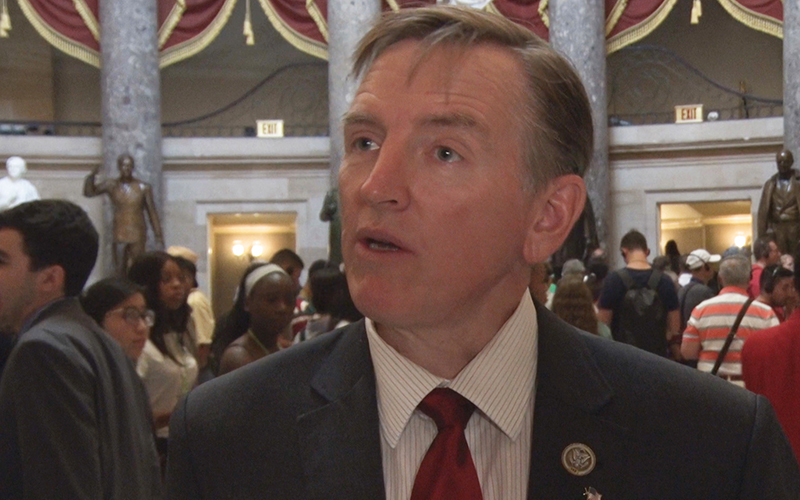

WASHINGTON – Just three months after the House censured Rep. Paul Gosar for posting a video that depicted him as a cartoon character killing Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the two found themselves on the same side of an issue.

Gosar, R-Prescott, and Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., were among 43 House members – many from the far-right or far-left ends of the political spectrum – who signed a letter Tuesday urging President Joe Biden to get congressional approval before committing any U.S. troops to fighting in Ukraine.

The 25 Democrats and 18 Republicans on the bipartisan letter are heavily represented by members of The Squad, a contingent of six liberals, as well as members of the conservative House Freedom Caucus, which is led by Rep. Andy Biggs, R-Gilbert.

Analysts said that while politics typically divides Washington, such displays of bipartisanship are not unheard of – particularly where Congress’ role in making decisions on war is involved.

Rep. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn., and Rep. Thomas Massie, R-Ky., “hardly agree on anything but … the question of American forces involving themselves in foreign conflicts,” said Jacob Rubashkin, a reporter and analyst with Inside Elections.

Besides Biggs and Gosar, Arizona Reps. David Schweikert, R-Fountain Hills, and Raúl Grijalva, D-Tucson, also signed the letter.

“Any boiling point about armed conflict and our men and women in uniform being sent into a theater of war … should require the consent and the vote of Congress, period,” Grijalva said.

Biden has repeatedly said that no U.S. troops will be committed to fight a Russian invasion of Ukraine, but he has said the U.S. will defend its NATO allies and has deployed thousands of soldiers to Europe.

Despite those assurances, Reps. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., and Warren Davidson, R-Ohio, organized the letter asking Biden to respect Congress’ power by requesting authorization before sending troops to Ukraine, citing Constitutional provisions.

Under Article 1, Congress has the power to declare war, while Article 2 establishes the president as the commander-in-chief of the military. The letter said that language was “intentionally written” so the legislative and executive branches must cooperate when making these decisions.

On Tuesday, Biden sent troops currently stationed throughout Europe to NATO member states Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia as a “totally defensive” precaution against Russian forces in neighboring Belarus.

“We have no intention of fighting Russia,” Biden said Tuesday. “We want to send an unmistakable message, though, that the United States, together with our allies, will defend every inch of NATO territory and abide by the commitments we made to NATO.”

The administration is not required to seek congressional authorization for the moves it has made so far, as there are no active hostilities present. Should Russia pose an imminent threat to the region, however, the lawmakers’ letter said the administration has a responsibility to petition Congress before leaving any remaining military personnel in harm’s way.

Rubashkin said the diverse political opinions of those on the letter appears unusual, but it is more common than most expect.

“The fascinating thing about foreign policy is how it can rearrange the sort of coalitions that we have come to see and expect in D.C.,” he said. “In this particular case … you see anti-interventionalist members of both parties sign onto an effort.”

Norman Ornstein, a senior fellow emeritus at the American Enterprise Institute, said that while Democrats and Republicans united on this front, they each came with other motives.

“In the past … there was this larger sense of protectiveness about their own institutions,” he said. “That’s not as significant anymore, especially among Republicans. They don’t care about the institutional role, they just care about their own power and, you know, finding ways to hit back at the other side.”

Rubashkin said the letter discusses “an issue that at the moment is not even on the table,” since Biden has said he intends to avoid conflict with Russia. Ornstein suggested that the letter is an attempt by Congress to assert its power in the matter of using military force.

“It’s in many ways a kind of shot across the bow to the president, especially since there’s no indication that we would engage in any kind of combat,” Ornstein said. “It’s much more a reminder: ‘Whatever happens, if you do think about this, keep in mind we’re not just doormats here.’”

Presidents in the Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq eras did not always include Congress in the decision to deploy troops, an executive incursion on congressional powers that Grijalva said must stop. Lawmakers must have their votes heard before the U.S. engages in military conflicts, he said.

“I would hope that the Biden administration understands that this is not about limiting their executive power to go to war,” Grijalva said. “It’s about instituting Congress’s role in that decision, and right now, Congress has no role and that’s got to end.”