PHOENIX – Minority communities without access to adequate prenatal care often suffer high maternal and infant morbidity and mortality rates. In Arizona, approximately 1 in 6 infants in 2022 was born to a woman who didn’t get adequate prenatal care.

Mobile maternity care clinics are making a difference by bringing prenatal care into communities where it’s needed. These maternity care clinics, on wheels, connect expectant mothers to accessible and timely medical services.

A new mobile care unit, called the Mom and Baby Mobile Health Center, made its debut at the Healthy Mama Festival on March 9 in Phoenix, giving tours to health care professionals and community members. Hosted by March of Dimes and Equality Health Foundation, the festival brought together providers and mobile care units from across the Valley in order to showcase accessible and affordable resources.

Lynne Robinson, a volunteer at the festival and representative from CVS Health, said that events like the Healthy Mama Festival bring resources directly into the community.

Lynne Robinson, a Healthy Mama Festival volunteer and CVS representative, shares how she got involved with March of Dimes. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

“Accessible health care is important because these resources specifically work with babies,” Robinson said. “These are individual, little humans who have no control over anything. If we can make sure that a mother has what she needs, then we are going to start a generation of healthier people.”

Robinson’s own involvement with prenatal care accessibility in Arizona began in 2003, following the loss of her son.

“I am a mother,” Robinson said. “I lost a child years ago, and that was how I came to be familiar with March of Dimes. When I lost my son, March of Dimes was the organization that stepped up and gave me the moral and communal support I needed.”

Umaja Isaiah, a mother of two daughters who is expecting her third child in April, attended the festival to learn more about available resources in Phoenix.

“As a mom and expecting mother, there is always room to learn more,” Isaiah said. “Not all folks can afford health care. It is really important to make sure everyone has equal access, because everyone deserves it.”

Isaiah pointed out that maternity care mobile clinics can provide prenatal care to people who might not realize they need it. Robinson said it’s “important for moms to show up.”

“Because once we realize we have a child and life in our body, we are excited, but none of us really know what the next steps are,” Robinson said. “When there are organizations and entities that have that information, for the sake of our own health as well as that of the baby, it’s important to find that information. We don’t know what we don’t know.”

Care disparities in Arizona

Shadie Tofigh, director of maternal and infant health with the March of Dimes. (Photo courtesy of March of Dimes)

In 2021, Arizona was ranked 26th in the nation for its infant mortality rate, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with 5.47 infant deaths per 1,000 live births that year. Within the state, there is one primary maternity care desert in Greenlee County and three low-access-to-care sites in La Paz, Cochise and Graham Counties, according to March of Dimes.

Disparities in access to care are reflected in the state mortality rates. The Black community and American Indian/Alaskan Native populations had the highest infant mortality rate when compared to other groups in 2023, according to a report by March of Dimes.

“The infant mortality rate among babies born to Black birthing people is 2.1 times the state rate,” said Shadie Tofigh, director of maternal and infant health with March of Dimes. “Our American Indian and Alaskan Native population comes in second. It’s also the same with preterm birth.”

The Association for Women’s Health Care advises pregnant people to have their first prenatal visit as soon as possible and schedule regular care visits every four weeks through week 28, and more frequently after that. Women in underserved communities, however, often can’t follow that schedule. Inadequate prenatal care is defined as either care starting in the fifth month or later, or care that includes less than 50% of the recommended number of visits.

Tofigh explained how lack of prenatal care access can lead to pregnancy complications and health issues down the line.

“This includes high rates of preterm birth, maternal morbidity and mortality, and potentially infant morbidity and mortality,” Tofigh said.

Joe Russo, senior director of strategic partnerships and innovation at ASU Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

Joe Russo, senior director of strategic partnerships and innovation for the Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation at Arizona State University, identified some of the major barriers to accessing prenatal care in Arizona.

“Can you get to a clinic, a provider or a hospital?” Russo asked. “We live in a state that does not have great public transportation, and even just our infrastructure is complicated. Anything to deal with having babies and raising babies is going to be complicated. Not everyone knows or even believes that prenatal care is important.”

According to Tofigh, another barrier is the number of women in Arizona who lack health insurance. Data collected by March of Dimes indicated that 13.2% of women ages 15 to 44 were uninsured in 2019.

“The state of Arizona has passed Medicaid expansion for prenatal and postpartum patients,” Tofigh said. “Hopefully in the next couple of years, there will be a dual reimbursement policy, which will play an integral role in facilitating pregnant women accessing prenatal services.”

Maternity care clinics on wheels

Mobile care clinics work with communities to connect expectant mothers to hospitals for additional care and births.

Gail Brown, women’s health nurse practitioner on the MOMobile. (Photo courtesy of Dignity Health)

The St. Joseph’s Maternity Outreach Mobile Unit, also known as the MOMobile, has been providing maternity services across the Valley since it first launched with March of Dimes in 1995. Equipped with exam rooms, an ultrasound machine and a laboratory, the MOMobile can provide care that was once only available in clinics.

Gail Brown, a women’s health nurse practitioner on the MOMobile, talked about the geographical factors they considered when creating the traveling clinic.

“The more centrally located you are, you can find more services, especially in a large city like Phoenix,” Brown said. “Those that live further out in suburb areas have fewer choices for affordable care, if they are low income and uninsured.”

The St. Joseph’s MOMobile follows a weekly, rotating schedule, creating a widespread network of accessibility. It travels to Glendale on Mondays, Mesa on Tuesdays, Goodyear on Wednesdays and Phoenix on Thursdays, and is open to the public from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. on those days.

While the MOMobile provides critical prenatal care, it also helps connect expectant mothers to health care providers and hospitals for follow-up care and births..

“It takes a larger community,” Brown said. “You can’t just go out and provide the care in those areas. You have to be able to also provide the follow-up care, the place of delivery. But you still need to get out there and at least start.”

The recently launched Mom and Baby Mobile Health Center was developed in partnership with March of Dimes, the ASU Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation and Wesley Community and Health Centers.

To expand this quality of care to all expectant mothers and families, the Mom and Baby Mobile Health Center addressed affordability head-on. Because Wesley Community and Health Centers is a federally qualified health center, according to Russo, they receive certain support funds to cover costs.

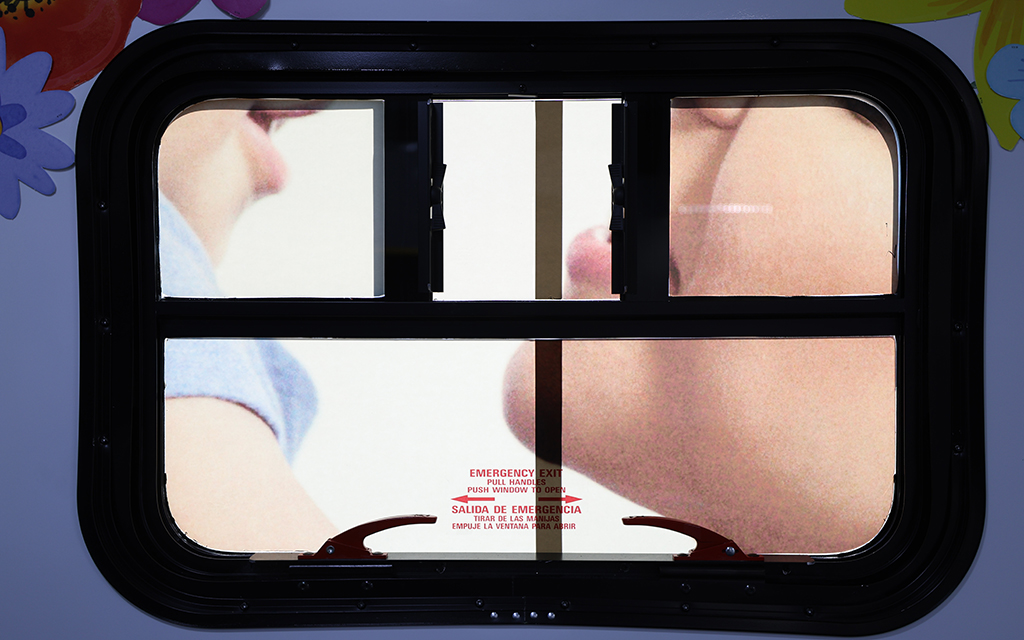

The Mom and Baby Mobile Health Center bus. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

“They’re able to offer care using what we call a sliding fee scale,” Russo said. “When people come in, if they do not have insurance, the cost of their care is able to be adjusted based on what income they do have.”

What distinguishes this clinic from other mobile clinics in Arizona is its increased focus on education. Russo said the clinic will simultaneously create a teaching environment for ASU nursing students through hands-on experiences.

“Every minute we are in the community, we are also going to have nursing and nurse practitioner students on board, learning in this community care setting,” Russo said. “The students who are working on this mobile unit can develop their capstone projects around certain needs we are seeing in patients and can also be a part of the solution.”

Laura Maurer, a doctor of nursing practice for Wesley, will serve as the nurse practitioner provider on the new mobile center. She believes that mobile units like theirs have the capability to make connections beyond mothers and infants.

“We know that women are usually what I call the gatekeepers of health for their family,” Maurer said. “So if we can get the women in the clinic, a lot of times they are going to drag their husband or father in. Then, we can treat the whole family.”