PHOENIX – When Christopher Carrillo discovered a lump behind his ear in 2011, it never occurred to him that the cause could be from HIV.

“Testing wasn’t something that I did,” Carrillo said. “It wasn’t part of my routine.”

After Carrillo researched lymph nodes online and saw a mention of HIV, he decided to see a doctor. The results changed his life forever.

Today, Carrillo is a case manager at the Southwest Center for HIV/AIDS in Phoenix, a health-care facility serving primarily “persons of color, LGBTQIA2S+ and Queer individuals, and those affected by HIV.” He sees a recent wave of new HIV cases in Arizona changing the lives of the Hispanic population around him.

In January, Arizona reported a 20% increase in new HIV cases in 2022. According to the HIV surveillance report, 405 of the 975 new HIV cases in the state were Hispanic patients, more than any other ethnic group, representing a 10% increase from 2021.

Valleywise Community Health Center–McDowell, a Phoenix clinic that offers HIV and AIDS care to underserved communities, said it has seen a significant increase in patients over the past decade and is currently seeing a spike in numbers of new HIV cases.

“When I started in this clinic 13 years ago, we had 2,500 to 3,000 patients,” said Dr. Ann Khalsa, the clinic medical director at VCHC. “Now we’re over 4,000 patients.”

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) is the virus that causes AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), a disease that has killed millions of people around the world. In 1987, the Food and Drug Administration approved a drug regimen that finally reined in the spread of the disease. There is no cure for AIDs, but anti-retroviral drugs have made it possible for many people to live indefinitely with HIV.

Khalsa, who has been involved with HIV care since the late 1980s, said the HIV epidemic changed when the United Nations launched its Fast-Track cities program in 2014 – an initiative dedicated to lowering HIV rates in urban areas.

“(Fast-Track cities) focused on getting 90% of people (in major cities) diagnosed, 90% of them linked to care and also getting that 90% virally suppressed,” Khalsa said. “Phoenix has been a member of the Fast-Track city initiative since 2016.”

Khalsa said the recent statewide increase could be due, at least in part, to more frequent testing, following a deficit of testing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Khalsa said she saw funds for increased testing were “finally starting to be used” in 2022.

“In 2020, we saw decreased testing rates and diagnoses because people weren’t circulating due to quarantine,” Khalsa said. “Now, we’re seeing that reversal as things start to trickle up.”

Khalsa said that when patients receive rapid treatment, they are more likely to stick with a long-term program. The state reported that 79% of patients diagnosed with HIV in 2022 received treatment within 30 days.

“Part (of Fast-Track cities) is getting people who are newly diagnosed immediately into care so that they don’t feel scared, but rather feel embraced,” Khalsa said. “That helps their health as well as the community spread.”

Dr. Ann Khalsa, clinical medical director at the Valleywise Community Health Center-McDowell, a Phoenix clinic offering HIV testing and treatment. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

Facts and figures

Khalsa said that in 2023, 53% of HIV patients at Valleywise were MSM – men who have sex with men – while 47% were bisexual or heterosexual, and the largest ethnicity among Valleywise patients was Hispanic, 30 to 39 years old.

Carrillo said the increase of HIV in the Hispanic community most likely has to do with the culture.

“It goes back to being gay,” Carrillo said. “In the Hispanic community especially, people don’t talk about it, so there’s a fear of getting tested and not wanting to find out (if they have HIV.)”

Khalsa said 87% of Valleywise’s patients are young men who don’t see doctors for regular health care, and are often uninsured or underemployed.

“They come to us because we’re a ‘safety-net hospital,’” Khalsa said. “We have the Ryan White contract, so we can treat patients who don’t have current active medical insurance.”

Valleywise says the McDowell clinic is the only location in Maricopa County where patients can receive support to pay for their HIV treatment through the Ryan White Program, a federally funded service providing HIV/AIDS care to low-income patients. The program website states it has helped more than 550,000 people nationwide.

While Khalsa said only a fifth or less of Valleywise’s patients use the Ryan White Program on a continuous basis, the number of patients who have used the program overall is much higher.

“Particularly since the end of the COVID pandemic, swathes of people were dropped off of AHCCCS and ended up uninsured for a while,” Khalsa said. “We’ve had a large uptick in utilization of the Ryan White funding recently.”

According to Khalsa, the program has been effective in keeping those with HIV out of the hospital.

“One week in the hospital is $50,000 to $100,000 and one year of HIV meds are $20,000 to $30,000″ without insurance, Khalsa said. “The government has known it’s far cheaper to keep people healthy and on meds than it is to let people progress and end up in the hospital.”

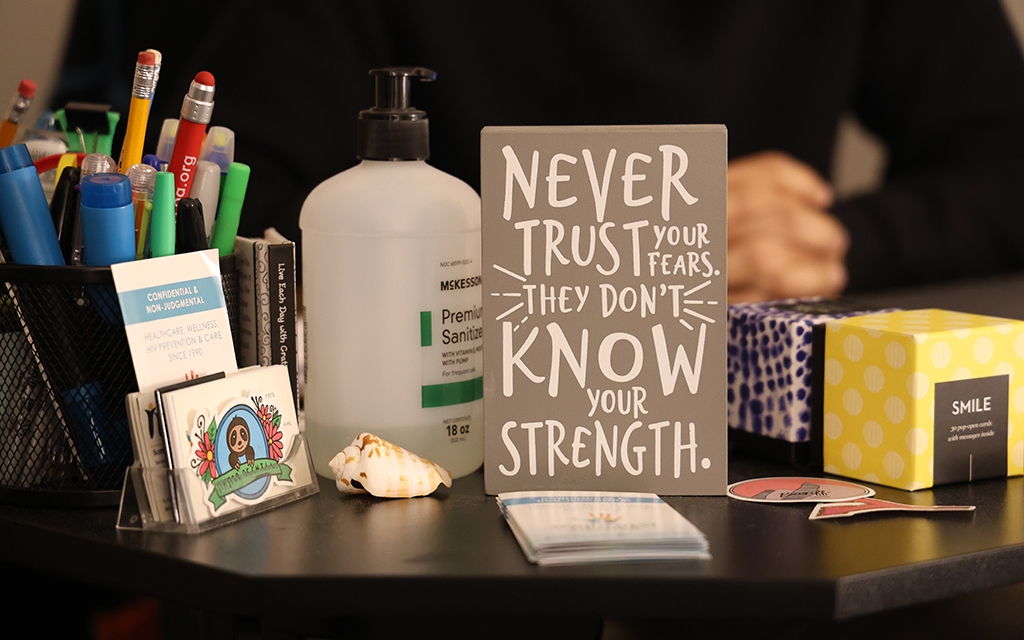

An encouraging slogan on the desk of Christopher Carrillo, case manager at the Southwest Center for HIV/AIDS in Phoenix. He spoke about being tested and treated for HIV and the affirmations that have helped him. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

The importance of advocacy

Carrillo remembers what it was like receiving his positive HIV test results.

“It was devastating,” Carrillo said. “I grew up with the stigma surrounding HIV, so I thought it was a death sentence. I was just given a pamphlet and sent on my way. I felt all alone.”

Carrillo helps new HIV patients navigate their diagnoses by hosting a support group and connecting patients with treatment resources.

“I didn’t want the next person (with HIV) to go without services or to feel alone,” Carrillo said. “That’s why I do what I do.”

Following his diagnosis, Carrillo turned to drug abuse and avoided HIV treatment for four years, isolating himself from his family and friends in the process.

“I turned to the drugs to cope, and when I eventually told my family, I told them I probably have a few years to live,” Carrillo said. “Eventually, I had a clear mind and I told myself, ‘I’ve got to do something about my health. I’m still here.’”

Although Carrillo was told by health care professionals that he was “undetectable” for HIV – meaning the virus is so low that it cannot be transmitted to a sexual partner – he currently takes medication to control the virus and keep it from multiplying.

“I’m on a once-a-day pill,” Carrillo said. “It’s very important to take it at the same time and that I take it every day so I don’t build any resistance to the medication. The virus is pretty smart.”

Having grown up in a small mining town in Arizona, Carrilo said HIV wasn’t something people openly discussed.

“I thought it was another STI (sexually transmitted infection),” Carrillo said. “It wasn’t something I learned in school and I had only heard about it a few times in adult conversation. …That’s why it’s so important to educate the community and normalize getting tested.”

Despite the ongoing stigma, Carrillo is hopeful that those who are younger will diminish the anxiety around routine testing.

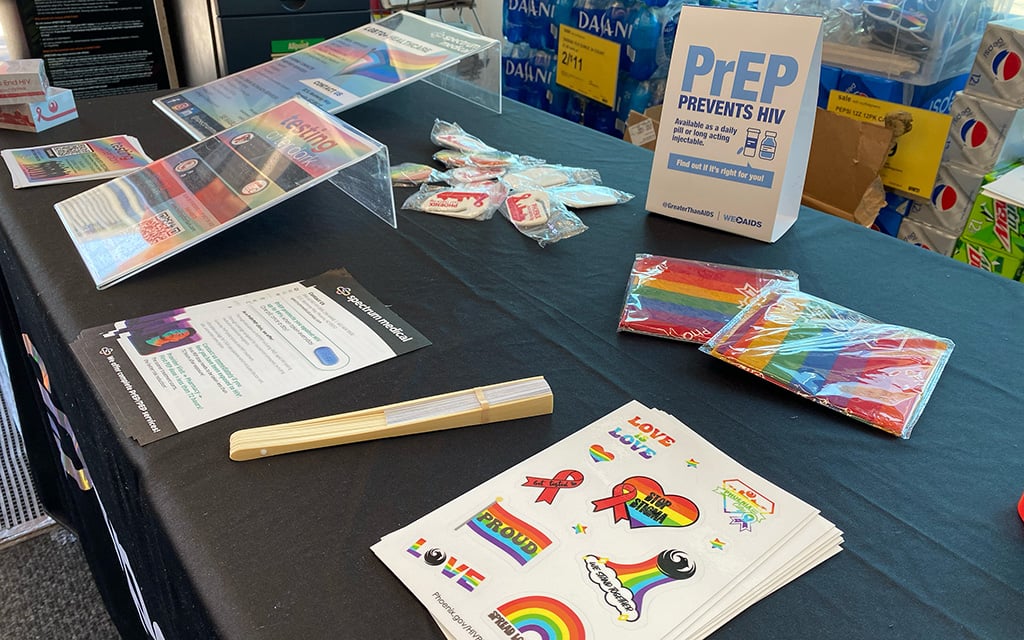

“I do see a lot of the younger generation less fearful,” Carrillo said. “They’re comfortable with getting tested and starting on PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis is medicine to prevent getting HIV). … It’s the stigma that’s preventing the person from accepting their diagnosis because they’re worried about how they’ll be viewed. I do my best to ensure people get to live a full life, no matter what happens.”