Fentanyl patches can be prescribed by doctors for patients experiencing intense pain. (Photo by Alcibiades via WikiMedia Commons)

TUCSON – Pima County’s Medical Examiner reported 17 fentanyl-related deaths last year, up from seven in 2014 – a deadly trend involving one of the most potent synthetic opioids in the world.

“The fentanyl compounds seem to be what’s new and interesting,” said Dr. Greg Hess, Pima County’s chief medical examiner.

Fentanyl is a drug the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration warns is 30 to 50 times more powerful than heroin. Authorities seized an estimated 58 pounds of fentanyl or fentanyl-related compounds across the state over the last ten months, Arizona DEA spokesperson Erica Curry said.

The drug is showing up laced in heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine and even in counterfeit pain pills. Earlier this year, medical examiners in Minnesota reported fentanyl toxicity as the cause of the singer Prince’s death.

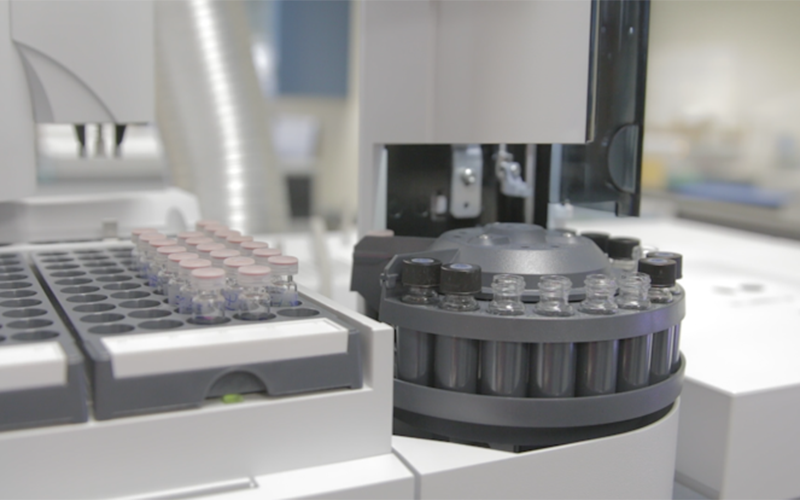

Vials in a machine at the Arizona Department of Public Safety’s crime lab, where fentanyl can be tested. (Photo by Lily Altavena/Cronkite News)

Cronkite News reviewed more than a dozen autopsies conducted by Pima County’s Medical Examiner over the past year-and-a-half that involved fentanyl. The deceased included a 19-year-old man who died from an oxycodone and fentanyl overdose, a 34-year-old inmate found on his bunk with a homemade syringe by his body and a 41-year-old woman, found dead with a needle still in her arm. In the majority of cases, other drugs like methamphetamine and cocaine showed up on toxicology reports in addition to the synthetic opioid.

Related video:

Fentanyl provides an “extra kick”, Curry said, especially for addicts who have built up a tolerance for drugs like heroin. Measured in micrograms, a lethal dose of the drug can be as small as two or three grains of salt.

“We have seen a lot of cases where people took a drug–a white powdery substance–thinking that it was something else when in reality it was pure Fentanyl and they’ve overdosed from that,” Curry said.

In July, the DEA issued a nationwide warning about counterfeit prescription pills containing fentanyl. The agency reported that “hundreds of thousands of counterfeit prescription pills, some containing deadly amounts of fentanyl have been introduced in the U.S. drug markets.”

Lt. James Scott, of the Tucson Police Department’s Counter Narcotics Alliance, said the counterfeit pills are convincing imitations.

“They’re popping up all over town now,” he said. “They look just like regular morphine pills or oxycodone pills, but the difference is they got a small amount of fentanyl in them and some other type of agent that they cut in there.”

Pills laced with fentanyl and heroin. Overdose deaths in Pima County involving fentanyl also typically involved another drug. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration)

Stuart, a nurse anesthetist who asked Cronkite News not to use his last name, said he was “squeaky clean,” never smoked, never drank alcohol and never did drugs. Until the day he shot himself up with Fentanyl.

“The heavens parted, the angels sang, those temporary problems that I was facing went away and just for a few minutes, you know, life was okay again,” he said.

Working 70 and 90-hours a week, he said he wanted to know what patients experience after receiving the drug, typically used for patients in extreme pain.

For Stuart, fentanyl was a routine part of his job administering anesthesia. A 2006 study from the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists found that opiates were the number one substance misused by certified registered nurse anesthetists.

While doctors and nurses spend a lot of time around powerful substances like fentanyl, the 37-year-old remembers few warnings about addiction.

“The only time I remember it was talked about was when I was in anesthesia school and we had that lecture on it,” he said. “It’s definitely something that isn’t talked about enough.”

His addiction came crashing down on him in January of last year when his employer asked him to take a drug test. Sitting in the testing lab, Stuart called his wife and told her for the first time that he had been using fentanyl. Not long after, he checked himself into a 90-day rehab program.

Stuart, who asked Cronkite News to use his first name only, with his family. The nurse anesthetist struggled with a fentanyl addiction. (Photo courtesy of Stuart)

“Very quickly, things started to escalate and I started to ask myself, ‘What in the world am I doing? I have to stop doing this,'” he said. “But by then, the addiction was already in full force and at that point, as bad as I wanted to stop, my body had become addicted to it.”

Stuart said he disclosed his addiction to the Arizona State Board of Nursing and was allowed to enroll in a program for nurses recovering from substance abuse. To keep his license, there are stipulations: Every morning he logs into a program that randomly decides if he will be drug tested that day — on his own dime. He also attends AA meetings a few times a week.

“How do you explain that to your kids that, you know, ‘Hey dad lost his job because dad was taking a needle and shooting medication into his arm?'”

Stuart worries about the stigma opioid addiction carries.

“No matter how you feel, no matter how bad your depression is, no matter how bad you think your situation is there is hope,” Stuart said. “And part of that is reaching out and trying to get help.”

Number of overdose related deaths increasing

Number of overdose related deaths increasing