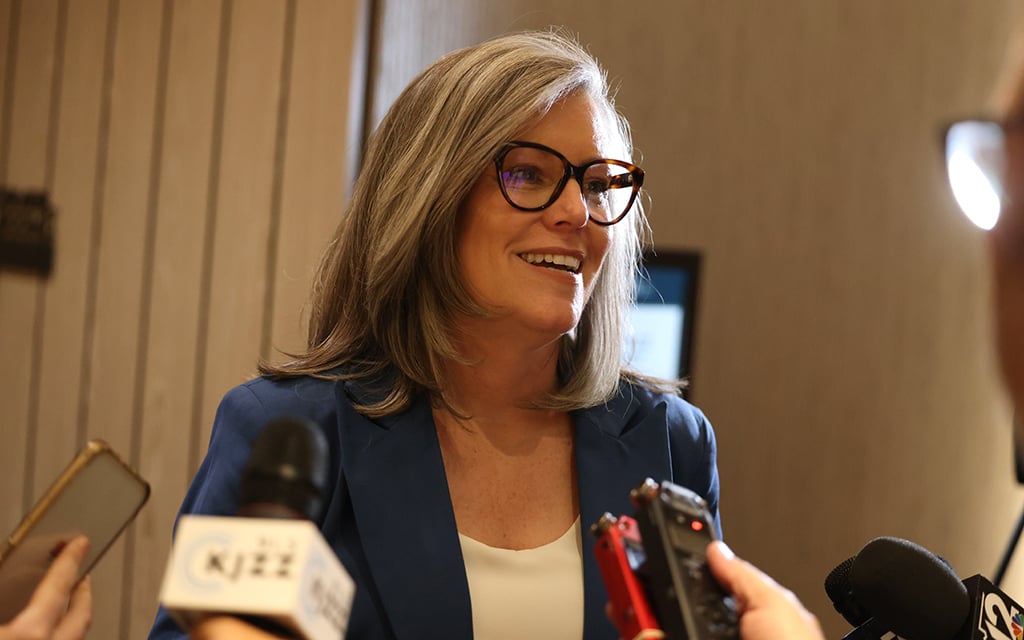

The governor’s office is partnering with RIP Medical Debt, a nonprofit geared toward clearing personal medical debt. (File photo by Marnie Jordan/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX — On March 4, the governor’s office announced that Arizona is partnering with RIP Medical Debt, a national nonprofit organization dedicated to clearing Americans’ medical debt, to cancel the debt of up to 1 million Arizonans.

In making the announcement, Gov. Katie Hobbs said the program will help working Arizonans who have incurred debt from cancer treatments, life-saving surgery and accidents “through no fault of their own.”

According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Arizonans had over $2.4 billion in medical debt in 2020. The RIP Medical Debt program is expected to forgive up to $2 billion of that debt, according to the governor’s office.

An analysis of government data by the KFF-Peterson Health System Tracker shows that 8.2% of Arizonans, or about 460,000 people, have medical debt in a given year. The data is aggregated from the Survey of Income and Program Participation from the U.S. Census Bureau from 2019 through 2021.

And the nonprofit Urban Institute reports that 12% of all medical debt incurred by Arizonans went into the collection process; that jumps to 16% for communities of color. The median medical debt for communities of color in Arizona is $774, compared to $686 for white Arizonans, the institute said.

Hobbs will use up to $30 million from the federal American Rescue Plan Act that will let RIP Medical Debt “purchase and forgive billions in medical debt held by medical providers.” American Rescue Plan funds must be spent by Dec. 31, 2026, when the act expires, according to the Urban Institute.

The program is available to Arizona residents who earn up to four times the current federal poverty level or have debt that’s 5% or more of their estimated household income, according to the governor’s office.

People do not apply for this program. The nonprofit analyzes hospital and other medical provider debt portfolios and identifies individual accounts that qualify. The people who can benefit from the debt cancellation are then notified.

Providers must sign non-disclosure and business associate agreements to protect patient health information that will be submitted to RIP Medical Debt for analysis. Hospitals will decide whether to sell or donate patient debt to RIP Medical Debt at a discounted rate.

Daniel Lempert, vice president of communications and marketing at RIP Medical Debt, a nonprofit geared toward clearing personal medical debt. (Courtesy of RIP Medical Debt)

“If a government has $1 of ARPA funds, that translates to $100 on average of medical debt erased,” said Daniel Lempert, vice president of communications and marketing at RIP Medical Debt.

Misty Rowe is an Arizonan whose medical debt was erased by RIP Medical Debt before the current deal was struck. Her debt was incurred due to complications delivering her second child, who didn’t survive, she said.

Rowe said she had what’s known as HELLP syndrome, a group of symptoms that can occur with preeclampsia and threaten the health of both the mother and the baby. HELLP is an acronym for hemolysis (the breakdown of red blood cells), elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count.

The mortality rate for women with HELLP is up to 24%, and the perinatal mortality rate is up to 37%, according to a study published in the Journal of Prenatal Medicine

Rowe said her symptoms started with an upper abdominal pain that she mistook for gas; as it got worse, she went by ambulance from one hospital to another until finally a third hospital was able to treat her, she said.

“Sweetheart, you’re very sick. I’m going to do my best to make sure you don’t leave here a vegetable, but you’ve got to work with me,” she remembers one of the nurses telling her.

When the ordeal was over, she found herself with more than $7,000 of debt from hospital and ambulance charges. She said it hurt her credit and made it difficult to rent or buy a house.

“Medical debt is something unsolicited. I didn’t wake up in the morning and be like, ‘I’m going to go rack up $7,000 in medical debt today,’” she said.

Health insurance doesn’t protect Arizonans from going into medical debt, according to the American Journal of Public Health. Health insurance rarely provides complete protection from financial loss caused by illness or injury.

Misty Rowe owed about $7,000 in medical debt until it was cleared by RIP Medical Debt. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

The percentage of people who had trouble paying their medical bills or who accrued medical debt – or both – rose from 34% in 2005 to 41% in 2007, according to the American Journal of Public Health. Medical bills can be more difficult to pay off than other kinds of debt because illness or injury limits the person’s ability to work.

Rowe said debt collectors were relentless in their pursuit of her, and weren’t willing to compromise on how to pay it off.

“They don’t want to cut you a break. There were times where I’d be like, ‘What if I paid you this much and we’ll just wash the debt?’ and they’re like, ‘Nope, nope, we want the full amount,’” she said.

Outside of contracts with state or local governments, RIP Medical Debt works by acquiring debt from health care providers and debt collection agencies, sometimes at steep discounts, and then uses private donations to cancel the debt. Lempert said Rowe’s debt was paid from a church fundraiser at Redemption Church Gateway, which is now known as Ironwood Church in Mesa.

Some hospitals refuse to sell their medical debt because of predatory debt collection practices; however, Lempert said, those hospitals sometimes will sell debt to RIP Medical Debt once they understand how the nonprofit operates.

“It’s getting over that hurdle of just trying to explain that we’re not the same as a for-profit collection agency,” Lempert said.

Local governments in Toledo, Ohio, and Cook County, Illinois, have already implemented similar programs, Lempert said.

He emphasizes that although the nonprofit is there to help people, it’s no substitute for proper health care reform.

“You really can’t point at providers or insurers, right? There are bad actors out there, but for the most part the whole system needs an overhaul,” Lempert said.