Arizona has carried out most executions with lethal injection since 1992, although some death-row inmates have the choice of that or the gas chamber. The state last executed a man in 2014, when the drugs that were injected into the inmate took almost two hours to kill him. (Photo courtesy Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry)

WASHINGTON – The state’s plan to execute two death-row inmates as early as this fall were derailed Monday when the Arizona Supreme Court ordered the state to first determine the viability of its execution drugs before pressing ahead.

The order came after the state acknowledged that the pentobarbital it planned to use in the executions would only be good for 45 days, not the 90 originally claimed – and after Attorney General Mark Brnovich asked the court to cut the briefing schedule in half to account for that error.

Critics said that move showed Brnovich’s “extraordinary arrogance” in trying to speed up the executions of Frank Atwood and Clarence Dixon, who were sentenced for separate decades-old murders.

Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said Brnovich’s effort to press ahead with the executions “has nothing to do with carrying out the law” or with fairness. He said it is just “a way of trying to expedite executions at any cost.”

But a spokesperson for Brnovich said that both Atwood and Dixon have exhausted their appeals and the families of their victims deserve justice.

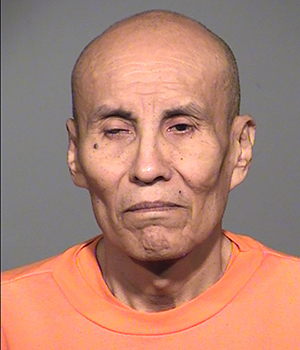

Clarence Dixon was already serving life for a sexual assault when DNA linked him to the 1978 murder of a woman in Tempe, which led to his death sentence. (Photo courtesy Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry)

Brnovich “will continue to fight for victims and their families,” said Katie Conner, the spokesperson. “Justice delayed is justice denied.”

Defense attorneys said the most recent problems with the state’s execution protocols are just the latest example of Arizona’s “troubled history” when it comes to carrying out “fair and legal” executions.

“The state’s precipitous request for a briefing schedule before it had secured accurate information about the shelf life of its compounded pentobarbital is just the latest in Arizona’s problematic handling of execution drugs,” said Dale Baich, a federal public defender who is representing Dixon.

“Arizona has had a history of acting improperly and without regard to fairness or the law when it comes to executions,” Dunham said.

The state has not carried out an execution since 2014, when the lethal injection that was supposed to kill convicted murderer Joseph Wood instead left him snorting and gasping on the execution gurney for almost two hours.

After that, the state attempted to import lethal injection drugs that were confiscated at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport by customs officials. Its troubles with lethal injection led the state to invest in the rehabilitation of its gas chamber, which was last used in 1999. That caused an uproar when critics said the state planned to use a chemical related to the gas used during the Holocaust.

The latest execution efforts began in April, when Brnovich said he would push for the executions of Atwood and Dixon. Records obtained that month by The Guardian show that the state bought $1.5 million in lethal injection drugs.

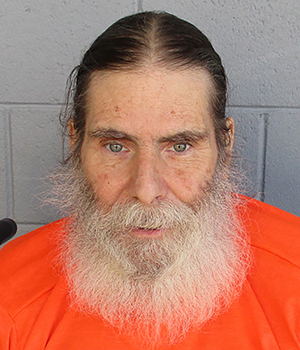

Atwood has been on death row since 1987 for the 1984 kidnapping and murder of an 8-year-old Tucson girl. Dixon was serving a life sentence for an unrelated sexual assault when a DNA match linked him to the 1978 rape and murder of an Arizona State University student in Tempe, for which he received the death penalty.

Brnovich asked the Arizona Supreme Court to set a hearing schedule for the executions, based on a statement from an Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry pharmacist, who said the state would have 90 days to use the pentobarbital once it was compounded for lethal injection.

The court granted that motion in May, clearing the way for the executions to be carried out as early as September.

But in June, Brnovich filed another motion citing a statement from the same pharmacist who said the drugs would only be good for 45 days after they were compounded, and he asked the court to cut the schedule in half. The corrections department did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

State officials are hoping to set an execution date for Frank Atwood, convicted in the 1984 kidnapping and murder of an 8-year-old Tucson girl. (Photo courtesy Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry)

The court Monday rejected Brnovich’s latest motion and reversed its May order that set a schedule. The court said the state could renew its scheduling request “after specialized testing to determine a beyond-use date for compounded doses of the drug.”

“The Arizona Supreme Court correctly recognized that the state is unprepared to carry out an execution in a safe and legal manner,” Baich said.

The shift did not come as a surprise to Atwood’s attorney, Joseph Perkovich, who said the evidence showed all along that the drugs planned for the execution have a 45-day shelf life once compounded.

Perkovich said the latest order “derails the attorney general’s reckless campaign to resume executions and affords Arizona the time to conduct the steps to establish the adequacy of its compounded pentobarbital for its intended purpose.”

Dunham called it just another instance of the state’s “incompetence” in death penalty cases.

“Here, the incompetence in not knowing the shelf life of the execution drug, is compounded with the arrogance of trying to use the prosecution’s own error as a way of further limiting the defense opportunity to respond and further limiting the courts opportunity to learn the facts,” Dunham said.

“In the rush to carry out executions, Arizona didn’t do its due diligence,” he said. “Before you spend $1.5 million dollars of taxpayers’ money, you should know whether or not you are going to be able to use the drugs.”