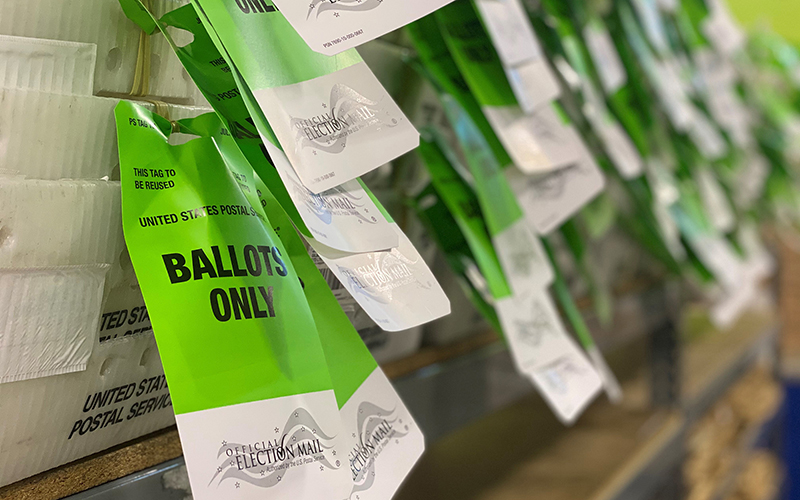

The Supreme Court upheld two Arizona election laws that critics said made it harder for minority voters to cast a ballot, in violation of the Voting Rights A Act. But the court ruled 6-3 that the rules did not target any group and were no more burdensome than any voting requirement. (File photo by Nathan O’Neal/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – The Supreme Court Thursday rejected claims that Arizona’s ballot-harvesting and out-of-precinct election rules discriminate against minority voters, a ruling that one critic said “takes a sledgehammer” to equal voting protections.

The 6-3 ruling said that while the state laws may result in some voters’ ballots being rejected, they do not “exceed the usual burdens of voting” and do not affect one group of voters more than any other.

In dissent, Justice Elena Kagan said the majority’s “tragic” opinion rewrites the Voting Rights Act “to weaken … a statute that stands as a monument to America’s greatness.”

But Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich called the decision “a win for election integrity safeguards in Arizona and across the country.”

“Fair elections are the cornerstone of our republic and they start with rational laws that protect both the right to vote and the accuracy of the results,” Brnovich tweeted after the court handed down its ruling in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee.

Critics – from President Joe Biden down to local voting rights advocates – said the ruling guts a critical piece of the Voting Rights Act that the court weakened in a separate case eight years ago. It comes as state legislatures considered record numbers of voting restriction bills this year.

“Today’s decision takes a sledgehammer to that foundation (of equal access to voting) and gives a green light to states like Arizona to enact further restrictions that target minority voters and limit their ability to exercise their right to vote,” said Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Tucson, in a prepared statement.

The ruling concerned Democratic challenges to Arizona’s 2016 ballot-collection law, which made it a felony for anyone other than a family member, caretaker or letter carrier to turn in a voter’s ballot. It also ruled on the state’s longstanding policy on ballots cast outside a voter’s precinct, which requires election officials to reject any ballot cast in the wrong precinct – thus voiding the voter’s choice in national and statewide elections not related to precincts.

Advocates said those rules targeted Black, Hispanic and Native American voters. They rely more heavily than others on mail-in voting and are more likely to face confusion about where to vote, because of shifting precincts, and have transportation issues that make it hard to get to the right precinct, the advocates said.

Two federal courts upheld the state’s policies, but the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in 2020 that the rules had a disproportionate impact on minority voters. The court said that violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits any procedure that makes it harder for anyone to vote “on account of race or color.”

The Supreme Court reversed that ruling Thursday in an opinion by Justice Samuel Alito, who wrote that whatever hurdles the policies impose fall on all voters evenly and are no more than squarely the “usual burdens of voting.”

“A policy that appears to work for 98% or more of voters to whom it applies – minority and non-minority alike – is unlikely to render a system unequally open,” Alito wrote.

He cited data from Arizona’s 2016 general election that showed that “a little over 1% of Hispanic voters, 1% of African-American voters, and 1% of Native American voters” who cast a ballot on Election Day, did so in the wrong precinct. That compared to a rate of 0.5% for non-minority voters, he said.

“The mere fact there is some disparity in impact does not necessarily mean that a system is not equally open,” Alito wrote.

But Kagan said those numbers can make a difference in an election.

“A rule that throws out, each and every election, thousands of votes cast by minority citizens is a rule that can affect election outcomes,” she wrote. “If you were a minority vote suppressor in Arizona or elsewhere, you would want that rule in your bag of tricks.”

While the rules may not be discriminatory on their face, they are in effect, she said. The out-of-precinct policy results in “Hispanic and African American voters’ ballots being thrown out at a statistically higher rate than those of whites,” she wrote, and the ballot-harvesting ban makes voting “meaningfully more difficult” for Native Americans who “need to travel long distances to use the mail.”

Kagan said Section 2 should be interpreted broadly to guarantee a fundamental right, but that the majority instead “undermines” a law it considers too “radical.” Section 2 should apply to the Arizona rules, she said, but “The majority reaches the opposite conclusion because it closes its eyes to the facts on the ground.”

Ryan Snow, an attorney with the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, called the ruling just another example of voting rights advocates and a conservative court butting heads. And it won’t be the last time, he said.

“There’s going to be more litigation,” Snow said. “In the Supreme Court’s ruling they said they will take up more voting rights concerns, so it certainly won’t be the last.”

Korina Iribe, voting rights activist with the Movement Voter Project, called the ruling an example of attacks from state legislatures on ballot access for some voters in response to the 2020 elections.

“Elected Republican officials are saying this has to stop, because they saw people get out and vote” in the last election, Iribe said.

But Lori Roman, president at the American Civil Rights Union, said “the argument against voting integrity laws are subjective and not based on facts.” She added that Arizona had merely enacted “common-sense election laws” which “should make it easier for states that are trying to protect the security of their elections going forward.”

Niles Harris, executive director at Honest Arizona, criticized Brnovich for pursuing the case that “undermined the most important voting rights law enacted in the 20th century,” a comment echoed by Grijalva.

“Once again, a conservative court has gutted a critical provision of the Voting Rights Act and made it more difficult for minority voters to prove discriminatory intent when state legislatures pass new voting laws,” Grijalva said.

Snow said the ruling will make it harder for advocates to continue their work, but that it is not over.

“It’s up to advocates to do a very thorough job of presenting the facts and proving that voting processes are not equally open,” he said.