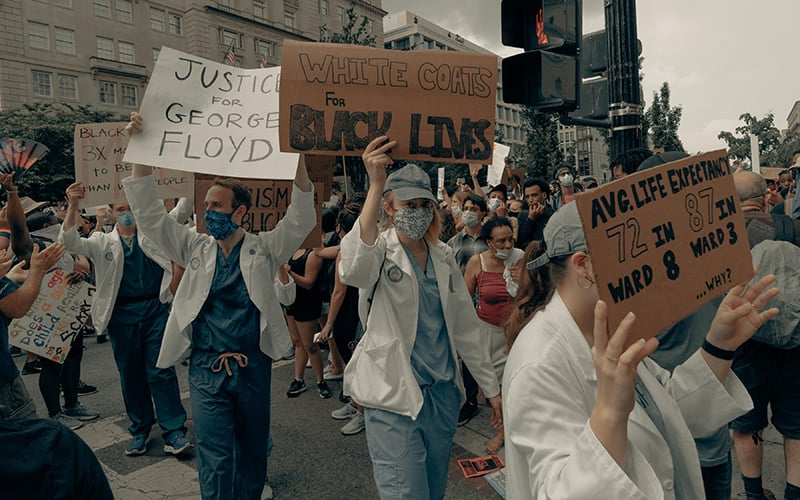

Doctors and nurses joined protesters around the country at Black Lives Matter rallies held in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd last year. The deaths of Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other Black people at the hands of police sparked a new racial reckoning, and several governors and state legislators have since declared that racism is a public health crisis. (Photo by Clay Banks/Unsplash)

PHOENIX – Amid moves by some states to declare racism a public health issue, experts are looking to medical schools to identify strategies to improve care for people of color and eliminate disparities related to a patient’s race or ethnicity.

Dr. David Acosta, chief diversity and inclusion officer with the Association of American Medical Colleges, said students’ training and exposure regarding racism in health will help effect needed change.

“It’s going to require certain attitudes, behavioral changes … constructing the knowledge base so that everybody – not just students of color – but everybody now becomes aware in medicine, nursing, pharmacy, whatever health profession,” Acosta said.

The deaths last year of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Dion Johnson and other Black people at the hands of police sparked a new racial reckoning, and governors in Michigan, Nevada, Wisconsin and other states issued executive orders declaring racism a public health crisis.

A slew of city councils and county governments passed similar resolutions, while other states established antiracism work groups or are reviewing policies and addressing institutional racism in public health, criminal justice and other areas.

In Arizona, no action has been taken by Gov. Doug Ducey or the Republican-controlled Legislature to make a formal declaration.

State Sen. Martín Quezada, D-Phoenix, introduced a resolution last year asking legislators to commit to dismantling racism and increasing education around how racism affects health, and to support policies to improve health in communities of color.

Experts are looking to medical schools to identify strategies to improve care for people of color and eliminate disparities related to a patient’s race or ethnicity. Erika Johnson, a 2020 nursing school graduate from the University of Arizona, has committed to mentoring Black students. She says: “The experience of racism is not one of just an annoyance. Those things have real biological impacts.” (Photo by Erika Johnson)

That proposal died with no action taken. Quezada reintroduced the measure last week as the new legislative session got underway.

Experts in diversity and inclusion believe one of the first steps in dismantling racism in health starts with medical institutions. However, the number of students, faculty and professors of color within medical schools remains low.

A 2019 report by the Association of American Medical Colleges found 7.1% of students enrolled in medical school identified as Black and 6.2% as Hispanic, while a scant 0.2% were American Indian or Alaska Native. Nearly half of accepted applicants in medical schools across the country were white in the 2019 school year.

The AAMC is a nonprofit, based in Washington, D.C., dedicated to transforming health through medical education, health care, medical research and community collaborations.

The group’s research shows that medical school faculty members also remain predominantly white and male, at 63.9% and 58.6% respectively.

Erika Johnson, a 2020 nursing school graduate from the University of Arizona, had always wanted to follow in her mother’s footsteps by becoming a nurse.

Johnson, who is Black, said she is confident her education gave her the tools to combat racism in health, but she knows that’s not always the case at other schools.

While finishing her bachelor’s degree in public health at UArizona, Johnson took a community health course in which students were assigned to an underserved population and tasked with immersing themselves into the community to develop proposals to improve health care.

“We met the owners of businesses and people who lived in the area within our population and talked to them about what they thought were the struggles in their community, and then we created a whole project about health disparities and how we can combat those as nurses,” she said.

Gwenetta Curry is a lecturer on race, ethnicity and health at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland who has extensively researched health disparities, their causes and possible solutions. Curry agreed that education is a key factor in addressing and one day eliminating such disparities.

“Increase education about racism, and let’s not try to rewrite history and make it look one way that it wasn’t,” she said. “Be very honest and clear about how these communities have been structured.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted differences in health outcomes and care among people of color.

Data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that while white people have the highest overall percentage of COVID-19 cases in the nation, racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately affected by the disease and are dying at higher rates.

Curry and other experts point to social determinants of health, including poverty, housing, access to health care and healthful foods, as well as institutional racism and bias in treatment and care, as just some factors worsening the pandemic among communities of color.

“We talk about racism being a public health issue because racism is the reason these communities are in the conditions that they’re in,” Curry said.

Johnson agreed: “The experience of racism is not one of just an annoyance. Those things have real biological impacts.”

She hopes some of the public declarations about racism and public health are more than toothless proclamations.

“Now that racism is a classified public health issue, hopefully more research might go into the topic to figure out how to help it so that people who are faced with health disparities won’t have to continue to deal with that kind of stress,” Johnson said.

To do her part in diversifying the medical field, Johnson, now working at Banner University Medical Center in Phoenix, has committed to mentoring Black students.

“There’s less role models out there for people of color that want to go into health care,” Johnson said. “It seems like the hardest issue with this type of thing is just knowing which track to take, so I want to be there for anybody that needs help or advice.”

Acosta, with the medical colleges association, said everyone needs to take responsibility for their role in seeing any type of change, regardless of having a medical degree or not.

“You have to take ownership,” he said. “And you have to feel very committed to this, that this is my obligation, my social obligation, my social contract to be one to do this.”

Cronkite News researchers Gianluca D’Elia, Sinead Hickey and Emily Schmidt contributed to this report.