PHOENIX – Non-English speakers can face big communication challenges in medical settings: being unable to convey personal information, understand medical jargon and follow treatment instructions. These challenges can result in misunderstandings, or worse, in misdiagnoses. Phoenix hospitals work at preventing problems like this by providing interpretation and translation services in many different languages.

About 2 million Arizonans speak a language other than English, according to U.S. Census Bureau data, although it is not clear how many would be considered non-English speakers. Over 1.3 million speak Spanish; more than 130,000 speak another Indo-European language; 150,000 speak an Asian or Pacific Island language; and 160,000 speak other languages.

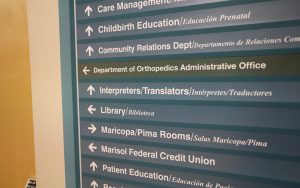

Phoenix hospitals, including the Mayo Clinic, Valleywise Health, Abrazo Health and Banner Health, have established services for interpretation – for speech – and translation – for written communication – that can cover dozens of different languages. When a hospital’s language department is unable to directly provide interpretation and translation services, third-party providers – vendors and contractors – will step in.

Two medical professionals shared their experiences on how language services change health care accessibility for many underserved people who could fall through the cracks.

Banner Health Estrella – Elsa Perez

Elsa Perez, a Spanish-language medical interpreter at Banner Estrella Medical Center, says that interpretation services are a big help for patients. “They’re getting all the information, all their medication, all their diagnostics in their own language so they can understand,” Perez said. (Photo by Kevinjonah Paguio/Cronkite News)

Elsa Perez is a Spanish-language medical interpreter at Banner Health Estrella. She knows the challenges a language barrier can present. She interpreted for her parents during doctor visits, speaking to them in Spanish and trying to answer questions health providers asked in English.

“It could be something as simple as, ‘Have you had a bowel movement?’ I don’t know what that was as a 10-, 11-year-old kid,” Perez said. Doctors would reword their questions, but it was still difficult to convey the message to her parents.

After a career working for the state, Perez looked into working in the medical field and found a position for a Spanish-language medical interpreter. “I thought, ‘Hey, I already know the language. I kind of already know what I’m doing,’” she said. She took classes and realized that she did not know Spanish well enough to do the job, saying that she spoke more “street Spanish” than “school Spanish.” She overcame that challenge.

As a Spanish-language medical interpreter, her work helps patients who don’t know English to understand the information doctors give. “It’s a great deal of help,” she said, “because they’re getting all the information, all their medication, all their diagnostics in their own language so they can understand.”

She still faces challenges. For example, she said people speak many different versions of Spanish: Mexican Spanish, Dominican Spanish, Puerto Rican Spanish, to name just a few. This can cause misunderstandings between medical staff and the patient.

“One little word can mean (something) totally different in Puerto Rico or Colombia,” she said.

She recalls a case when a diabetic patient’s sugar levels weren’t going down and doctors couldn’t understand why. He was doing everything by the book – he had a good diet, took his insulin and his medication. After two or three appointments, Perez realized that the patient, who was from Puerto Rico, was drinking about a gallon of orange juice a day. This wasn’t caught because he referred to orange juice as “green tea.”

Perez says interpreters and translators have to be ready for any situation.

Valleywise Health – Martha Martinez

Martha Martinez is the manager of language services at Valleywise Health. “I want every human being to have information and health care in their language,” she said. (Photo by Kevinjonah Paguio/Cronkite News)

“I remember doctors – I guess because of my name, my last name and my skin color – they would say, ‘Oh, I think you speak Spanish. Can you please help me with interpretations?’” she said. “Without being trained, without knowing, really, medical terminology, I would do my best to help the doctors.”

A misdiagnosis by a bilingual medical professional, however, prompted Martinez to become an interpreter. The medical professional said that Martinez had a sexually transmitted disease, whereas she actually had a urinary tract infection. What made the experience worse was that this professional told her “You shouldn’t be playing around with men.” Martinez’s husband was present for the whole interaction.

“I couldn’t say anything,” she said. She explained that when she came to the United States and people didn’t speak her language, Spanish, she just took whatever they would say. “You just don’t fight. You just don’t ask.”

That event inspired Martinez to go to school, learn medical terminology and many years later, she became manager of language services at Valleywise Health. She wants everyone to get the right medical information. She also wants to advance cultural sensitivity because it plays such an important part in medical care.

She recalls a case when a woman came in with various issues. The patient had gone to a yerberia – an herb remedy store – and it turned out that the herbs she took were interacting with her medication. “The doctor was asking all the questions,” Martinez said, “but he never took in consideration our culture, where sometimes we take herbs.”

The interpretation services at Valleywise Health will be Martinez’s legacy.

“Back 30 years ago, there were no programs (to train interpreters),” she said. “Now, it’s a career.”

She knows her work has an impact. “Young generations will say, ‘Wow, you know, that’s good for you,’” she said. “I guess my generation would say, ‘We’re so proud of you, you being a Latina and doing this for the whole community. It’s wonderful.’”

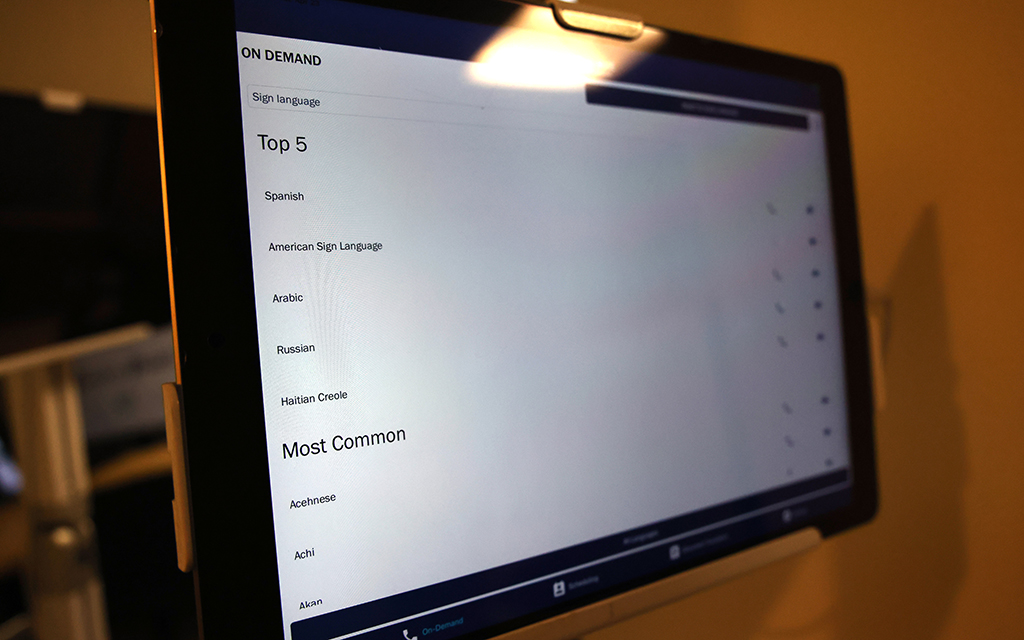

Phoenix hospitals provide other services to break the language barrier in health care. In addition to interpreters and translators, both Valleywise Health and Banner Health offer over-the-phone and video services. Banner utilizes VRIs (video remote interpreters) while Valleywise uses iLISA (Language Interpretation Services Anywhere), its form of VRI.

Nevertheless, Perez and Martinez believe that interacting with a human being is the best form of communication.