PHOENIX – Thomas Silvera and Dina Hawthorne-Silvera lost their son, Elijah, when he was just 3. He had a severe anaphylactic reaction to a grilled cheese sandwich he was given at a day care center in New York City in 2017.

Since then, the couple have run the nonprofit Elijah-Alavi Foundation to advocate for and provide resources to families living with food allergies.

They are part of a small but powerful nationwide community of Black advocates working to help those coping with severe food allergies, especially families of color.

“We are part of the pioneers who are going to really usher in the conversations and the way that people talk about food allergies and asthma,” Hawthorne-Silvera said.

Black children across the U.S. face disproportionate rates of food allergies – a fact the medical community has recognized just within the past 10 years.

One 2014 study examining allergy prevalence in children from 1988 to 2011 found increases per decade at a rate of 2.1% for Black children, 1.2% for Hispanics and 1% among non-Hispanic whites.

A 2018 study found that about 7.6% of children in the United States had some type of food allergy, and that Black children were more likely than non-Hispanic white children to have one or more food allergies.

Dr. Mahboobeh Mahdavinia, an allergy and immunology expert at Rush University in Chicago, said the medical community does not have a clear explanation for the disparities. Mahdavinia runs one of the sites for a five-year clinical study aimed at answering that question. Researchers hope to ultimately recruit about 800 children to participate.

As the medical community works to develop a deeper understanding of why these gaps exist, Black families living with food allergies say such inequities shouldn’t be surprising.

Emily Brown, with Food Equality Initiative board member Scott Akeson. Brown’s foundation helps provide allergy friendly foods through food pantries in greater Kansas City. (Photo courtesy of Food Equality Initiative)

“Black people have never had good health care in this country,” said Emily Brown of Kansas City, Missouri, whose two daughters have severe food allergies. “We wonder why we have poor health outcomes. It’s because of racism.”

Brown realized her 8-year-old, Catherine, was allergic to peanuts when she was fed peanut butter for the first time at age 1. Shortly thereafter, Catherine was diagnosed with allergies to tree nuts, peanuts, milk, eggs, wheat and soy.

“This had just a profound impact on our quality of life and our budget,” Brown said. “Our expenses quadrupled overnight. That’s hard for middle income families to absorb, but nearly impossible for low income families.”

As a Black mother struggling to find affordable and safe food for her family, Brown sought assistance from federal nutrition programs, only to discover they had little allergy friendly food available. Local food pantries had only a few options.

Brown’s experience led her to start the Food Equality Initiative, a nonprofit that aims to increase access to allergy-friendly foods and advocates for more options in federal food programs.

“Access to safe food is a health equity issue that is disproportionately impacting patients of color,” Brown said. “Being Black does not mean that you are food insecure, but being Black disproportionately impacts your ability to gain wealth and have access to the resources you need.”

One of the first studies to examine food allergies along racial and ethnic lines was published in 2011, and the findings related to disparities – and Black children, in particular – were “a surprise at the time,” said Lucy Ann Bilaver, an associate professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University.

Bilaver’s research shows that lower income families spend 2.5 times more on emergency care and hospitalization costs related to food allergies, likely because these families have less access to affordable safe food or to allergy specialists and medications.

Aleasa Word, a self-described “food allergy mom” in Atlanta, said one of the biggest challenges is encouraging people to get diagnosed and learn how to properly manage their allergies. When Word’s daughter was diagnosed with multiple food allergies, she remembers wondering how that was possible.

Word said she’s encountered some who are skeptical that Black people even get food allergies. She now runs a program called Compassion 4 Anaphylaxis to educate communities of color on the subject.

“People need to see people and resources that look like them, that live like them, that speak to the culture in which they live,” she said.

Mahdavinia, the allergy expert at Rush, noted that food allergies are all about education.

“Food allergies are an unpredictable disease,” she said. “We really don’t know when a very bad reaction is going to happen. It’s about avoidance and what to do when a reaction happens.”

About nine years ago, Kamisha York was taking her son to a doctor’s appointment in Austin, Texas – with her two other children in tow – when the unpredictable happened. York was eating cashews and gave a small piece to her 3-year-old daughter, Peyton.

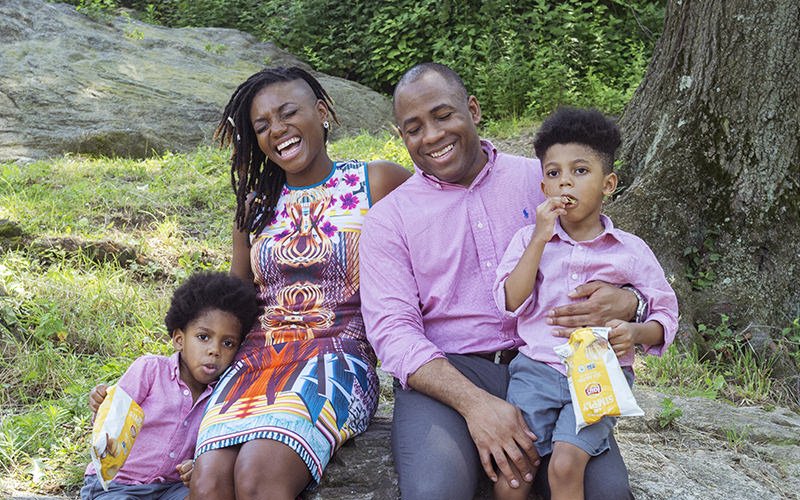

Kamisha York, pictured with her daughter, Peyton, and other family members, started Peyton’s Allergy Shield of Hope last year to support families struggling with food allergies. (Photo by Lynn Walker Photography)

After arriving at the doctor’s, Peyton was coughing, wheezing and scratching, with blisters developing all over her body.

“Thank God we were in front of the doctor’s office when it’s going down, because I didn’t know what an anaphylaxis reaction looked like,” she said.

Although she had private insurance, York was shocked to discover it did not cover EpiPen, the brand name of epinephrine auto-injectors used to neutralize anaphylactic reactions. An EpiPen kit can cost $700 or more.

As York and her family learned to live with Peyton’s allergies, grocery store trips became longer and more expensive. But through years of trial and error, the family was able to figure it out.

Today, York offers guidance to anyone who needs it. She was in the process of getting her own nonprofit off the ground when the COVID-19 pandemic put the world on pause.

Thomas and Dina Silvera were encouraged this summer as Americans developed a renewed interest in racial disparities after the killing of George Floyd in late May, and they’re hopeful people will start paying more attention to health disparities as well.

Their efforts have paid off in New York: A year ago, Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed Elijah’s Law, which requires day care providers to follow new guidelines to prevent and respond to anaphylactic reactions.

“There is a big problem when it comes to health in the Black and Hispanic communities,” Thomas Silvera said. “It’s unfortunate that we had to have a whole systemic racism uprising in the past couple months in order to put the spotlight on it.”