WASHINGTON – Police and firefighters in Arizona who suffer from PTSD could soon use workers’ compensation to cover therapy that involves the psychedelic drug commonly known as ecstasy or molly.

That depends on the Food and Drug Administration, which plans to vote next month on approval of MDMA-assisted therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder.

An FDA advisory committee recommended against approval on June 4. But advocates remain hopeful.

“The question is, will it be August or will it be two to five years from now? It’s up to the FDA how many people die before it’s approved,” said Jonathan Lubecky, a military veteran who took part in a clinical trial a decade ago and now advocates for its wider use.

Given the depression and suicidal thoughts that too often stem from PTSD, he said in an interview, it’s “ludicrous” to keep MDMA away from patients.

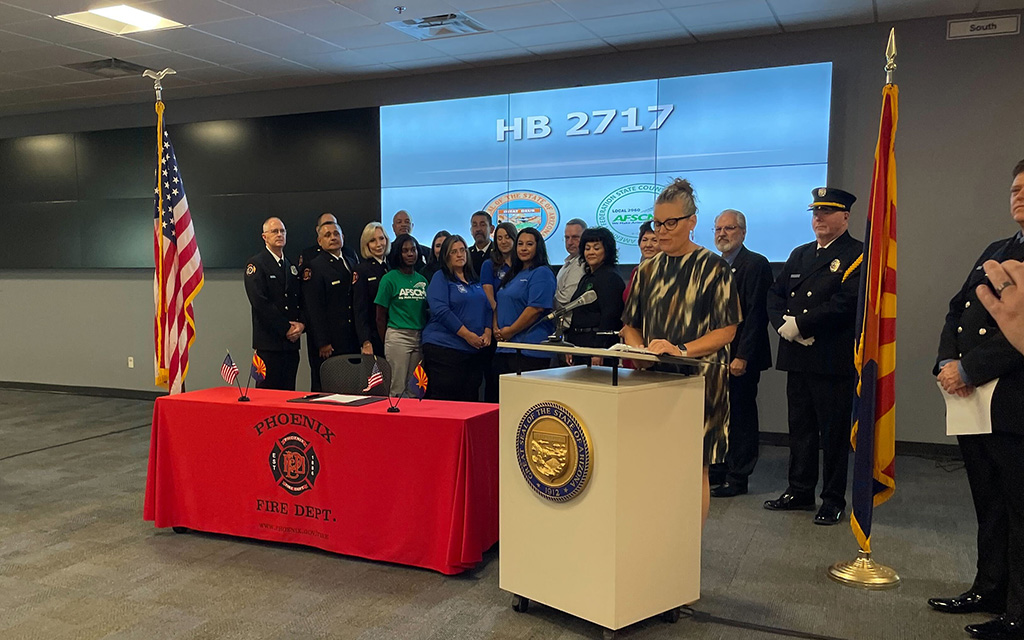

Pending FDA approval, the Arizona Legislature added MDMA-assisted therapy to the list of treatments available to first responders with PTSD under the state’s workers’ comp plan.

Gov. Katie Hobbs signed the measure last month.

MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine) is a synthetic substance that acts as both a stimulant and a hallucinogenic, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration. In the treatment context, it is meant to be used with talk therapy.

The drug increases the patient’s self-awareness and tolerance for revisiting distressing experiences, leading to introspection and reflection, according to Lykos Therapeutics, which submitted the new drug application for MDMA-assisted therapy to the FDA in December.

Two clinical trials were included in the application. At the end of the second study, 71% of the MDMA group no longer met the criteria for PTSD, compared to 48% of those who received a placebo.

“It lifts that fog and then they’re able to process more in therapy,” said Stephanie Miller, a clinical therapist who treats patients in Arizona and Texas virtually.

She frequently refers patients for ketamine treatment, another controversial therapy that has gained popularity among first responders in recent years.

While legal for doctors to prescribe, ketamine – a short-acting painkiller that makes people feel detached from their environment and creates mild hallucinations – is not FDA-approved to treat any psychological disorder.

Many of Miller’s clients work in law enforcement and “MDMA and ketamine are the same things they’re arresting people for on the street,” she said. That makes some of them wary even in a controlled environment.

About half of the first responders she treats have received ketamine treatment. These are especially useful therapies for people who find it difficult to let their guard down, in her view.

“When we have assisted therapies like ketamine and MDMA, it kind of cuts to the chase,” she said.

That’s how Lubecky, who lives in Washington, D.C., described his experience.

“I just started talking,” he recounted. “I knew I would be talking about things that happened in Iraq. I ended up talking about every trauma in my life over the three sessions.”

Lubecky had attempted suicide five times and was taking as many as 42 prescription pills each day. For eight years after coming home from Iraq he struggled with severe PTSD symptoms. Then he started the MDMA trial in 2014.

“The Fourth of July before I did the therapy, I was in my closet, wearing my body armor, with my service dog, having flashbacks,” he recalled.

In the decade since the treatment, he said, he’s had no recurrence of PTSD – even during time spent in Ukraine treating injured soldiers a few miles from the front lines.

“MDMA is not a silver bullet,” Lubecky said. “If you’re not doing therapy, then you’re just doing drugs.”

More than 80% of first responders have reported traumatic events on the job, and 10% to 15% have been diagnosed with PTSD, according to a study published by the Nova Southeastern University College of Psychology in 2018.

“We have so much cumulative stress and trauma with the job that everybody gets their turn on the roller coaster,” said Michael Carleton, a retired Tempe police sergeant.

There are currently only two FDA-approved medications for PTSD: sertraline, sold under the brand name Zoloft, and paroxetine, known as Paxil. Both are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, which affect the neurotransmitter serotonin to help regulate mood, anxiety, appetite and sleep.

While relatively effective at alleviating PTSD symptoms, SSRIs don’t directly address the conditioned fear response at the root of the disorder, according to a 2023 review published in the Cureus Journal of Medical Science.

The stigma around PTSD is an obstacle for many first responders who need help.

A 2019 survey University of Phoenix survey conducted by The Harris Poll found that 57% of first responders would expect negative repercussions from their peers or department if they sought counseling.

“Somebody calls 911 and we go run and give help, but we never asked for help,” Carleton said of fellow police.

Undiagnosed or untreated PTSD can be devastating.

Phoenix Police Officer Craig Tiger died by suicide after an incident in which he used deadly force on a man who assaulted him, his partner and others in a park.

In 2018, the Legislature adopted the Officer Craig Tiger Act, which requires Arizona employers to provide counseling to any peace officer or firefighter exposed to a traumatic event on the job.

“That law has done more for removing the stigma from law enforcement and firefighters than anything I’ve seen in the last 25 years,” Carleton said.