PHOENIX – They’re often labeled the “model minority,” a misconception surrounding the nation’s 20 million Asian Americans that assumes financial stability, high levels of education and better health across the board.

But experts say that myth can mask higher rates of some chronic illnesses and hinder efforts to improve early detection and treatment of certain conditions.

Cronkite News spoke with experts across the U.S. about these health disparities, as well as efforts to overcome them and help Asian Americans get the health care they need. The responses offer a glimpse into some of the challenges facing this very diverse community – and what researchers are doing to identify and address those obstacles.

What should we know before discussing these health disparities?

Dr. Manasi Jayaprakash of the Asian Health Coalition in Chicago said one of the biggest challenges in identifying disparities among Asian Americans is that too often data and research focus on this demographic as a monolith.

“It’s very important for us to look at data by different subgroups: Koreans versus Vietnamese versus Chinese versus South Asians,” Jayaprakash said, “because that gives us a very different picture for health disparities.”

With cancer, for example, mortality rates overall in Asians are lower when compared with those of whites. But, Jayaprakash noted, “within the Asian group there are a lot of differences.”

Using grant funding, her organization partners with community groups on the ground to help bridge language and cultural barriers to “ensure representation of the different Asian subgroups in various facets of research.”

With more specific data, Jayaprakash said, organizations can develop “better, targeted approaches to addressing problems.”

A study published earlier this year in the American Journal of Public Health used California health data to assess disparities among Asian Americans and found that as an aggregate, Asians seemed healthier than whites. Each subgroup, however, had at least one identified disparity “disguised by aggregation.”

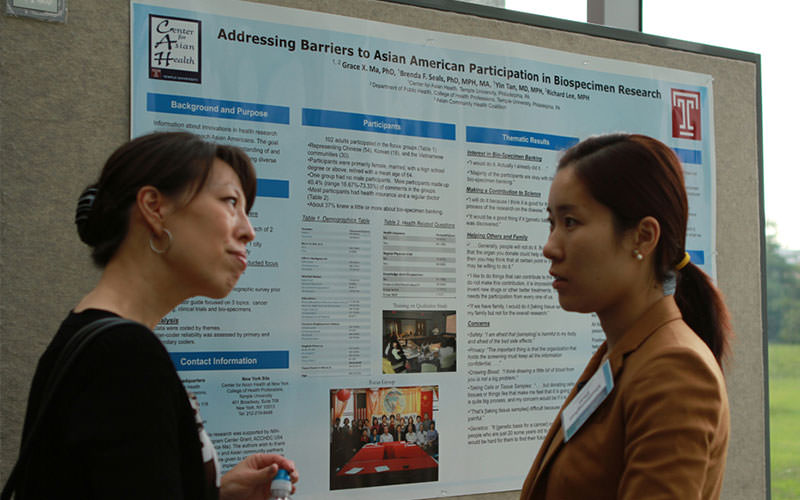

The Center for Asian Health at Temple University in Philadelphia is one of several entities nationwide working to identify and improve health disparities among Asian Americans. Federal statistics show Asian Americans are most at risk for cancer, heart disease, diabetes and conditions including hepatitis B and liver disease. (Photo courtesy of Center for Asian Health)

What are some of the largest health disparities among Asian Americans?

According to the federal Office of Minority Health, Asian Americans are most at risk for cancer, heart disease, diabetes and conditions including hepatitis B and liver disease.

Cancer, in particular, stands out.

“Asian Americans have a lower incidence and mortality than non-Hispanic whites in all cancers combined but higher rates for certain cancers – especially liver and stomach cancer,” said Laura Makaroff, senior vice president for prevention and early detection at the American Cancer Society.

Among Asian Americans, Makaroff said, an estimated 1,700 men and 800 women will be diagnosed with liver cancer every year – about twice as many as whites.

Liver cancer is the second-leading cause of cancer death among Asian American men and fifth for Asian American women, and the rates are “particularly elevated in Laotians, Vietnamese and Cambodians, likely due to recent immigration as well as a high prevalence of hepatitis B infection in their countries of origin,” Makaroff said.

Asian Americans also suffer from stomach cancer at rates twice as high as whites, with an estimated 980 men and 820 women diagnosed each year, Makaroff said. Stomach cancer is especially high in Koreans, largely due to a prevalence of H. pylori, a type of bacteria that can cause ulcers in the stomach lining or small intestine.

The good news is that stomach cancer rates overall have been declining, Makaroff said, thanks to such preventive steps as eating “more fresh fruits and vegetables, lower consumption of salt-preserved foods and a reduced prevalence of the H. pylori infection through improved sanitation and antibiotic treatment.”

What else can be done to help prevent these medical conditions?

Earlier testing and cancer screenings lead to treatments that could help reduce some of these disparities, the experts said, but they also noted that cancer screening rates are lowest among Asian Americans.

“There are a lot of preventable deaths that are happening in cancer because the screening among all the Asian groups is much lower … for breast cancer, cervical cancer, colorectal cancer – all of the cancers that have screenings associated with them,” Jayaprakash said.

Dr. Grace X. Ma, director of the Center for Asian Health at Temple University in Philadelphia, said culture may play a part in those lower screening rates.

“If you look at China and the people who are born there,” Ma said, “their screening guideline is very different from American cancer screening.”

For example, she said, women living in the U.S. are educated to get mammograms once they reach a certain age to help detect breast cancer, but in China, mammography is used for diagnoses rather than early detection or regular screening.

Although there are no recommended screenings for stomach or liver cancer, other steps could be taken to reduce cases in Asian Americans. Doctors can test for the H. pylori bacteria that can cause stomach cancer, and antibiotics can kill the bacteria if found early enough.

As for liver cancer, the most common risk factor is chronic infection with hepatitis B or C. There is a vaccine for hepatitis B, but there’s no cure once someone’s infected.

Because of that, Yicklun Mo, who works with Jayaprakash at the Asian Health Coalition, stressed the importance of getting tested to know one’s status. It’s especially vital that pregnant women get tested because they can pass the infection to their babies at birth. If the mother’s infection is known, vaccinations can prevent her child from getting infected.

Mo called the hepatitis virus a silent killer.

“You don’t get tested, you never know,” he said, “so you can easily transmit it to your partners and also in childbirth.”

Through a grant from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Asian Health Coalition runs a program to increase screening and either vaccinations or appropriate care for hepatitis B.

With cancer screenings, Jayaprakash said rates among Asian Americans overall are at about 40%. The goal is to double that. “So we have a long way to go,” she said.

What are some other factors influencing these disparities?

There is no doubt that language barriers are an obstacle for Asian Americans seeking health care. The Office of Minority Health notes the percentage of persons 5 years or older who do not speak English very well varies among Asian American groups: 48.9% of Vietnamese, 44.8% of Chinese, 20.9% of Filipinos and 18.7% of Asian Indians are not fluent in English.

“There are many foreign-born Asian Americans that have limited English proficiency. So getting access to care oftentimes is quite challenging,” Ma said. “Especially now with COVID, if they’re not sick or having severe symptoms, they try to avoid it.

“We need to understand our population and the multifaceted barriers they’re facing. The solutions have to be culturally, linguistically appropriate.”

Stigma may also play a role, especially in seeking help for mental health conditions.

“A lot of Asian Americans also have mental illness, but they are three times less likely to seek treatment,” said Mo at the Asian Health Coalition. “There’s a lot of reasons behind that: Part of it stigma, part of it language issue, part of it they are not aware of some of the services.”

Makaroff said lifestyle choices also make a big difference in overcoming some of these disparities.

“Individual choices about maintaining a healthy body weight, staying physically active, eating a healthy diet, avoiding tobacco, limiting or avoiding alcohol – all super important,” she said.

“But it’s really important to recognize that not every individual has the same access to those kind of healthy choices. So community action, like policies and environments that support healthy lifestyles, are really critically important, too.”

Earlier testing and cancer screenings lead to treatments that could help reduce some of the disparities seen in Asian Americans, who, for example, suffer from stomach cancer at rates twice as high as whites, but experts note that cancer screening rates are lowest in this community. (Photo courtesy of National Cancer Institute)

What’s being done to make improvements?

Mo said the Asian Health Coalition has aimed to reduce such disparities for more than 20 years. The group works with some two dozen community-based organizations to develop and implement culturally and linguistically appropriate health initiatives.

“People in their own community, they speak their own language, they understand their culture,” Mo said, and so those grassroots groups help the coalition disseminate information.

“They also help us to implement the program, bring us data back and then we will be able to analyze it, be able to understand that this intervention really worked with this population, this intervention did not work so well.”

Whether these disparities carry over into the next generation of Asian American remains to be seen, said Ma at Temple. The next generation may be more integrated and assimilated into society, but “they also encounter many other disparities,” she said.

“They are still considered a minority. Oftentimes, they are encountering discrimination or prejudice, and that could cause stress and stress could cause a physical problem.”

Makaroff said culturally appropriate programs are vital to addressing all of this.

“To make a big difference and seriously impact and reduce health inequities in Asian American populations … we need to address language access, be culturally competent, really support and engage partnerships and collaborations, include communities and people in all of research, and really be responsive and accountable to all of the different Asian American communities that we serve,” she said.

“We need to begin and end with the community.”