WASHINGTON – A federal program to compensate people exposed to fallout from U.S. nuclear testing expired June 10.

The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act has paid out $2.6 billion to over 41,000 people since 1992. In March, the U.S. Justice Department projected that another 1,070 claims would be approved by the end of September.

“Why do we have to beg to pass RECA?” said Maggie Billiman, whose father, a Navajo Code Talker during World War II, died of stomach cancer she attributes to exposure to fallout that affected their hometown in Arizona. “You don’t put a price tag on human life.”

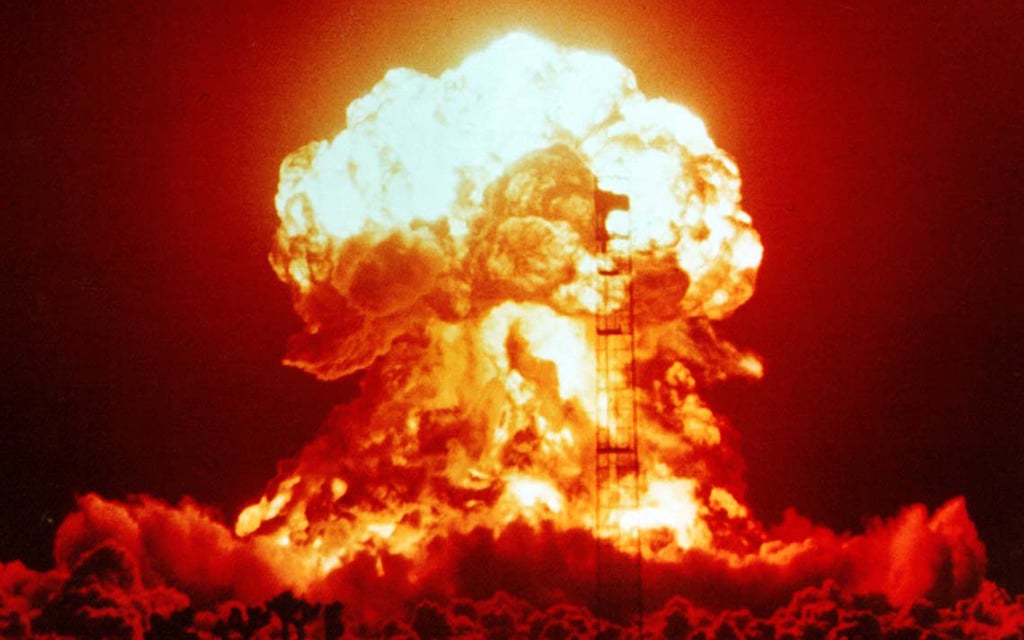

Starting with the Manhattan Project’s Trinity test on July 16, 1945, weeks before bombs destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the U.S. government conducted 94 tests that produced radioactive mushroom clouds in remote areas of the West. Most were over Nevada. One was over New Mexico.

People downwind – including many in Arizona – were exposed to dangerous fallout, typically without warning.

The Billimans’ hometown, Sawmill, on Navajo land, is part of the large affected area where Congress made residents eligible for compensation.

Radioactive particles fell throughout Arizona, according to research from Princeton University’s Program on Science and Global Security. The state’s population grew from about half a million just before World War II to over 1.3 million in the early 1960s.

Congress adopted RECA in 1992 to address claims from downwinders and uranium miners.

The program offers an apology, and lump sum compensation ranging from $50,000 to $100,000 to those who developed certain illnesses linked with radiation exposure, and who either lived in the fallout zones or worked at uranium mines and mills.

The law came in response to lawsuits from uranium workers who accused the government of failing to warn them about radiation hazards.

From 1944 to 1986, nearly 30 million tons of uranium ore was extracted from Navajo lands. The Manhattan Project itself, led by physicist Robert Oppenheimer, was disbanded in 1947, two years after Japan surrendered to end World War II.

An estimated 3,000 to 5,000 Navajo people worked in the mines. They and their families lived nearby.

“The closer you live to mine waste, the higher your risk of chronic metabolic disease,” said Chris Shuey, director of the Uranium Impact Assessment Program at the Southwest Research and Information Center, a nonprofit research and advocacy group. “People who live in these communities next to these wastes, they’re exposed through all of the pathways: air, water, land.”

Claims from Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and Colorado account for $1.8 billion of the payouts under RECA.

Most of the Navajo Nation was covered due to potential fallout. About one in seven approved claims – 5,480 through the end of 2023 – have come from Native Americans, 86% of them Navajo, totalling $372.6 million.

The Environmental Protection Agency counts 523 abandoned uranium mines on or near the Navajo reservation that spans Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, an area bigger than Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Vermont combined.

The Senate voted 69-31 in March to extend the RECA filing period for five more years, with 46 Democrats and 20 Republicans in favor, along with Sen. Krysten Sinema of Arizona and two other independents. Sen. Mark Kelly, D-Ariz., also supported the bill.

The bill has stalled in the House, with no explanation from Speaker Mike Johnson or Majority Leader Steve Scalise, both Republicans from Louisiana.

Their aides did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The Congressional Budget Office pegged the two year cost for the extension that expired in June at $86 million.

In March, a bipartisan group of 15 House members, including Democratic Reps. Ruben Gallego and Greg Stanton of Phoenix and Raúl Grijalva of Tucson, and Rep. Paul Gosar, R-Bullhead City, signed a letter to Johnson and other congressional leaders demanding an end to the logjam.

“It is unacceptable that extremists in Congress have let RECA expire and left hundreds of radiation-exposed Arizonans without the care and compensation they deserve,” said Gallego in a statement issued by his office.

The expiration has been a blow for Billiman.

In Sawmill, a Navajo Nation town of 1,032, most of her family and many others in the community are sick, she said. Those who lived in Sawmill during nuclear testing are eligible as downwinders for RECA compensation.

That included her father, Howard Billiman, who died in 2001. He served at Okinawa as one of the famous Code Talkers who used the unwritten Navajo language to protect U.S. military communications during World War II.

He was in and out of the hospital for about two years before he was finally diagnosed with Stage 4 stomach cancer, Billiman said. He died about six weeks later.

The family collected $50,000 under RECA since his death.

Maggie Billiman said she and her siblings have cancer and other ailments they blame on fallout. But she doesn’t have a diagnosis that qualifies under RECA and feels close to giving up.

Not only were Sawmill residents never warned about the nuclear testing, most never heard about RECA. Billiman has been handing out packets to help neighbors apply. Many have yet to do so, she said, making it vital for Congress to reopen the program

The EPA has funds to clean up 250 mines on Navajo land, spokesman Joshua Alexander said. Interim cleanup has been completed at 31 of the sites, and preparations are underway at 106.

Interim cleanup includes “excavating contaminated soil from residential areas, covering contaminated areas with clean soil, erecting fences, and posting signs to prevent exposure,” Alexander said by email.

A final cleanup of one site was completed in 2023.

EPA plans to start final cleanup this year at the Northeast Church Rock site, about 17 miles northeast of Gallup, New Mexico. That will involve moving 1.4 million tons of contaminated soil to the site of a shuttered United Nuclear Corporation Mill to consolidate the waste.

For some former uranium workers, the pending extension bill is a chance to finally be eligible under RECA.

That includes Linda Evers, who took a job at a uranium mill in northwest New Mexico, near Gallup, at age 18 when she graduated high school in 1982.

“When you’re in a little podunk town that has zero opportunities, it’s hard to not go get the money, and they knew that,” she said.

Congress limited RECA compensation to people who worked at the mines and mills from 1942 to 1971, after which the U.S. government was no longer the sole buyer of uranium ore.

“They just act like we’re the invisible dead people, and we’re starting to feel like it, too,” said Evers, 66, born and raised in Grants, New Mexico., a small town west of Albuquerque.

In 2007, she co-founded a group that advocates for people who worked in uranium mines after 1971 called the Post ’71 Uranium Workers Committee.

It started with 35 people. Now, she is the only one left as members died or became debilitated.

She worked at the mill for two years until 1978 when she had her first child. The stint overlapped with most of her pregnancy.

Her first child was born with a birth defect: a muscle wrapped around his stomach, making him throw up whatever he ate. Surgery addressed the problem and Evers returned to the mill.

Her second child was born without hips, requiring five major surgeries over six years.

Evers is certain her time at the mill caused her children’s maladies. Evers herself was diagnosed in 2000 with degenerative bone and joint disease that she attributes to early exposure to radiation. She has been living off disability payments since 2004.

The company never warned her about any dangers, she said.

“They … knew that they were gonna kill us,” she said.

Stanton, the Phoenix congressman, called RECA “a matter of justice,”

“What would be the cost if we were not to do this? What would be the cost of people saying, ‘My government has harmed myself or my loved one and hasn’t taken responsibility for that?’ ” he said in an interview.

Cullin Pattillo, an environmental engineer who lives in Kingman, 180 miles northwest of Phoenix, lost his father to liver cancer in 2022, and is furious with the House speaker for allowing the program to lapse.

“He’s playing politics while the government continues to get away with – and I’ll use a very blunt term here – they murdered my dad.” he said.

Eddie Dean Pattillo lived in Kingman his entire life, from 1939 to 2022, and blamed the multiple bouts of cancer he was diagnosed with starting in 1997 on exposure to radioactive fallout.

“He was a downwinder who fought over 50 years to get justice for the victims of Lower Mohave County from the U.S. government’s careless actions in the 1950s which exposed the entire area to radiation for over a decade,” reads the obituary.

Residents of Kingman were not made eligible under RECA, although the program covered other parts of Mohave County, where data showed fallout rates higher than in some counties covered entirely.

Objections about cost should not keep Congress from doing the right thing, said his son.

“This is something that has already been paid for. It was paid for by the lives of the people that have died,” he said.