SILVER CITY, N.M. – Silver City, a small town in southwestern New Mexico, preserved its mining character and stands unbothered by modernity and commercialization. The town’s hilly streets introduce visitors to its quiet beauty. Everything whispers a story, such as the nearly 150-year-old Palace Hotel, with a mine entrance in its basement.

North of the town’s many Victorian, Spanish Colonial and American Western-style homes – some more, some less elaborate – Silver City is a gateway to the mountainous region of a vast Gila National Forest, home to the world’s first designated wilderness area.

The Gila Wilderness, defined in the Wilderness Act of 1964 as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain,” celebrated its 100 anniversary.

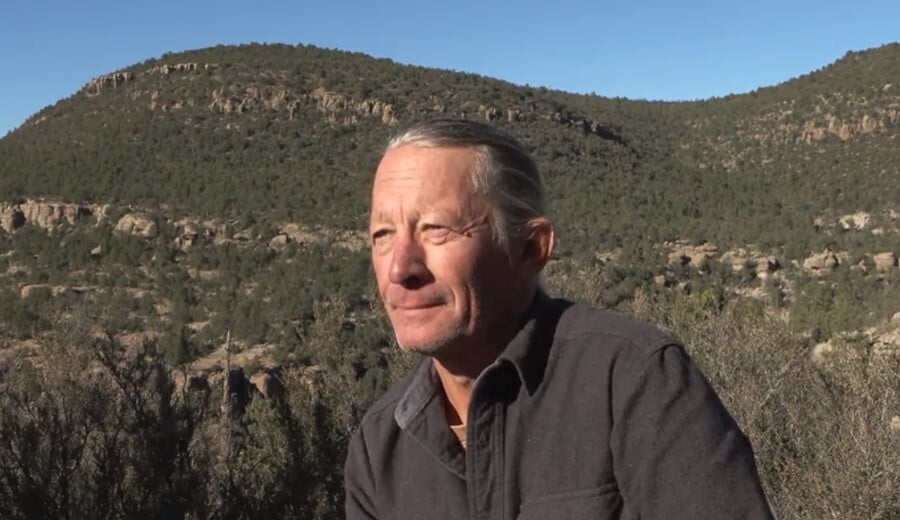

“In layman’s terms, (the wilderness) stays wild and pure, as it was intended, as it started out, before we even came here,” said Brett Myrick, a Navy SEAL veteran from Silver City. “I worked wilderness trails for the Forest Service, and as a wilderness trails technician, we don’t take a wheel into the wilderness. We don’t take a chainsaw to clear the trees. We go in with crosscut saws, like from the late 1800s. No noise, no fumes. It’s a place of quiet, a place of solitude.”

But this harmony, quiet, solitude and even public health are now under threat.

The Department of the Air Force wants to change how low, how fast, how often and at what time military aircraft can fly, what the planes can release and in what quantities.

Brett Myrick center first row during his time as a Navy SEAL. (Photo courtesy of Brett Myrick)

“The Air Force is proposing to turn giant swaths of southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico into low-level military operations training area,” said Allyson Siwik, executive director of the Gila Conservation Coalition.

The 212-page Draft of the Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) includes requests for supersonic (faster than the speed of sound) flights at lower altitudes to accommodate the military’s growing need for training at three Arizona bases: Davis-Monthan Air Force, Luke Air Force and Morris Air National Guard.

The Air Force and Luke Air Force Base did not respond to requests for comment from Cronkite News.

Military jets that fly faster than the speed of sound produce sonic booms, which the human ear interprets as an explosion or a loud thunder.

Silver City is the county seat of Grant County the entire county will be affected by these test flights. Some residents have experience with previous Air Force training flights.

“When it flew over my house, it shook the windows, and it’ll shake a building. It’ll break windows,” said retired Vietnam veteran Arthur Ratcliffe, referring to low-altitude military training flights over Grant County, New Mexico.

Myrick also experienced a scare set off by an aircraft flying over the Gila Wilderness. “The explosion of sound that blasted down into the canyon where I was, I went to the ground. It scared me and animals in the area, and the concussion from the sound of that aircraft flying over actually even created rockfall,” Myrick said.

Arthur Ratcliffe during his time in the military. (Photo courtesy of Arthur Ratcliffe)

The veteran said the sudden sound of the military aircraft flying close to the ground would be triggering for any service member. “That plane flying over me in the Middle Fork still sits with me today. It’s a memory that I don’t want to have,” Myrick said.

Ratcliffe, who moved to the Silver City area for its peaceful nature, joined other community members to voice his concerns over the proposed changes. “(Sonic boom) triggers my PTS (post-traumatic syndrome) symptoms, creates great anxiety … I have had several panic attacks as the result of loud noises, explosions.”

While military aircraft have trained at supersonic speeds before, the changes would lower the flight floor in five Military Operations Areas (MOAs) designated for military training airspace. In three MOAs the floor will be lowered to 500 feet, while in two others, it will be lowered to 100 feet above the ground.

“That is essentially like having warfare games literally above your head, and so we are very concerned about those areas being used as sacrifice zones,” said Patrice Mutchnick, director of the educational nonprofit Heart of the Gila.

U.S. Rep. Gabe Vasquez (D-New Mexico) released a letter opposing the expansion expressing concerns over increased noise pollution and threats to the environment and tourism. A letter from Arizona Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D-Arizona) cites a lack of transparency and community engagement underlining insufficient public hearing and ignored Freedom of Information Act requests.

The Tohono O’odham Nation, the San Carlos Apache and the White Mountain Apache tribes will also be impacted by the proposed changes. Both the Tohono O’odham Nation and San Carlos Apache Tribe submitted public comments criticizing DEIS for inadequately addressing the proposals’ negative effect on the tribal communities and failure to meaningfully consult the tribe.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently examined the DEIS, highlighting public health concerns such as inadequate investigation of sleep disturbances, the possibility of hearing loss, the “surprise factor” of low-level and supersonic flights and a lack of investigation of overall health impacts of noise exposure.

Allyson Siwik speaks on Nov. 12, 2024, about the various environmental and health concerns from the proposed Air Force modifications to southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. (Photo by Ignacio Ventura/Cronkite News)

Those who will be affected if the proposals go through agree with the EPA that the Air Force failed to investigate all possible health effects thoroughly.

“(DEIS) noise analysis pretty much says that it’s just too hard to assess the impacts of noise. We can’t do it. … They have a responsibility to assess those impacts, and it can be done,” said Siwik, who is also a member of Peaceful Gila Skies, an initiative formed in 2017 to successfully oppose Holloman Air Force Base proposal to expand military training over the Gila region. Together with Peaceful Chiricahua Skies, the two groups collected over 900 signatures to halt the modifications over the Gila Wilderness, rural communities and tribal lands.

Earlier this year, a group of scientists published their findings in the Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology revealing that military aircraft noise near Naval Air Station Whidbey Island north of Seattle was exceeding federal regulations and putting the health of the studied population at a substantial risk. That included degraded sleep and learning delays in school-aged children.

“The thought of military fighter jet aircraft flying at supersonic speeds and releasing magnesium flares and chaff over a pristine wilderness is an abomination to the sanctity of wilderness,” Myrick said, voicing community and wilderness preservationists’ other two major concern: flares that are released during maneuvering and that can ignite wildfires and chaff, or aluminum-coated silica fibers used to confuse enemy radar systems. The Air Force’s proposed changes include authorization to use chaff and lowering the release altitude for flares.

Chaff contains per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), dubbed “forever chemicals” because they do not break down. PFAS can leak into drinking water, soil and wildlife, and have been linked to increased risk of cancers, decreased fertility and developmental delays in children, according to the EPA.

After the EPA set new drinking water standards considerably limiting PFAS this year, the limits were challenged by water utilities and chemical manufacturers calling the rule unreasonable in its demands to remove the chemicals from drinking water.

“We support fully our military and the need for fighter pilots to have adequate training,” Siwik said. “We just feel that the Draft Environmental Impact Statement did not adequately defend its purpose and need for this proposed action.”

Navy SEALs veteran Brett Myrick, sitting on the border of the Gila National Forests and Wilderness, discusses his opposition to the proposed Air Force modifications and their implications on Nov. 13, 2024. (Photo by Ignacio Ventura/Cronkite News)

In addition, Siwik and others in the community wonder why the military is not considering alternatives, such as the Barry M. Goldwater Range, a vast military training facility in southwest Arizona. “We are encouraging the Air Force to go back to the drawing board and redo the Draft Environmental Impact Statement.”

Myrick said it’s important to keep the region pristine and protected. If the proposal is approved, “I will actually be forced to sell my place and I would have to move away from here because I will absolutely not be able to stomach those jets flying over this wilderness. … This is my home, fifth generation, and I love this place. So that’s how important it is to me that this does not happen.”