PHOENIX – Dolores Adams, 86, recently forked over a $36 copay for prescription blood thinner, but she’s never had to before and doesn’t understand the sudden cost. She’s not alone in her confusion.

Research shows that about 80 million adults in the U.S. have limited health literacy, defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”

One survey, the National Assessment of Adult Literacy, found that the problem more profoundly affects those 65 or older, with a higher percentage considered having “below basic” or “basic” health literacy.

Health literacy became popularized in the 1990s when the first assessment revealed that many Americans are unprepared to make health care decisions. In the era of COVID-19, experts say, health literacy has grown even more important.

Harvard University professor Rima Rudd, a pioneer in health literacy, education and policy, was one of the first researchers to study the link between patients’ literacy skills and health outcomes.

In an interview, Rudd said health literacy has been studied very narrowly as an attribute of the patient alone. But she and other experts believe literacy develops – or diminishes – based on the quality of interactions between patients and health care professionals and systems.

She emphasized that it’s the provider’s responsibility to help bolster literacy, not just through availability of information but also accessibility.

“We need to approach people with dignity, not talk down to them, work with them to make sure that there is clarity and good access to information,” she said. “It’s our responsibility to make sure that information is accessible. We’ve paid too much attention to availability, and not enough attention to accessibility.”

With COVID-19, readily available information hasn’t always clearly explained what the disease is, what a pandemic declaration means, how the virus that causes COVID-19 spreads, or whether masks are an effective deterrent.

COVID-19 messaging is an example of what not to do, said Rachel Roberts, manager of community health engagement and strategy at the Institute for Healthcare Advancement, a nonprofit in Orange County, California, aimed at improving health literacy.

Older adults, in particular, “were very confused,” Roberts said.

“They didn’t have access, in some cases, to the internet or they didn’t use the internet or they just were on the TV watching news,” Roberts said. “That’s where we really saw this big gap in terms of understanding.”

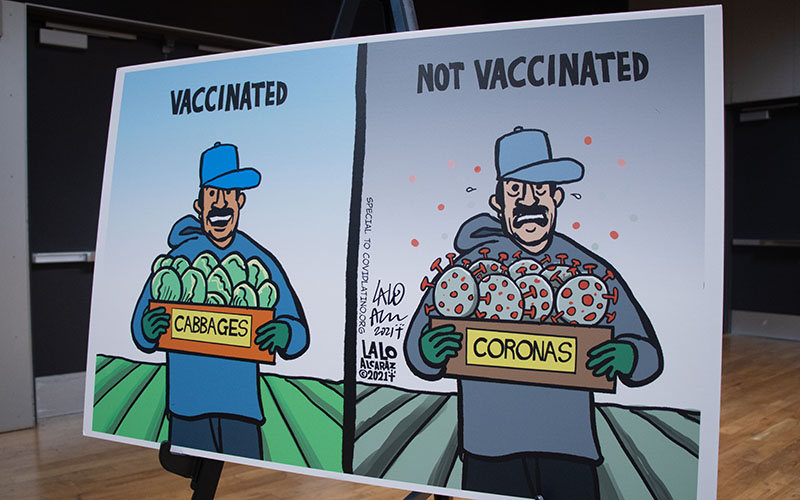

Dr. Cliff Coleman, associate professor of family medicine at Oregon Health and Science University and an advocate for efforts to improve literacy, said poor health literacy skills are a primary cause for hesitancy about COVID-19 vaccines.

A March study published in the Journal of Public Health found that people with a low health literacy score were more likely to be COVID-19 vaccine “hesitant” instead of “pro-vaccination.”

“The COVID-19 pandemic has caused all of us to really need to kind of ramp up our vocabulary,” Coleman said. “For the first time, the public is thinking about things like ‘herd immunity’ and ‘full vaccination’ or ‘full immunity’ – terms that we might use in public health environments that people haven’t been used to.”

For older adults, navigating complex health care information is even more challenging, Coleman said, especially for those suffering from cognitive decline or sensory problems, such as vision or hearing loss, that hamper communication.

“We don’t really know why older adults score lower on health literacy tests,” he said. “Specifically, we don’t know if we, as adults, sort of lose health literacy skills as we get older or if formal education has changed so much in the intervening years that people just don’t have the same foundational knowledge.

“If I’m 70 years old and I think back to what I learned about human biology way back when I was in school, all of that science has completely changed now. And it may be that my understanding is just obsolete. We just don’t really know.”

Adams, the woman who was surprised by her medication copay, acknowledged that the older she gets, the less she comprehends. After her husband was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis years ago, she became more intentional about asking doctors questions and bringing along a younger family member to appointments.

“I ask a lot of questions because if you don’t participate, they don’t offer up that information, not unless you really ask,” said Adams, who lives in Toms River, New Jersey.

Adams said she also finds frequently used medical jargon confusing.

That use of technical jargon helped prompt passage in Congress of the Plain Writing Act of 2010, which requires federal agencies to use clear communication in any publicly released information or documents. It defines plain language as “writing that is clear, concise, well-organized, and follows other best practices appropriate to the subject or field and intended audience.”

Barbra Kingsley, chair of the Center for Plain Language, a Virginia nonprofit that assists government agencies and businesses with clear communication, said the act increased support for health literacy backed by plain language.

“Plain language benefits everyone … no matter what education level, what level of expertise,” she said.

Although the use of plain language has increased across health care, the inclusion of health literacy in medical school curriculum remains limited. According to a 2010 survey of 61 medical institutions, 72% of respondents said health literacy was part of the curriculum, but the median time spent teaching about it was only three hours out of four years of instruction.

“None of these (medical school) residents have had any significant training in health literacy,” Coleman said, “at least not to the degree that it’s really stuck with them or changed their behaviors and the way they interact with patients.”

Because training is so limited, he said, many health care professionals don’t even know what health literacy means or how to use it when interacting with patients.

The increase of misinformation on such social media platforms as Facebook and Twitter only further highlight the need for more education – for both providers and patients, Coleman said.

And when messages are forwarded by friends and relatives, he added, “that can convey a sense of trustworthiness in the message that I think many people will put more stock and more value in rather than hearing it from a public service message system or public health information system.”

Like Rudd and other experts, Coleman said combating this has to begin with the provider, not the patient.

“Of course we as a society could do better in educating people, but that goes back to starting with early childhood education, and it’ll take us a long time,” he said.

“Training the health care workforce to provide clear communication at every point of contact with every patient is the way to do this … put things into the simplest message possible with every patient, every time. That’s going to be the solution.”