WASHINGTON – For over 20 years, Arizona has banned noncitizen voting in local elections. Now as Rep. Ruben Gallego and Kari Lake tussle in the state’s U.S. Senate race, the issue is rising to the forefront.

Just last year, Gallego defended the District of Columbia’s policy allowing noncitizens to cast ballots in municipal elections.

But as the heat of an election year rises to a boil and hard-line Republicans stoke fears of illegal immigration and fraudulent elections, the issue has proved too toxic for Gallego as he seeks to broaden his appeal beyond his progressive base.

When the issue came up again in late May, Gallego sided with Republicans in an effort to overturn the D.C. law.

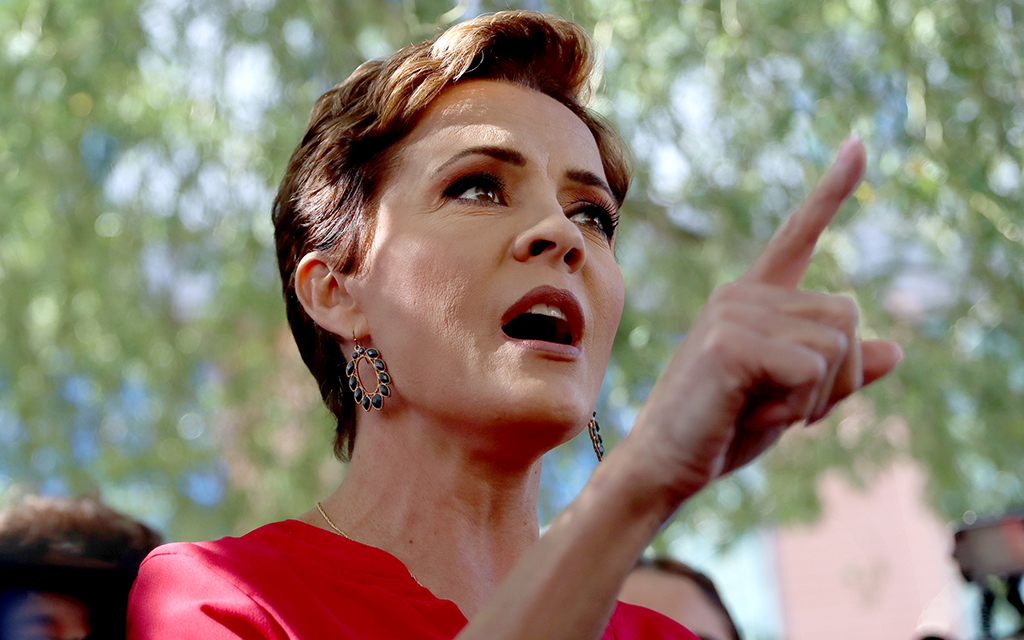

Lake, the GOP front-runner, slammed the Phoenix Democrat, who has served five terms in the U.S. House, as a flip-flopping opportunist.

Noncitizen voting has a long history in the United States. At least 15 cities allow it, all in predominantly Democratic states.

In the nation’s capital, where Congress has authority to overrule the local government, noncitizens have been allowed to vote in local elections for the last two years, though the June 4 primary is the first time they can actually do so.

According to the D.C. Board of Elections, 523 noncitizens were registered to vote in D.C., a number that may grow with Election Day registration on Tuesday.

D.C. already has one noncitizen elected official: Abel Amene, who arrived in 1999 from Ethiopia seeking asylum. He won a seat on a neighborhood advisory board before he was even able to cast a ballot, which Amene told the Washington Post he planned to do.

America has “quite an extensive history of immigrants being able to vote in elections, and not just local and state elections … but even federal elections,” said Ron Hayduk, a political scientist at San Francisco University who has written extensively about immigrant voting rights.

“The main criteria for who could vote historically did not revolve around citizenship. That came later,” he said by phone, noting that in the nation’s early days, white male property owners were most likely to enjoy the franchise. “What mattered most … was race, gender and class.”

It wasn’t until the U.S. began to break free of its colonial shackles and expand as an economic force in the 1920s that citizenship became the key eligibility criterion. Expansion of voting rights often required social pressure, whether from the Suffragettes at the turn of the 20th century or the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.

From 1969 to 2002, New York City let noncitizens participate in school board elections, as candidates and as voters, according to a report Hayduk co-authored. The City Council extended the right to lawful permanent residents and other noncitizens authorized to work in the United States in 2021. That change is on hold after a successful court challenge, which the city has appealed.

Wherever it’s been tried, the legality of noncitizen voting exists in somewhat of a gray area.

Hayduk said six states in addition to Arizona ban the practice in their constitutions: Alabama, Colorado, Florida, Ohio, Louisiana and North Dakota.

And not one state constitution explicitly allows it, according to research by Joshua A. Douglas, a law professor at the University of Kentucky. But he has identified 14 states with no clear impediments if a local jurisdiction wants to set rules that let noncitizens vote in local contests.

Takoma Park, Maryland, a liberal suburb of the nation’s capital, took advantage of the loophole after the 1990 census. Thanks to large concentrations of immigrants, election districts drawn with roughly equal populations had huge disparities in the number of eligible voters.

A year later the “Share the Vote” campaign was launched, aiming to balance the number of eligible voters in each district.

U.S. Rep. Jamie Raskin, a Harvard-trained constitutional law professor whose congressional district includes much of Takoma Park, wrote at the time that local officials “came to believe that the exclusion of noncitizens from suffrage offended two basic democratic principles: no taxation without representation, and the idea in the Declaration of Independence that government justly derives its powers from ‘the consent of the governed.’”

“It may be counter-intuitive, post-modern even, but it makes democratic sense,” argued Raskin, a Democrat.

Raskin defended the D.C. policy during the recent House debate, too, calling the GOP move to ban noncitizen voting – which Arizona’s Gallego and 51 other Democrats joined – “an attack on home rule.”

District officials weren’t trying to let Canadians or Mexicans influence national elections, Raskin pointed out, but “everybody presumably has the same basic interests in efficient garbage collection, excellent public schools and so on.”

Other Maryland cities followed in the decade after Takoma Park’s move. Currently 11 allow noncitizen voting in local elections, according to Hayduk’s Immigrant Voting Rights website. The biggest is Hyattsville, with a population of about 21,000.

Relatively few noncitizens typically avail themselves of the right. In 2017, just 72 of the 347 noncitizen voters registered in Takoma Park, which is home to about 17,500 people, cast ballots.

In 2016, 54% of San Francisco voters approved a charter amendment to allow parents and guardians of a child in the local school district to vote in school board elections, regardless of citizenship status.

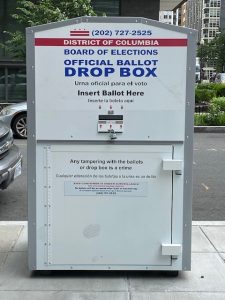

DC board of elections photo.jpg: A ballot drop box used by the D.C. Board of Elections. (Photo courtesy of D.C. Board of Elections)

A San Francisco County Superior Court ruled the amendment violated the state constitution in 2022. An appeals court reversed that in 2023. Oakland adopted a similar bill with 67% approval that took effect in 2023.

Like Takoma Park, few noncitizens have taken advantage of voting in San Francisco. In February 2022, 235 of 328 registered noncitizen voters cast ballots in a recall election.

In 2021, New York’s City Council extended the right to vote in municipal elections to lawful permanent residents and other noncitizens authorized to work in the United States. A state court deemed the bill unconstitutional, a ruling the city is appealing.

Over the past three years, three cities in Vermont – Burlington, Winooski and Montpelier – have all voted to allow legal residents of the United States to vote in local elections.

“It’s about basic democracy,” said Carter Neubieser, a local councilor in Burlington, by phone. “Sixty percent of people rent in this city. Much of the living conditions of those renters is determined by what city government does and how we do it.”

He cited zoning changes, user fees in parks and a variety of local programs. “All of these decisions are hyperlocal and affect everybody, regardless if you’re a citizen or not,” he said.

Noncitizens comprise about 5.5% of Burlington’s population of 45,000, according to the city. Only 62 voted in a March local election, out of 15,000 ballots cast, according to Vermont Public.

Despite low turnout in relatively few places that allow noncitizen voting, Republicans have used D.C’s legislation as a stick, depicting Democrats as soft on immigration and welcoming of election fraud.

Rep. Jeff Van Drew, R-N.J., said in a House debate that the effort shows the left is eager to “use the millions of illegal immigrants as political pawns to increase their power.” That glosses over the fact that the D.C. act pertains only to local elections, in a city where Democrats already hold an overwhelming edge.

Hayduk also noted the “minuscule” numbers of votes cast by undocumented immigrants, who could be subject to prosecution and potential deportation.

Gallego defended his support of D.C.’s noncitizen voting measure last year.

“I believe voting is a fundamental right reserved for the citizens of the United States, and I will oppose any effort to erode that right in Arizona and on the federal level,” he said in a statement. But, he added, local voting in D.C. has no impact on the rights of Arizonans or on national elections.

He called the bill an example of congressional overreach that left D.C. residents “at the mercy of a vindictive Republican House majority.”

When the issue came back to the House in May, however, Gallego sided with that “vindictive majority,” apparently calculating that inconsistency was less risky than appearing soft on immigration.

A recent CBS/YouGov poll found that almost 50% of Arizona voters deem the U.S.-Mexico border situation a “crisis.” Gallego – who leads by a commanding 13 percentage points in that poll, even as President Joe Biden trails Donald Trump in the state – also has used that description.

Kari Lake speaks at a Senate campaign event. (Photo courtesy of Kari Lake for Senate

Lake, his likely opponent for the seat being vacated by Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, slammed him for the turnaround.

“Flip-flopping on the issues now won’t trick Arizonans into thinking he’s a moderate after we’ve watched him vote for open-borders policies time and time again over his decade in Washington D.C.,” Lake said in a campaign statement.