PHOENIX – The halls at Manzanita Elementary School are emptier than they were a year ago. But school social worker Anthony Guillen says he’s far busier, as students struggle to deal with the increased stress and psychological toll brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In a typical year at the north central Phoenix school, Guillen gets fewer than 100 referrals from teachers and parents concerned about their 600 children in grades K through 6. In just the first few months of this school year, he already has had 70.

“That’s a lot of referrals,” he said, “and a lot of them are for emotional needs.”

Many Manzanita students are Hispanic or Latino, and the school gets federal financial assistance as a Title 1 recipient, which means at least 40% of the students are from low-income families.

“They will be resilient,” Guillen said, “but right now it’s a hard time. … This is trauma.”

The pandemic has upended children’s lives and, for some, harmed their mental health. Researchers and social workers say Hispanic children may be especially vulnerable to emotional struggles, and the ramifications could be long-lasting.

The crisis has introduced a variety of stressors into the lives of children and teens: disrupted daily routines, food insecurity, isolation from peers because of school closures, increased responsibility to watch over siblings and fear of the virus itself, among other things.

Latino children may be at greater risk of psychological ramifications in large part because of what their parents are experiencing. A survey by the American Psychological Association found that people of color, particularly Hispanic adults, were more likely to report higher stress levels due to the pandemic. Nearly 2 in 5 Hispanic adults reported experiencing a great deal of stress.

Latino workers were also hit hard by the economic recession caused by the pandemic. The Pew Research Center found that job losses were most prevalent among Hispanic women, immigrants and young workers. At the same time, many Latinos are employed in jobs considered essential and have to go to work, often leaving children at home alone.

“Parents cry – they come to me and they just cry and cry – and I’m like, ‘I hear you. I’m sorry. I wish I could … make things better for you,'” Guillen said.

Even before the pandemic, Latino youth were more likely to suffer from mental health issues than other youth, including higher rates of depression and suicidal behavior, according to Salud America!, a health organization in San Antonio. These issues often are left unaddressed and untreated.

“Not only do we have a lot of kids facing adversity, families facing numerous issues, but COVID’s making that worse for everybody,” said Amanda Merck, a digital content curator at the organization.

About 56 million U.S. children are in kindergarten through 12th grade, and a recent Census Bureau report found that nearly 93% of households with school-age children reported the kids were engaged in some form of distance-learning.

For 1 in 6 children, mental health disorders begin in early childhood, making it essential that any such health needs are identified and treated early. More than 7% of kids age 3 to 17 are diagnosed with anxiety, and more than 3% are diagnosed with depression, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For kids experiencing mental health disorders, schools often are the first line of defense.

Most kids, but especially youth of color, get their mental health services from school, said Margarita Alegria, a health disparities researcher at Harvard University. With schools closed, she said, “access to a counselor or to someone that they could talk to” is harder to come by.

Alegria said research on children’s mental health following the 2008 financial crisis found that youth were very aware of their family’s economic vulnerabilities, such as a parent’s recent job loss. She said the same phenomenon is likely happening again during COVID-19.

“To assume that they’re not aware of this, under the conditions of the pandemic, would be naive,” she said.

Manzanita Elementary started the year fully virtual but moved to a hybrid model late last month. Guillen, who has been working on campus, said employees have done what they can to ensure students have access to the resources they need, whether that means food, laptops, Wi-Fi hotspots, technology support – or someone to talk to.

He and other school social workers have been teaching kids social-emotional learning online, helping them better understand their thoughts and feelings and how to get along with others.

But with staff in one place and most students in another, Guillen and other social workers said it can be challenging to provide kids the support they need.

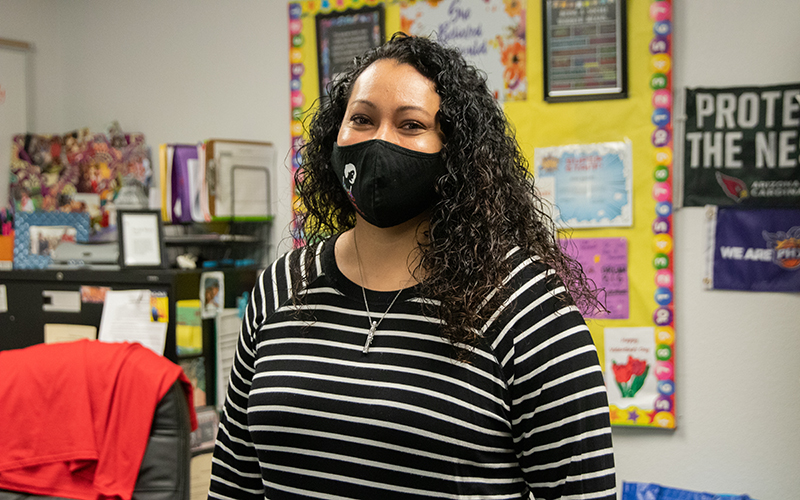

“When I’m on campus, I’m definitely more mobile, all over the place, so I have access to a lot of students and students have access to me,” said Emma Sanchez, a social worker at Washington Elementary School in north central Phoenix. When students were entirely online, she said that access decreased substantially. Since late October, Sanchez’s school has also adopted a hybrid model.

“A kid can be at home and be feeling sad, but unfortunately there’s no one around to say, ‘Oh sweetie, why are you sad?’ or ‘Why are you crying?'” she said.

Instead, Sanchez and Guillen said they try to prioritize children with the highest needs, including those referred to them by parents and teachers. They offer individual and group therapy. With younger kids, Guillen sometimes reads to them from books like “The Feelings Book,” a children’s book designed to help kids understand their emotions.

When schools went to online learning, some kids dropped off the radar entirely, Guillen and Sanchez said, because some families couldn’t adjust to the technology.

“I would say about 50% of students have logged on, 50% haven’t. So it’s been really hard,” Guillen said. “Online learning is not equitable.”

Jose Castro, 6, gets help sanitizing his hands from volunteer Pat Medwar during a recent drive to get children much-needed supplies at Washington Elementary School in Phoenix. Some social workers are reporting more referrals during COVID-19 as children struggle to cope with distance-learning and more. (Photo by Megan Marples/Cronkite News)

In south Phoenix’s Roosevelt School District, social workers who couldn’t contact families donned personal protective equipment to conduct home visits. Many of the phone numbers on file for families were incorrect or no longer worked, and emails often went unanswered, said Michelle Cabanillas, a social worker who recently left the district for the Arizona Department of Education.

“This pandemic starts to hit in different layers,” Cabanillas said. Lost jobs mean lost income, and some families weren’t able to pay for high speed internet connections.

Social workers also rely on creating a safe and private environment when talking with children. But because kids may not have access to a quiet spot at home, Cabanillas said, “It is a struggle to be able to recreate that in a virtual environment.”

Officials with Arizona State University’s School of Social Work and the Latinx Therapists Action Network created a survey to gauge the mental health of Latinos 18 and older during the pandemic. They hope to learn more about how the pandemic is affecting all family members, said Imelda Ojeda, a social worker and academic associate at ASU.

So far, respondents have said that challenges are coming from all directions. Families are facing financial strain and stress about catching the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Immigrants living in the U.S. without legal permission face the added fear of deportation and family separation.

“We are seeing the immediate effects of the pandemic and this crisis in our families,” Ojeda said. “But we feel that from the social services and mental health and child development side, this is going to have ripple effects for many years.”

Salud America!, in partnership with researchers at the West Virginia Center for Children’s Justice, oversees a program called Handle With Care, which before the pandemic connected police officers and teachers so they could better care for kids exposed to traumatic events.

During COVID-19, participating schools have had to adapt. Some created apps to track which kids have been contacted by teachers and counselors. Others make sure students get daily calls from a teacher or counselor.

Sanchez, at Washington Elementary School, said stress is so normal among students and families these days that even if a child isn’t doing well, he or she may not talk about it.

“Sometimes, kids, they don’t want to bother their teachers or they don’t want to bother their parents,” she said.

Sanchez recommends that parents take time to talk with their children about how they’re feeling, because teachers and school social workers only see the “tip of the iceberg” of what’s happening with families.

“That parent is the expert and they know their kids best,” she said. “So talk to them. Don’t be afraid to talk. Have that conversation.”