PHOENIX – Ronny Morales never finished his journalism degree at Arizona State University. After attending the school for four years, the Cronkite Noticias student was just one internship credit short of graduating.

Morales said it was not his lack of enthusiasm or experience in the field that prevented him from graduating, it was his fentanyl addiction.

“The first newscast I did (for Cronkite Noticias), I was not necessarily in the grips of addiction quite yet, but I was definitely falling into it,” Morales said. “And then towards the end, I was trying to get off and I think you could see it.”

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid drug that produces feelings of euphoria, relaxation and pain relief. According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, it is approximately 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin as a pain reliever.

In 2023, fentanyl was involved in nearly 75% of verified non-fatal opioid overdose events in Arizona, according to the Arizona Department of Health Services.

On Feb. 6, Morales and his mother, Martha Ayala, told his story at a forum on fentanyl addiction conducted in Spanish and hosted by the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office and the Equality Health Foundation.

According to the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office, more than 250 people attended the forum, the highest attendance number for any of MCAO’s forums, and 240 Narcan kits were distributed.

Like many who become addicted to opioids, Morales’ problem started with a prescription. As a 19-year-old college student in 2012, Morales was in a serious car accident and was prescribed Percocet, a branded opioid drug, for three months.

“Within those three months, my body became physically – and definitely psychologically – dependent on those opiates,” Morales said.

The doctors stopped prescribing the pain medication and Morales experienced intense withdrawals. He bought Percocet from someone with an active prescription in an attempt to end the symptoms, unaware of the long-term consequences of this action.

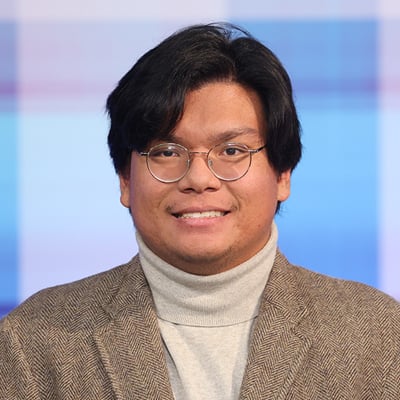

Ronny Morales, on Jan. 31, opens up about his past use of fentanyl. “I tried stopping almost every year,” he said. (Photo by Kevinjonah Paguio/Cronkite News)

“Every physical pain that I was experiencing from the withdrawal and all my anxiety just went away within 30 minutes. I felt absolutely incredible and I thought I found the secret to life,” Morales said of the temporary relief continued use of drugs brought him.

Morales purchased more drugs like Vicodin, Adderall and cocaine as his addiction worsened. Despite their diminishing effect, he continued to use them regularly in order to keep up his energetic and vibrant personality.

“Within maybe close to a year is when I started not necessarily feeling the high anymore,” Morales said. “It became my coffee. In order for me to wake up and be alert and coherent, I needed to be high.”

Along with these drugs, Morales primarily used fentanyl. For over seven years, Morales rationalized his daily drug usage and denied he had an addiction. When he was fired from his job at a radio station for driving a company car with a revoked license, he realized he could not continue living under the influence.

“I tried stopping almost every year, countless times. I went to a few rehabs, I went to a few detoxes. Ultimately, that didn’t work,” Morales said.

Throughout the course of his addiction, Morales lived with his mother, who was unaware of her son’s drug use. Morales said he had always been a good kid and Ayala never suspected he would be using drugs.

“She knew that I was going through something but she just couldn’t fathom the thought that that’s what was going on,” Morales said. “I’ve always been dramatic, but the last thing she would think is that I’m on drugs.”

During one of Morales’s detoxes, his mother confronted him about his odd behavior. He told her he was having fentanyl withdrawals. She knew nothing about the drug but she wanted to help.

“She’s from a little town in Mexico so that was just incredibly overwhelming for her,” Morales said. “She doesn’t know where I’m going, and she doesn’t know what I’m getting.”

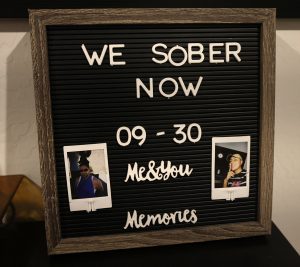

A plaque commemorates the start date of Ronny Morales’s sobriety, now in its fourth year. (Photo by Kevinjonah Paguio/Cronkite News)

After that moment, Morales said, Ayala sought other ways to support and help him end his addiction. Together, they confronted cultural barriers that kept many in their Hispanic community from addressing their substance use.

“The culture is so stubborn when it comes to accepting things like mental health or addiction,” Morales said. “I know that there’s people that are struggling and not coming forward because of things like their culture or their language barrier, or they might not even have the documents to be here. So they have no choice but to just stay in that addiction.”

Morales said that the key to his recovery was taking everything one day at a time. Eventually, he began attending support groups where he found he was often one of the few Hispanic people in the room.

“I don’t think it’s because I’m one of the few Hispanics struggling with addiction or alcoholism. I just think it’s a lot to do with the culture, the language barrier or documentation,” Morales said.

In 2023, Hispanic people accounted for 30% of the 1,865 opioid overdose deaths in Arizona, according to the Arizona Department of Health Services.

Linda Garcia is the assistant bureau chief for the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office and was one of the other panelists at the Feb. 6 forum. She said the forum intended to break down the language barrier that prevents many Hispanic people from reaching out for help.

“We have had a presence of the community in English community forums, but it’s obviously better to have it in Spanish so that there is a better understanding,” Garcia said. “The public feels a lot more comfortable asking questions in their native tongue.”

Morales is now four years sober and the host of the podcast, Wesobernow. After gaining a following on TikTok for content about his journey, Morales began his podcast to inspire others to reach their sobriety goals. Now, he said, his podcast audience helps him stay sober.

“In a good way, just from sharing my story, ultimately, that really drove me to stay sober,” Morales said. “This is the longest I’ve ever been sober.”

Morales said the first step in his recovery was recognizing the problem, the second was asking for help. He contributes much of his sobriety to his support system, including his husband of just over a year, Nathan Truitt. The key person throughout, he said, was his mother, who took the initiative to learn and struggle alongside him.

“She still fought with me,” Morales said. “That’s how I know what real love is. Just fighting for someone or something without even necessarily knowing why. It’s because you just want the best for them.”