WASHINGTON – Survivors of nuclear testing and uranium mines are ramping up pressure on Congress to reauthorize a federal compensation program that expired in June.

Many of those afflicted since World War II are from the Navajo Nation, which is organizing a rally next week that will include prayers at the Capitol for radiation victims.

“I want Congress to realize that it’s important and we need to pass this bill because some people did not get any … compensation,” said Maggie Billiman, whose father, a Navajo Code Talker during World War II, died of stomach cancer that she attributes to fallout from nuclear tests that settled over their hometown in Arizona.

Much of her family has suffered from cancer, she said, and she looks forward to the ceremonial performances and prayers when activists converge at the Capitol on Sept. 24.

“That’s why we’re doing a peaceful rally there – to bring people and be able to pray and sing and if someone could hear our voices,” Billiman said. “It’s hard to process all these things and to have my family be suffering and my community be suffering.”

The federal government has paid $2.6 billion to over 41,000 downwinders and uranium workers since 1992 under the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act.

The program provides $50,000 to $100,000 to people who developed certain illnesses linked to radiation and lived in a fallout zone or worked at uranium mines and mills.

In March, the U.S. Justice Department projected that another 1,070 claims would be approved by the end of September.

Congress has repeatedly extended the program. The most recent extension expired in June.

The Democrat-controlled Senate voted 69-30 in March to extend the filing period for five years.

The House, controlled by Republicans, has yet to vote on the measure. Speaker Mike Johnson has not said whether or when he would put the RECA reauthorization to a vote. Aides ignored requests Monday to discuss the bill.

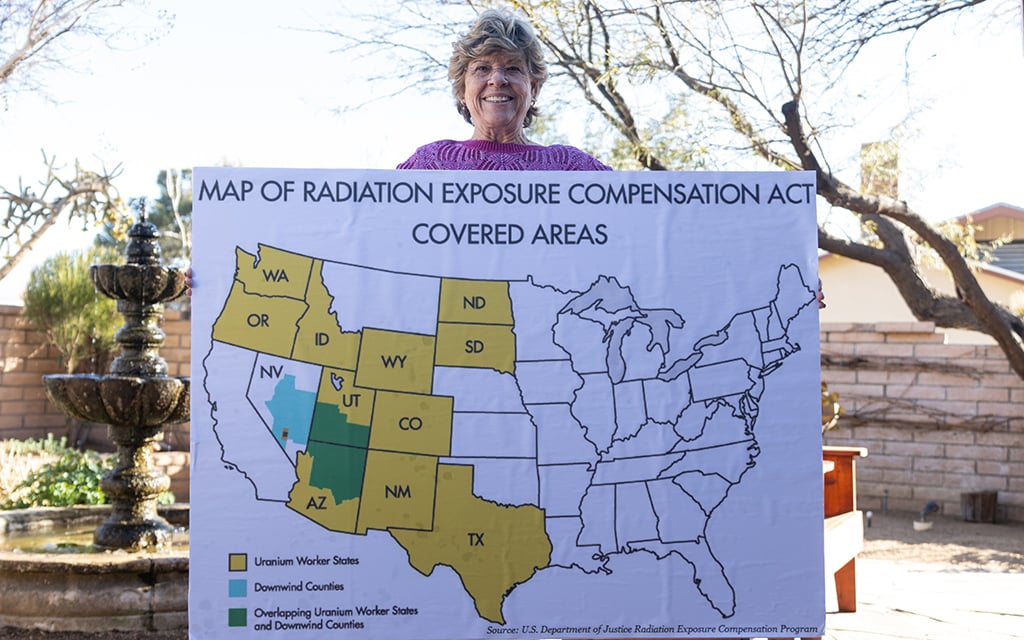

Jean Bishop, a Mohave County supervisor, shows a map of the radiation-exposed areas during a conversation on Feb. 3, 2022, in Kingman. (File photo by Monserrat Apud/Cronkite News)

“Republicans are refusing to take up the issue because it’s going to cost money,” said Navajo Larry King, a former uranium mine worker from New Mexico.

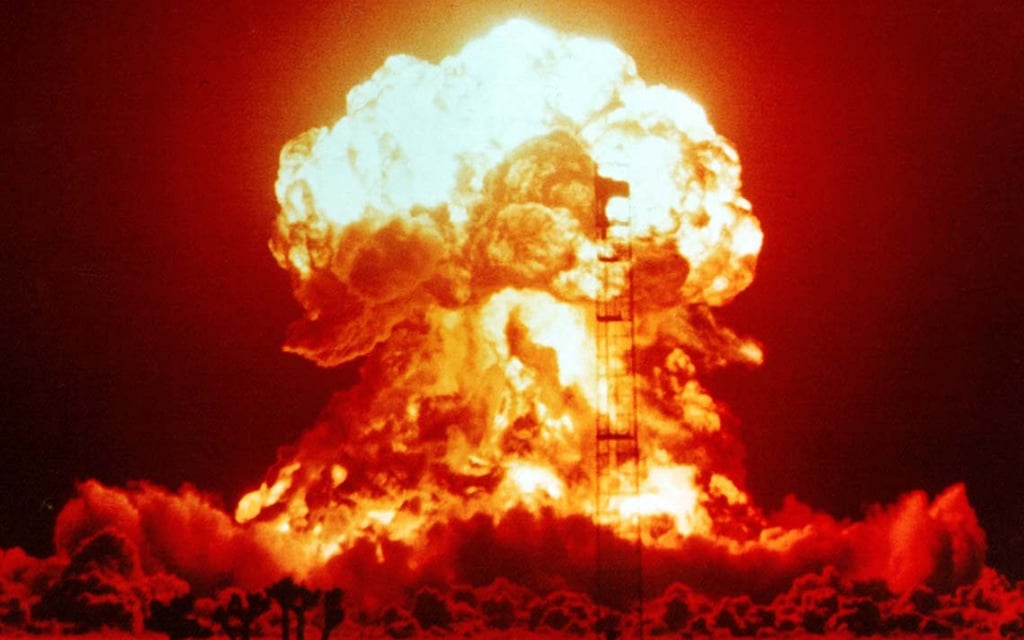

Many Diné lived downwind of nuclear bomb tests the U.S. government began conducting during World War II. An estimated 3,000 to 5,000 worked in the mines that operated for decades, living nearby with their families.

The current federal budget runs out on Sept. 30. But RECA payments come from a trust fund that don’t require any immediate replenishment, according to the Department of Justice

“Our people are neither expendable nor invisible,” Justin Ahasteen, who heads the Navajo Nation Washington Office, said in a statement.

Advocates will take buses from Albuquerque, New Mexico, to the nation’s capital, a two-day trip. Organizers expect more than 70 people at the protest.

The DinéTah Navajo Dancers will perform and provide blessings on the Capitol lawn to those affected by radiation exposure.

Although the Navajo Nation is a key advocate for RECA, the program applies to downwinders in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Guam.

About one in seven approved claims – 5,480 through the end of 2023 – came from Native Americans, 86% of them Navajo, totalling $372.6 million.

King said he believes opponents in Congress are under a misunderstanding that this an “Indigenous bill.”

“It’s for everybody. It’s to compensate former uranium workers of all walks of life. Not just Indigenous people,” said King, 67, a resident of Church Rock, New Mexico, who spent eight years as a mine worker.

“Speaker Johnson needs to get off his high horse and put that legislation up for discussion and a vote.”