PHOENIX – It’s been a quiet day on Zoom for Kylie Boyd and Alexandra Shilen. Occasionally, some student volunteers pop into their online room to check in or ask a brief question, then pop back out to hit the phones.

On this fall afternoon, Boyd and Shilen are overseeing 13 volunteers who are calling residents in four Arizona counties to ask questions about COVID-19.

The group is executing two functions that health experts say are essential to preventing the spread of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 and eventually ending the pandemic: contacting people who have tested positive for the disease and tracking down anyone who may have been exposed.

Boyd and Shilen are coordinators for the SAFER team at the University of Arizona. For 15 years, the Student Aid for Field Epidemiology Response program has trained students to investigate public health crises.

Team members used to track local outbreaks of foodborne illnesses and monitor flu cases. Now they’re tackling a pandemic that has killed 1.5 million people across the globe.

“In the beginning, it was like 10 cases … and then it was 100, and then it was 200. And then you really started to feel the growing pains,” said Erika Austhof, a UArizona epidemiologist who leads SAFER’s call center.

Case investigations and contact tracing are key to fighting COVID-19. Investigations involve calling individuals who have tested positive to gather information about their illness, travel history and recent close contacts. Contact tracing is when exposed individuals are alerted and given guidance about how to get tested and potential self-isolation.

SAFER does both, and it’s just one of a slew of groups nationwide helping underfunded public health agencies with what has become a colossal effort. Since January, more than 14 million people in the U.S. have been infected.

Ayeisha Rosa Hernandez works remotely as a member of the University of Arizona’s SAFER Team. SAFER runs a virtual call center where employees and volunteers contact those who have tested positive for COVID-19 and those who have been exposed. (Photo courtesy of Kylie Boyd)

Kristen Pogreba-Brown, an assistant professor of epidemiology at UArizona who leads SAFER, said volunteers who stepped up in the early days of the pandemic were vital in getting the work off the ground.

“We were just kind of running around with our hair on fire … and just having people say, ‘Tell me what you need help with,’ ‘We can help make phone calls,’ ‘I can help do this’ – that was extremely important in the very beginning,” Pogreba-Brown said.

In April, researchers at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security estimated that at least 100,000 new contact tracers would be needed in the U.S. to meet the demand caused by rising COVID-19 cases. But funding that many contact tracers would take billions of dollars.

Using funding provided through the CARES Act, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention awarded more than $600 million to 64 jurisdictions, including Arizona, to help with testing, contact tracing and containment.

According to a survey conducted by Johns Hopkins and NPR, the United States had more than 50,000 contact tracers in October, the most since the pandemic was declared in March.

A measure pending in Congress calls for the creation of a National Public Health Corps, similar to AmeriCorps, that would leverage existing national service structures to deploy volunteers to communities to help fight COVID-19 by doing contact tracing and other work.

President-elect Joe Biden supports the idea. His transition plan calls for the hiring of at least 100,000 people to perform contact tracing, among other functions.

A spokeswoman for the Arizona Department of Health Services said the agency has cross-trained about 600 people, both agency employees and employees of contractors, in case investigation and contact tracing. County public health departments employ staff for the same purposes.

Those investigators work in tandem with programs such as SAFER, with an aim to find and contact everyone who is infected or has been exposed to the coronavirus.

SAFER employs 46 people and has a team of more than 300 volunteers, all of whom are affiliated with the University of Arizona and the majority of whom are students. Faculty and staff at the university volunteer as well.

“We call ourselves a mini health department because we’re so large,” Boyd said.

The SAFER team launched its COVID-related efforts at the end of March. From April through September, volunteers put in almost 2,000 hours of unpaid time. The team has made about 9,000 case investigation calls and contacted over 1,000 people exposed to the virus.

The team performs case investigations in Pima, Pinal, Yuma and Maricopa counties, as well as contact tracing when anyone connected to UArizona is exposed to COVID-19.

Arizona’s first case of COVID-19 appeared in Tempe in late January, and by late March, case numbers were growing across the state. Today, over 300,000 cases have been reported in the four counties SAFER covers, accounting for 85% of all cases in the state.

On this day in October, the team has nearly 350 active cases to contact, far fewer than in previous months. That number often fluctuates week to week.

Calls to those who have COVID-19 go something like this: First, the patient is asked to confirm name and date of birth. Then come questions about how long the patient has been sick, whether the patient has any preexisting conditions, and any travel history. Volunteers work to help patients recall anyone they may have had contact with while infectious.

Because of federal health privacy restrictions, volunteers can’t even reveal that they’re calling about COVID-19 until the respondent first confirms his or her name and DOB – and sometimes patients refuse. The response rate typically is 70% to 80%.

Boyd said there is a level of mistrust the team must fight to overcome.

“Some (calls) lead to a refusal or just a voicemail or a no answer,” Boyd said. “Sometimes people hang up.

“In the beginning, we had more trust from people. I do think scamming has gotten worse with COVID and everything, so people are like, ‘Are you actually the health department?’”

Scammers mimicking contact tracers may ask for some form of payment, a Social Security number or immigration status. Real contact tracers never do that.

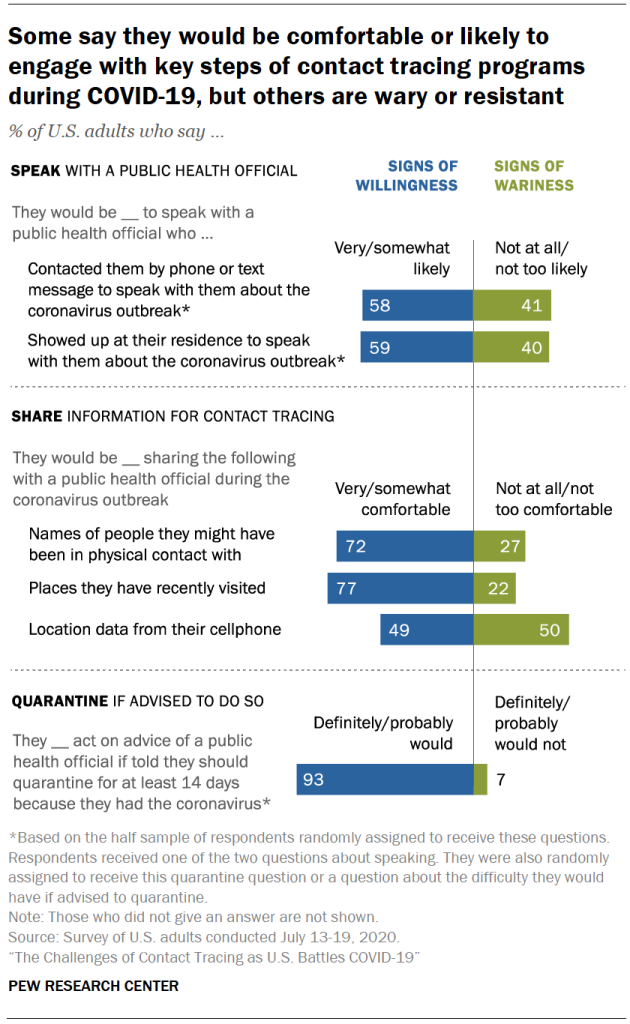

According to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in July, more than half of American adults said they would be very or somewhat likely to speak with a contact tracer who called or texted them about the coronavirus outbreak.

Having the right tone helps put people at ease, said Sana Khan, a public health research assistant at UArizona who helps with SAFER’s contact tracing.

“Making them feel comfortable sharing information with you, and not sounding overly outraged or accusatory or judgmental” is important, she said.

At SAFER, volunteers handle the case investigation calls while paid staff take the contact tracing calls, which require some level of expertise to answer questions about COVID testing and self-isolation.

Austhof said seasoned investigators typically know how to establish a relationship with the person they’re calling, rather than robotically going down a list of questions. That helps them gather more information.

Showing empathy is key, she said.

“Sometimes there’s a little bit of shame there, especially if maybe they went somewhere where they weren’t supposed to be,” she said. “Especially as college kids, if you’re underage and you’re going to a party where there’s alcohol, maybe you can get in trouble.”

Since the pandemic began, the SAFER team has spent hours on Zoom, making calls and solving problems. Austhof credits their success to the adaptability and resiliency of public health workers these past months.

“None of the systems that we have in place today existed in March,” Austhof said. “To see how far public health has come in the past six months of the pandemic has just been insane.”

Dametreea Carr McCuin, a research program administration officer with the team, recalled one Saturday when she and a team of volunteers managed to make calls for nearly 200 cases in four hours.

“You get to actually see the progress as we’re doing it,” she said, “and you get to see how much impact we made.”

Since the pandemic began, the SAFER team has been working remotely, although members recently got together for a socially distanced lunch on the grass at the UArizona campus. Some had never met their colleagues in person.

“We’re tired of COVID, too,” Pogreba-Brown said.