FLAGSTAFF – Researchers at Northern Arizona University have launched a project to study persistent disparities in autism services for children from underserved communities.

The project was sparked by a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that showed, for the first time, the percentage of 8-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder was higher among Black, Hispanic and Asian or Pacific Islander children than white children. Before the 2023 Community Report on Autism, white children were identified with autism spectrum disorder at higher rates when compared to other racial or ethnic groups by the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network.

According to the ADDM, these findings might reflect improved identification among historically underserved populations and “it may be helpful to examine factors, such as social determinants of health.”

In response to this and additional evidence that “Latino, Black or American Indian and Alaska Native” children face inequities in accessing critical autism care, Olivia Lindly, an assistant professor in the Department of Health Sciences at Northern Arizona University, is leading a research project to study “persistent racial and ethnic disparities in access to autism services for U.S. children enrolled in Medicaid.”

Lindly and her team seek to clarify past and ongoing racial and ethnic disparities in access to autism services, with an ultimate goal of creating “multi-level strategies, programs and policies” to improve access. The NAU study was formally announced on Jan. 8, and is funded by a $2.9 million grant from the National Institutes of Health.

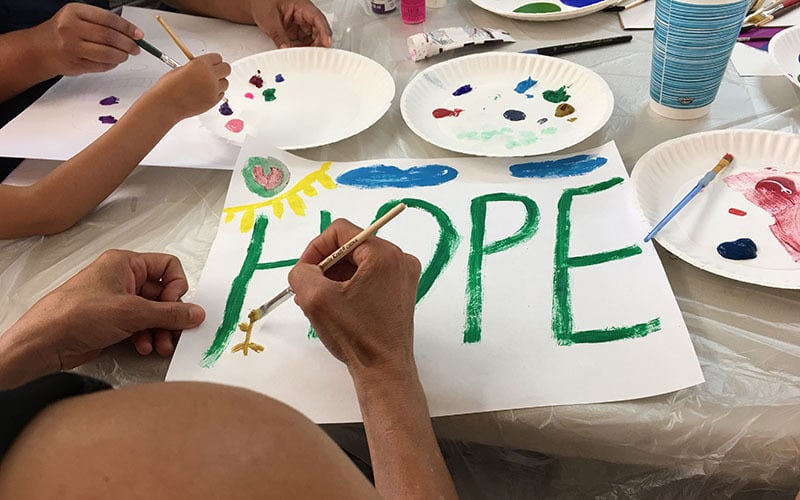

Since coming to NAU, Lindly has been adapting the Parents Taking Action program, an education and training program for parents of autistic children, to include the Indigenous community.

“About 30 percent of the population in Coconino County identifies as Indigenous, and the majority of that 30 percent are Diné or Navajo,” Lindly said. “We decided to work with Diné parents of autistic children and other service providers in this region in adapting the program. It’s helped facilitate several more community-based initiatives coordinating care for autistic kids, including those who are in the Navajo Nation.”

Diagnoses struggles in AZ

According to Lindly, the research project originated from questions about autism diagnoses within Arizona.

“Why do we have differences at a state level in the prevalence of autism?” Lindly asked. “It signals there are disparities in how many kids are being diagnosed. Some of the things we’ve found is that Arizona has a fairly restrictive policy around who is able to diagnose autism so that kids can qualify for services through the Division of Developmental Disabilities.”

Lindly said these restrictions by the state led to both a lack of services provided through the division, as well as fewer providers who can legally diagnose autism.

“There is a limited quantity of people who can provide therapy services like behavioral therapy, occupational therapy,” Lindly said. “So a lot of times, kids end up getting therapeutic services for the first time in the school system, in kindergarten or first grade. Then, they have to undergo this whole process of attaining an educational autism diagnosis.”

Coming from working in cities like Boston and Portland, Oregon, Lindly had to adapt to the rural Arizona landscape when she started her research.

“I think for me, it has been very surprising the lack of resources and services supporting families in this region,” Lindly said. “I’ve been really inspired by people’s interests and dedication to trying to improve the system and organize more at a community level.”

Racial and ethnic barriers to access

While struggles with diagnoses play a role in accessibility, Lindly also pointed to the need for recognizing racial and ethnic barriers to care. The research team’s preliminary interviews with parents of autistic children revealed a lack of cultural responsiveness.

“We’ve heard from some parents that they may have a doctor or health provider doing a diagnostic autism assessment for their child who is not Native,” Lindly said. “Those providers don’t always understand some of the beliefs and traditional practices that Native families may have related to autism.”

The Autism Society of Greater Phoenix advocates for the Arizona autism community and is one of many organizations providing educational resources. To address a language barrier that inhibits some from accessing care, the organization recently translated all of its training courses into Spanish.

Olivia Fryer, executive director of the Autism Society of Greater Phoenix. (Photo courtesy of Olivia Fryer)

“It came about through a grant from the Arizona Coyotes last year, and the Arizona Coyotes Foundation,” said Olivia Fryer, the society’s executive director. “With that grant, we were able to translate all our ‘101’ trainings, including Autism 101, Transition 101, as well as Safety 101. We now have them available online, readily available for anybody to access.”

As the parent of a child with autism, Fryer has a personal understanding of the resources available to autistic families in Arizona.

“My son was first diagnosed with autism when he was 3 years old, and prior to that, I really didn’t have a lot of knowledge about autism,” Fryer said. “Once he got his diagnosis, I was just one of those parents who threw myself into the community and absorbed any and all information that I possibly could.”

In Fryer’s experience, provider numbers have increased in recent years but rural communities still struggle with finding adequate care.

“With the growth and development that Arizona has seen, there’s a multitude of providers to choose from, but we definitely still see a need for more,” Fryer said. “Especially in outskirt areas. We get a lot of phone calls from families who live in the city of Maricopa or in some of the reservations, and there’s just not adequate access to resources there.”

Project progress and upcoming work

According to Lindly, the research team wrapped up the pilot phase of its program and presented the first round of findings to a community advisory group on March 29. The team also recently received additional funding from Aetna Health to further its work.

“We plan to hopefully sustain and expand the Parents Taking Action Program for Diné families in person at Tuba City Regional Health Care,” Lindly said. “We are hoping that we can involve a larger number of families and train some additional parents to serve as community health workers to directly deliver the program to other families.”

In addition, Lindly and her team are looking to partner with hospitals to see if they can embed parental education and training into existing programming.