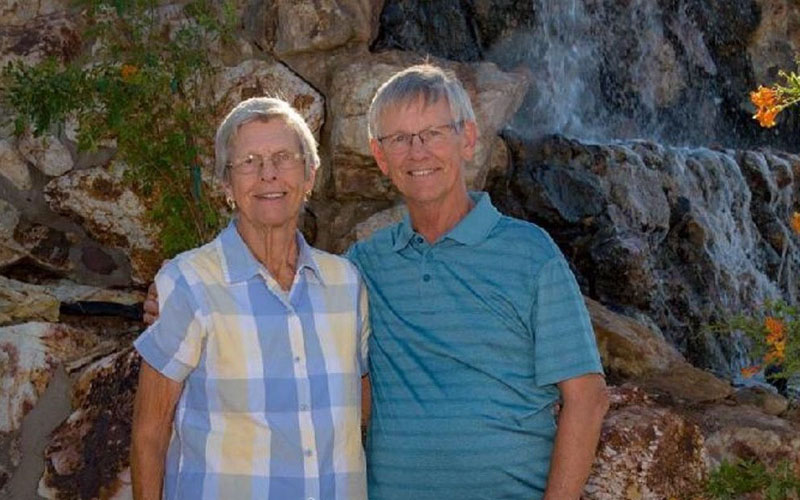

Kevin Rodrigues was 53 when he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2017. Because his cognition had already progressed to the moderate stages, he did not qualify for clinical trials for Aducanumab. (Photo by Jennifer Agema)

Kevin Rodrigues and his family – “Kevin’s Krew” – walked to bring awareness about Alzheimer’s disease. Early diagnosis can help families plan and make lifestyle changes, says Kevin’s wife, Tina. (Photo courtesy of the Rodrigues family)

PHOENIX – A trip to pick up a few things at the grocery store down the street doesn’t normally take hours.

Tina Rodrigues of Goodyear remembered how her husband, Kevin, would often take that long at the store – and then come back with different items, or would say the store didn’t have what she’d asked for.

Rodrigues realized something wasn’t right when Kevin began to display unusual behaviors: taking out the garbage but leaving it outside the bin; losing his keys and wallet; and asking the same questions over and over.

“It wasn’t until 2016 that I said, ‘There is something severely wrong’ because he could not reengage in the workforce from 2014 to 2016,” she said. “He would get a job and lose it, and he couldn’t tell me why.”

By the time Kevin was diagnosed in 2017, he was 53 and already in the moderate stages of the progressive cognitive disease. Their family had sought medical attention in 2016, but Rodrigues said her primary care physician dismissed the idea of Alzheimer’s, saying he was “too young.” Once diagnosed a year later, Kevin’s mental status would not qualify him for many of the clinical trials for those with mild impairments.

His cognition doesn’t allow him to try some of the new medicines that have been offering hope for other patients with Alzheimer’s.

Aducanumab is the first drug approved for Alzheimer’s by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration since 2003. It has shown to reduce amyloid plaques in the brain – potentially delaying cognitive and functional decline. However, there’s no evidence that it can restore lost memory or cognitive function.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced in July that coverage determinants would first be made at the local level – which is still underway – and a preliminary decision could be posted within six months and a final decision within nine months.

According to a study last year by Dr. Winston Wong, the cost to treat Alzheimer’s disease in 2020 was estimated at $305 billion, with the cost expected to increase to more than $1 trillion as the population ages.

Costs – nearly $56,000 a year – also are a concern about Aducanumab, which is administered by infusion once every four weeks and at least 21 days apart for an unspecified treatment period. Patients in the clinical trials were treated for one year.

Since the accelerated approval by the Food and Drug Administration, concerns have been raised regarding the scientific disagreement and the advisory committee’s vote against approval. And the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General announced in August that it will review the FDA’s process.

The cause of Alzheimer’s disease is not fully understood, but scientists believe that factors involve a combination of age-related changes in the brain, genetics, environment and lifestyle factors.

Scientists say a healthy brain consists of billions of neurons, which are specialized cells that transmit information to the brain, muscles and organs of the body for healthy brain functioning. But for those with Alzheimer’s disease, the lines of communication in the brain are disrupted, affecting many of the brain processes – such as memory, thinking, judgment, problem-solving, personality and movement – later leading to the inability to care for oneself, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Some people’s bodies make too many abnormal proteins when they’re younger, and that puts them at an increased risk for Alzheimer’s later, said Dr. Alireza Atri, director of Banner Sun Health Research Institute.

The highest risk factor for this disease is age, with the majority of people 65 or older, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. However, people younger than 65 may be diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s, in early, middle or late stages. Worldwide, 50 million people are living with Alzheimer’s and other dementias.

“The problem is that the proteins (amyloid plaque) start developing 15 to 20 years before people show symptoms,” Atri said. “So that’s why the benefit (of Aducanumab) is probably small.”

However, some families say every small improvement means a lot.

Tammi Lehnertz’s father, Harold Palubeskie, was diagnosed in 2017 at 73, and because he met the criteria, he could join the clinical trials run for Aducanumab by Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

Harold Palubeskie’s family is committed to finding a cure for Alzheimer’s disease. Daughter Tammi Lehrentz, right, says her dad plans to donate his brain for Alzheimer’s studies. (Photo courtesy of the Lehnertz family)

Lehnertz said four of Harold’s siblings, along with their father, also had Alzheimer’s, so it appears to be genetically tied. Harold’s family history and his early suspicions aided in getting an early diagnosis, she said.

Since taking Aducanumab’s monthly infusions in 2018, once every month, Harold has declined slightly, with his short-term memory most affected. His motor functions and long-term memory are intact, Lehnertz said, and he enjoys normal activities with his wife.

“If we can delay the progression of Alzheimer’s even by five years,” she said, “you know that’s huge.”

Initially, Harold did experience some of the known side effects – rash and fluid leakage in the brain – but both were resolved.

The most common Alzheimer’s medications have benign side effects, said Dr. Anna Burke, director of neuropsychiatry at Barrow Neurological Institute. The FDA says Aducanumab’s ability to remove plaque from the brain can make the blood vessels weaker, resulting in a fluid brain leak or a burst blood vessel.

Typically, patients won’t experience symptoms, Burke said, and the only way to know if a blood vessel burst is by closely monitoring them with MRI scans and neurological exams. She added that in some cases patients could experience things like confusion, dizziness or a headache – but those symptoms were far less common than the asymptomatic presentation.

“We have to make sure that the benefit of the patient outweighs the potential risk,” she said.

Despite his diagnosis, Kevin Rodriques and his wife enjoyed outdoor activities, but he couldn’t be left alone. (Photo courtesy of the Rodrigues family)

Despite the possible risks of Aducanumab, Rodrigues said she wouldn’t hesitate to try this drug for her husband.

“I would, and I believe my husband would, too,” she said. “Until you’re in this life and living this day to day – losing your person – the disease just eats away at everything, and there is no hope. One hundred percent we would try it with any potential risk or side effects.”

Options are limited for the Rodrigues family and others like them. Kevin Rodrigues is at the end stage – having lost his ability to communicate his needs and ability to care for himself.

Atri said it is a “hard no” for those in the later stages who want to take the drug because there is no data available to ensure safety. The original release of the drug did not provide clear restrictions, but on July 8, Biogen said the drug should be used for those with “mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease or mild Alzheimer’s disease.”

“Medicare and insurers are going to have a lot to say about this,” Atri said, “we think (as clinicians), that the population, initially, should be similar to those in those trials. Because that’s where we have safety and efficacy data.”

People with mild cognitive impairments receive the diagnosis from a physician who considers several factors: assessment of function and daily activities, input from trusted friends on how function may have changed, assessments of mental status tests, and laboratory tests and imaging of the brain’s structure, experts say.

“If this drug can get you even two years, that’s two years later of an onset and two years more that you get to live with your family,” Lehnertz said. “And two years less at the end of your life that you suffer from Alzheimer’s complications.”

Harold Palubeskie and sister Marie Madill both are living with Alzheimer’s disease. But Harold is the only family member who has qualified for Aducanumab, a drug for those with mild cognitive impairments. (Photo courtesy of Tammi Lehnertz)

Atri is encouraged that this drug could make it possible to get earlier and better detection to improve care in the future.

For those in the moderate to severe stages, Atri said, “we are trying hard (with the research), and we don’t want to leave people behind.”

“(Alzheimer’s disease is) not something that just affects PET scans and proteins,” Atri added. “It’s people, that person and the community around them.”

While the majority of research is done for those in the earlier stages, before much of the damage is done, Burke said there are medications that are being studied in the moderate stages.

The Alzheimer’s Association provides resources for families and insights about clinical studies in one’s region.

As the Lehnertz family is benefiting from the slight glimpse of hope with this drug, they are encouraged to find a cure for Alzheimer’s one day.

“My dad said from the start, use me anyway you want to. I will do anything to try and help the future,” Lehnertz said, adding that he wants to donate his brain for any Alzheimer’s study.