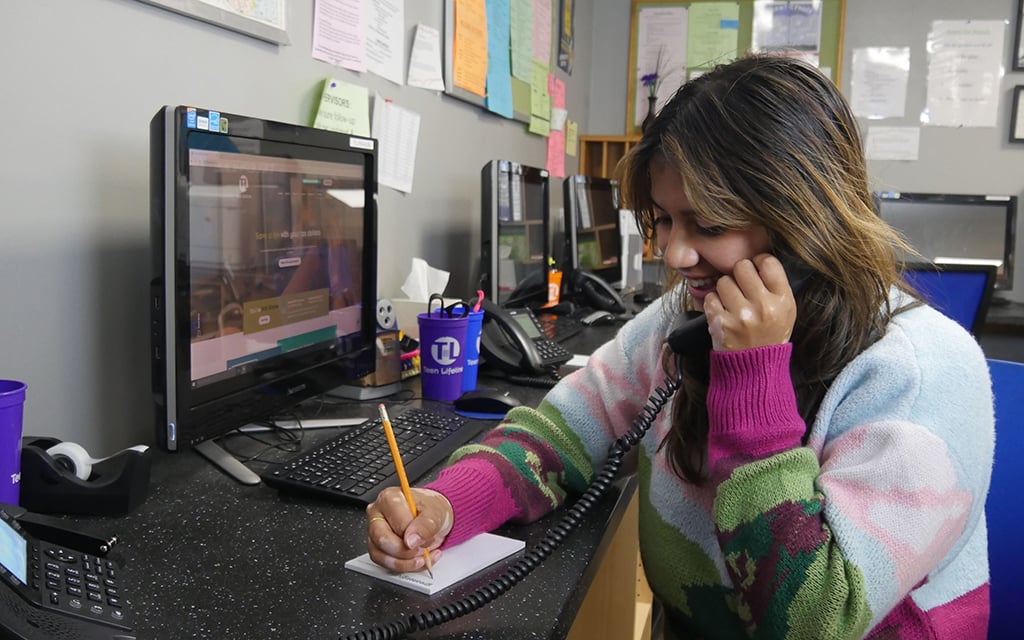

Ria, a peer counselor at Teen Lifeline, takes a call from another teen at the hotline’s office. (Photo courtesy of Teen Lifeline)

Soham, a peer counselor at Teen Lifeline, takes a call from another teen at the hotline’s office. (Photo courtesy of Teen Lifeline)

PHOENIX – Suicide rates for young Americans are rising. With Latino youth among the most vulnerable, some researchers are calling for a culturally informed approach in therapies.

In ethnic communities family, culture and societal expectations significantly affect identity and mental health. Dr. Yovanska Duarté-Vélez, associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University, developed the first culturally adapted treatment for suicidal Latino and Hispanic teens.

“Part of the development of adolescents, identity is essential component in which we take into consideration different aspects of the self, like their ethnicity, their cultural values, their beliefs and how they see themselves and see their families,” Duarté-Vélez said.

Imagine an onion, said the researcher, who has written extensively about ethnically diverse teens with suicidal thoughts and ways to tailor treatments to them. In the onion, “the youth is in the center and is surrounded by the family, the context, like the environment, and then the broader cultural values and system,” Duarté-Vélez said.

Duarté-Vélez’s Socio-Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Suicidal Behaviors (SCBT-SB) considers each layer of the onion. It builds off traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), focusing not only on coping with and changing negative thoughts and attitudes but also incorporating how family communication, social interactions, trauma, activities and substance use can influence those thoughts and behaviors.

During a recent trial of a small sample of 46 Hispanic/Latino youths and at least one of their caregivers, the results revealed the therapy was more effective in reducing suicide attempts and depressive symptoms when compared to regular therapies. “There may be other clinicians that … take into consideration cultural aspects – and that’s great – but … we need to make sure that the protocol we are testing is included in a standardized way,” Duarté-Vélez said.

Delivering quality care to a rapidly diversifying population has been challenging for the health-care system. While no laws mandate culturally adjusted therapies from every provider, some recent federal initiatives target cultural competency.

Kelly Zaragoza, a Phoenix-based Latina counselor, mainly practices CBT but emphasizes the importance of culture and identity when working with a client. (Photo courtesy of Kelly Zarazoga)

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded the list of those whom the Medicare Advantage plan has to provide services tailored to diverse cultural needs. The list includes ethnic, cultural, racial and religious minorities; people with limited English proficiency; LGBTQ+; rural residents; and others who are affected by inequality. In addition, optional disclosure of the providers’ cultural and linguistic knowledge and experience now must be clearly stated in the directories.

Cultural competency in health care does not have a legal definition. Still, under Title IV of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, its absence can be seen as a form of discrimination based on national origin. The term has a variety of interpretations: The American Hospital Association defines cultural competence as the ability to provide personalized care to patients with diverse values, beliefs and behaviors.

Other federal laws and policies protecting nondiscrimination in health care are Section 1557 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act. ACOM 405 “Cultural Competency and Family Member Center Care” in the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS) mandates providers to follow cultural competency standards that align with federal regulations.

Some practitioners say that proper therapy incorporates this cultural sensitivity by default. Kelly Zaragoza, a Phoenix-based Latina counselor, mainly practices CBT, a standard type of therapy, but emphasizes the importance of culture and identity when working with a client.

“I would hope that most therapists …(have) the cultural competency to understand that we need to incorporate family members,” Zaragoza said. “Understanding the … cultural biases that they might experience, the gender roles that might exist.”

Almost half of Latino adults living in the U.S. are born in another country. After Puerto Rico, the Southwest has the highest concentration of Hispanic population by proportion, and almost half of all Arizona k-12 students are Latinos. Zaragoza said it is crucial to factor in identity and lived experiences: “The acculturation pieces of it, the assimilation, depending on are they first generation … having those conversations and giving them the space to talk about what that looks like for their lives.”

Cynthia Ramos, a Scottsdale-based, bilingual Hispanic therapist, employs cultural sensitivity through a type of therapy called Acceptance and Commitment, emphasizing to her young Latino clients the importance of accepting their values without labeling them. Ramos said therapies based on Western values of individualism might resonate less with Latino caregivers who prioritize cooperation and interdependence.

Cynthia Ramos, a Scottsdale-based, bilingual Hispanic therapist, says therapies based on Western values of individualism might resonate less with Latino caregivers who prioritize cooperation and interdependence. (Photo courtesy of Cynthia Ramos)

“There are no good or bad values. We don’t categorize them. … We have pride and respect for elders, family collectiveness, right? And those values can be accepted as well as individual values,” Ramos said. “Sometimes that can produce some tension, especially for Gen X.”

Duarté-Vélez said that second-generation Latinos often grow up with their feet in two worlds: “(They have) the Latino perspective, and then they go to the school and have a more Americanized way of seeing the world. So that may be a little more challenging as clinicians to help (youths and their caregivers) navigate those differences and understand each other.”

Both Ramos and Duarté-Vélez call family involvement in culturally relevant interventions critical. “Adolescents are building their identity and their autonomy, and that’s normal development,” Ramos said. “So (we) help give parents that psychoeducation … to facilitate communication, help reduce the conflict and help them understand each other, build that supportive environment for that teen.”

More profound obstacles arise when families consider mental health only a private affair. This might contribute to higher rates of depression and suicidal tendencies among youths.

“Even being a Latina provider … it makes me really anxious sometimes to go up in front of community members and talk to them about mental health because I know that there’s a stigma (that) still exists out there,” Zaragoza said.

In her trials, Duarté-Vélez saw higher engagement and attributed it to a different phase of the crisis.

“When we get families on this model, they already had a suicidal crisis, and … whatever they were doing was not working,” Duarté-Vélez said. “Then they see we are Latino clinicians, we share some of the same values, we speak the language. So one way of addressing mental health stigma is showing (families) we are here to support and respect them.”

A family’s rejection of their teen’s identity can also hinder therapy and stagnate healing for a young adult and the caregivers. This is especially true for LGBTQ+ teenagers, who often feel repressed by the expectations of their families. A 2023 survey from The Trevor Project showed that among LGBTQ+ Latino teens and young adults, 42% considered suicide and 15% attempted it.

Therapist Cynthia Ramos’ office in Scottsdale. “I have worked in many different settings and there have been (some) in which there was a lack of cultural sensitivity and awareness,” Ramos says. (Photo courtesy of Cynthia Ramos)

“Over years of working with this community, we have seen that it is harder to engage cisgender boys in treatment (and) they’re more reluctant to see the usefulness of being in therapy,” Duarté-Vélez said. “Girls are more encouraged to identify their feelings and talk about what bothers them (so) they are easier to engage. It’s harder to engage with trans youth overall. The major challenge here is working with the dynamics of the families, (others) accepting their identities, and working with social rejection.”

After receiving an American Suicide Prevention Foundation grant in 2023, Duarté-Vélez will begin the largest trial of culturally informed therapy for Latinos so far. In partnership with the National Institute of Mental Health at a hospital in Mexico City, it will include 114 participants.

This trial will involve community health workers to test how the environment and other social factors affect mental health.

“Community health workers support families on what we call social determinants of health: food, transportation, living situation, job, learning the language and different social aspects,” Duarté-Vélez said. “We believe families have needs that go beyond what is done through therapy, but … you need to test it to know.”

While SCBT-SB is not yet widely integrated into mental health practices, more researchers, therapists and counselors emphasize the importance of deeper cultural awareness and more granular approach in psychotherapy.

“I have worked in many different settings and there have been (some) in which there was a lack of cultural sensitivity and awareness,” Ramos said. “(Awareness) doesn’t mean you have to know everything about every culture, but it does mean that you approach it with caution and more curiosity and kind of a humble heart.”