PHOENIX – The most recent album from Hataalii, a Navajo Nation indie-rock artist, closes with a pair of instrumental tracks called “Rain.”

The songs, the artist said, are inspired by the relief that rains bring in hot summer months and the idea that all struggles subside with time. The message connects to something his grandmother shared recently: a supernatural story from Navajo tradition in which mysterious tall figures from another world promise to come to humanity’s aid in a time of need.

“You should be careful, but you shouldn’t fear it – because it’ll work itself out,” he recalls her saying, as she connected the legend to the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Hataalii is the work of Hataaliinez Wheeler, 17, of Window Rock. His stage name, and first name, derive from the Navajo word meaning “to sing” or “to chant.”

Hataaliinez Wheeler, 17, poses in front of the hogan he and his dad have been building during the pandemic. The teenager says he’s inspired by “the vibe that (the hogan) will give off one day in a ceremony.” (Photo courtesy of Hataaliinez Wheeler)

Hataalii also refers to the medicine men who for centuries have used songs, herbs and sacred ceremonies to treat physical or emotional ailments of the Navajo people.

Today these traditional healers, who once played critical roles in governance and health care, are dwindling in number and influence, experts and community leaders say, even as a deadly coronavirus assaults the tribe.

This week, the Navajo Nation’s daily COVID-19 case count rose above 100 – the highest it’s been since June. In all, more than 12,000 cases have been reported within the nation, and amid this second wave, many will be looking for support from their traditional healers.

Wheeler’s music blends traditional and modern elements, using the Diné language and desert imagery over sounds derived from contemporary indie rock artists such as Mac DeMarco and classic Los Angeles psychedelic band, the Doors.

“I would say that I’m traditional,” he said. “But I’m also just like everybody else.”

That duality echoes a larger tension within the Navajo community: between the Navajo Nation’s centralized American-style government and its former, more locally focused Naachid system of governance; and between Western medicine’s pharmaceutical drugs and the hataalii’s herbs and ceremonies.

And some say the pandemic has heightened that tension.

After the CARES Act was approved in March, the Navajo Nation received more than $700 million in COVID-19 relief funding. In July, President Jonathan Nez vetoed more than $70 million in council-approved funding, including $1 million that would have supported the Diné Hataalii Association of traditional healers.

The veto drew criticism from other tribal leaders and prompted calls on social media for traditional practitioners – whom some call “the original first responders” – to receive some of the federal aid.

The original first responders should not be left out of Navajo CARES Act funding

Diné Hataałii Association releases statement in response to line-item veto by the Navajo Nation President and Vice Presidenthttps://t.co/E7G0XxDSLq

— NavajoTweets™ (@NavajoTweets) July 16, 2020

In a statement, the association called the veto “an act of disrespect and exclusion for our treasured and rare Diné Hataalii.”

“It leaves us to question why our government leaders feel as though we should not assist in relieving the pain and suffering of our people during the worst pandemic in history,” they wrote, “even though we continue to be sought for counsel and assistance.”

Nez said the funding unfairly singled out leaders of a certain spiritual belief.

“Not just the medicine man association, or the Hataalii Association, but all faith organizations should be able to get some relief,” Nez told Cronkite News. “Because even the (Christian) pastors went through some hardships.”

A counterproposal later approved provides $2 million to be divided among the Diné Hataałi Association, Diné Medicine Men Association and the Native American Church, which melds traditional practices and Christianity.

Michelle Kahn-John, a professor of nursing at the University of Arizona and secretary of the Diné Hataalii Association, said the group’s portion was $600,000.

The squabble nonetheless left some feeling slighted.

Franklin Sage, director of the Diné Policy Institute at Diné College in Tsaile, said some tribal government leaders “value the Western paradigm or the Western knowledge – Western medicine – more than their own traditional healers and practitioners and our own traditional way of life.”

“I think some people are accepting of both Christianity and tradition,” he said. “And then some people are just totally one-sided.”

Fighting COVID-19 on the front lines

Traditional healers, through ceremonies that can involve crystal, star and feather gazing, connect “with the natural world or the natural order or the natural universe that surrounds them,” said Travis Teller, a medicine man who works with the Diné Policy Institute.

Such rituals allow hataaliis to determine what’s ailing an individual – “mentally, emotionally, spiritually, physically, psychologically,” Teller said.

Then they guide people through healing ceremonies, which may involve successive nights of singing, days of physical cleansing or herbal treatments with medicinal plants. For example, sage leaves often are used for cold or sinus problems, while cedar boiled into tea works for stomachaches and other intestinal issues.

“First and foremost, hataaliis are spiritual leaders,” Teller said. “A lot of people on the reservation rely on them for guidance, leadership.”

One of the rare studies published on Native healers, a 1998 study in the Archives of Internal Medicine, found that more than 60% of Navajo patients surveyed had seen a traditional healer and about 40% used them regularly.

Teller says that when the pandemic struck, hataaliis were thrust onto the front lines. People flocked to them for help, exposing them to the virus, and several eventually died from COVID-19, he said.

The pandemic has since put a hold on in-person ceremonies, but some practitioners are using Zoom and other distance-healing options. Without the ability to go home-to-home to perform ceremonies for their patients, hataaliis are struggling financially, and Teller says they have grown frustrated.

As a professor at the University of Montana and the protégé granddaughter and niece of traditional Blackfeet Nation healers, Rosalyn LaPier straddles the divide between Western and traditional Native American medicine. She’s an ethnobotanist – an expert in the relationship between people and plants.

Historically, Indigenous practitioners who employed singing ceremonies and herbs were lumped together by Westerners and colonists and pejoratively called witch doctors.

Now, LaPier said, the ideas central to much Native American medicine – that medical problems can stem from spiritual or psychological roots and that plants can heal – are not considered outlandish.

“Increasingly academics are recognizing that there’s a connection between physical ailments and people’s mental and/or spiritual practices,” she said. “And that’s something that Indigenous people have always recognized.”

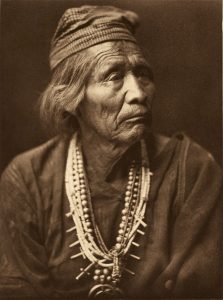

Nesjaja Hatali, a Navajo medicine man, circa 1904. Last spring, medicine men, or hataaliis, were thrust onto the front lines when COVID-19 took hold in Indian Country. They use traditional practices and herbs to heal. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Library of Congress)

She cited the work of pediatrician Nadine Burke Harris, who has written and spoken extensively on adverse childhood experiences. The central idea of that theory is at the core of traditional Native American medicine – that past traumas can linger through life and manifest physically.

As for the herbal component of traditional medicine, LaPier says mainstream medical culture has embraced that as well. Historical staples of Native American herbal medicine, such as echinacea, sage and American ginseng, have been studied for their health benefits and are widely available.

“I think that most people have some sort of herbal medicine in their household,” LaPier said.

Traditional practitioners deserve COVID-19 relief funding, she said, because they can play a key role in addressing the mental and physical fallout of the pandemic. At the same time, she cautions against misinformation about using herbal remedies to cure the disease, which has disproportionately affected Native Americans and other communities of color.

“While herbal medicines may help address some symptoms of COVID-19 and are good for our overall health,” LaPier co-wrote in a March column in High Country News magazine, “at this time they cannot prevent, treat or cure coronavirus. And believing they could do so could have dire consequences for our communities.”

Her advice on how to best boost the immune system to stave off a bad case of the virus that causes COVID-19 is familiar: get eight hours of sleep, eat healthful foods and exercise daily. Herbs work best when you’re already doing all the basic stuff, LaPier said.

Jeffrey Langland, an assistant research professor at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Center for Immunotherapy, Vaccines and Virotherapy, is studying whether herbal treatments could help fight COVID-19.

Through laboratory testing, he and his colleagues have identified about half a dozen herbs that are effective at killing the virus, he said. Once they’ve landed on the most potent combination, they hope to run clinical trials and work with a private company to bring a formulation to market.

Most of the herbs being tested come from Chinese medicine, but Langland said he would like to establish partnerships with Native American practitioners so he can scientifically test their herbal treatments and get them to more people.

“That information’s got to get to the public before it’s lost,” he said.

On the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, LaPier said there isn’t necessarily great tension between traditional and Western practices, though many people’s first inclination is to see a Western doctor – a shift she says threatens traditional ways.

“That is something that has happened over time due to colonization, due to the acculturation in our communities,” she said. “It’s something that our younger people need to solve.”

A decaying hogan sits in an expansive valley outside Piñon. Hogans are small structures that served as the traditional dwellings for Navajo people and today house traditional healing ceremonies. (Photo by Megan Marples/Cronkite News)

‘It’s definitely kind of fading’

Hataaliinez Wheeler is one young person interested in preserving traditional Navajo practices, especially those of the medicine men from whom he gets his name.

But that isn’t the case for all of his friends.

“I think it’s definitely kind of fading,” Wheeler said. “But there’s also this aspect of like, we kind of need to go back because what we’ve got now isn’t working for some people.”

Throughout his life, Wheeler has participated in a number of hataalii-led ceremonies, including a recent puberty sweat lodge ceremony. Some of them, he said, can go on all night, with hataaliis singing until the sun rises.

“After that, it’s like you just feel better,” Wheeler said, “because you’re in there with your whole family. And the hataalii will tell stories and he’ll sing songs.”

Wheeler is a senior at Navajo Preparatory School in Farmington, New Mexico, and usually stays in a dormitory during the week. But during the pandemic, he spends most of his days in his bedroom at home in Window Rock, participating in online classes and recording music.

He and his father have also been working together to build a hogan, a traditional Navajo structure used for healing ceremonies. The process has been inspirational.

Wheeler believes that spiritual convictions and mythological stories can help through hard times like this. He also sees the tension between tradition and modern, Indigenous and Western, but lives in both worlds simultaneously, with little interest in choosing one over the other.

“I wouldn’t know where I am on that spectrum,” he said. “I guess I’m just trying to make my way through all this.”