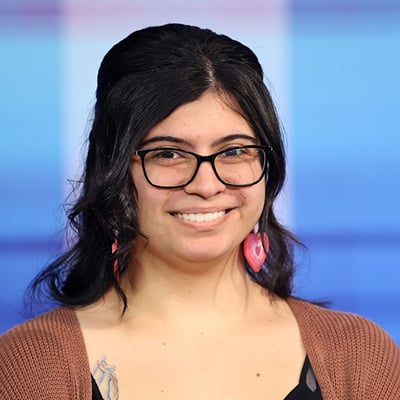

“This is a predominantly 80% female-dominated profession and so it’s expected that women do this unpaid labor for their children, for the students, because we’re seen as more maternal,” Arizona Education Association President Marisol Garcia said. “But … on the other end, Arizona educators and most educators across the country do not have family leave, do not have health care coverage for their children, do not have high rates or really great medical insurance for if we do get injured or if we do have children.”

“How are we taking advantage of this labor, this exploitation of labor particularly in a female-dominated workforce, and yet not putting up any supports that allow them to continue to be happy and healthy and stay and continue to do the job that we’re expecting them to do?” Garcia asked.

In Arizona – where the average teacher’s salary ranks 32nd in the nation, according to the National Education Association – the teachers posing this question are typically the ones considering leaving the profession.

The Next Education Workforce initiative at the Fulton Teachers College aims to tackle some of the issues plaguing classrooms by inviting presenters, educators, researchers and other experts in education from across the country to the virtual two-day staffing summit.

Honing in on staffing structure, the summit highlighted some of the main characteristics of strategic school staffing as distributed leadership, compensation structures, innovative teaming, extended teacher reach and technology that optimizes educator roles. A common theme was counting on “enabling conditions,” such as equitable and sustainable funding for schools, flexible state and district policies, strong focused leadership and access to high-quality technical assistance, in order to maintain the strategic school staffing structure.

“All of this is the set of enabling conditions, the data systems and structures. All of this has huge bearing on our ability to do this work,” Executive Director of Next Education Workforce Brent Maddin said during opening remarks at the summit. Logos of many of the organizations, higher education institutes, school districts and nonprofits that contributed and presented at the event were on full display to give, “a sense of the breadth of people that are doing this work, arm-and-arm, between universities and school systems. We are all part of the solution,” Maddin said.

Statewide policy solutions for school staffing

A proposed policy solution from Gov. Katie Hobbs seeks to have voters extend Proposition 123 and raise the State Land Trust Permanent Fund distribution, which would fund Arizona public schools over the course of 10 years. Hobbs estimates her plan would raise $118 million for school support staff, $347 million for teacher pay raises and $257 million for general school funding.

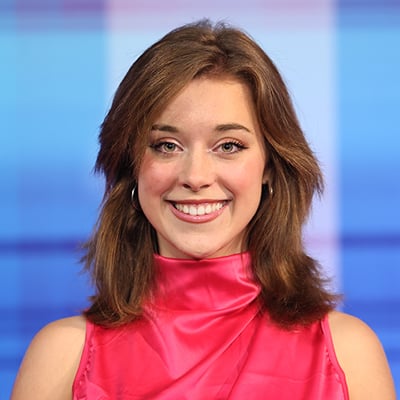

“Prop 123 might be able to mitigate a little bit of the turnover and the exodus that we’re seeing. But, by itself, it isn’t going to solve it,” Sen. Christine Marsh, D-Phoenix, a supporter of Hobbs’ plan and former Arizona Educational Foundation teacher of the year, said. “We have tens of thousands – somewhere around 60- to 70,000 certified teachers in Arizona – who won’t teach. So it really is not a teacher shortage, it is a shortage of people who are qualified and willing to teach, so there’s a lot more we absolutely need to do. With the legislative makeup the way it is, I don’t know if we’ve got very much hope of too much happening.”

The Republican plan to raise teacher pay also seeks to tap into Prop 123 but specifies funding for teacher raises and seeks to keep the land trust distribution at 6.9%, compared to 8.9% under Hobbs’ plan. In addition, Arizona Rep. Matt Gress, R-Phoenix, is sponsoring HB 2608, which passed in the House earlier this month. The bill would require the State Board of Education to conduct a retention study among school districts and charter schools.

But with varying opinions and proposals across the board, bipartisan agreement on how to fund Arizona educators seems unlikely.

AEA President Garcia said she supports Hobbs’ plan and letting districts manage how they spend their funding versus the Republican plan, which she says incentives pay per performance. “I’m excited that people are talking about this because clearly we’ve been raising the issue for forever.”