PHOENIX — When David Karr finally sought help for his debilitating depression, he didn’t anticipate the long road ahead.

“I got tired of looking at the ground,” Karr said. “When you’re depressed, that’s all you do.”

Karr, who has a chronic mental illness, said he was treated by state mental health providers in the past but failed to receive long-term help. He explained how his journey toward mental stability came about through a found object art piece he named “Lost Horizons.”

“I call this ‘the dancer,’” Karr said, pointing to a wooden stick on the canvas. “She’s a beautiful dancer, but she can’t always dance because of her SMI (severe mental illness) conditions. It gets in the way of her talent.”

Karr’s art can be found throughout the walls of Community 43, a nonprofit, licensed outpatient clinic providing psychosocial rehabilitation services for adults with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or major depression, among others.

Karr said he received an SMI (Serious Mental Illness) designation and spent time in the state mental health system. According to the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, an SMI is “a chronic and long term mental health condition that impacts a person’s ability to perform day-to-day activities or interactions.”

Designation can be requested through a number of sources – including an insurance provider or tribal regional behavioral health authority – and enables access to certain services that could improve a person’s quality of life and ability to live independently.

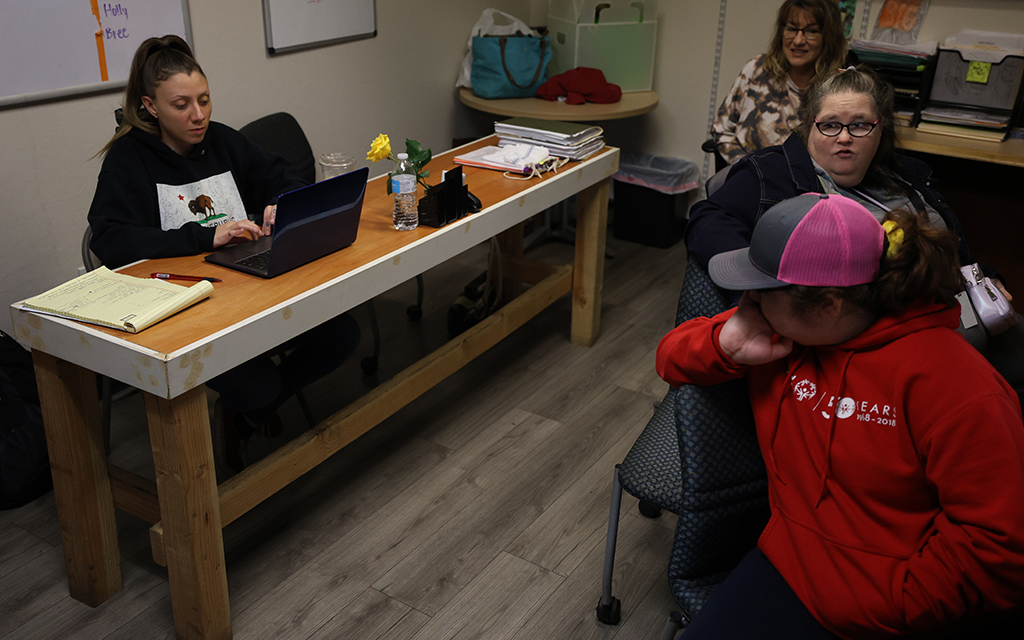

What sets Community 43 apart from traditional outpatient clinics for people with SMIs is its “clubhouse” model of psychosocial rehabilitation services, which provides opportunities for individuals with chronic mental illnesses to develop their social and cognitive skills. The objective of Community 43 is to foster independence and “assimilate people with serious mental illness into the larger community.”

Clubhouse staff Bre, behind the desk, meets with members of Community 43 on Jan. 23. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

Common treatments for severe mental illnesses

Psychosocial rehabilitation is an important part of treating the whole person, according to Mike Franczak, director of population health services for Copa Health, an Arizona nonprofit that advocates for people with disabilities.

Franczak said the most common form of treatment for individuals with SMIs follows a “biopsychosocial model” – patients are treated based on how their biological, psychological and social health are affecting their mental well-being.

“What we try to do today is create ‘whole person care,’” Franczak said. “We need to deal with the physical side of health, the behavioral side of health and social determinants of health.”

Like the biopsychosocial model, Franczak said psychosocial rehabilitation also addresses these issues simultaneously.

“If you only focus on the biological aspects, you aren’t going to get the same effect unless you factor in those psychological and social things,” Franczak said. “Psychosocial rehabilitation is applying that to a person at the same time. It’s just a matter of putting it all together.”

Franczak said that while there is value in psychosocial rehabilitation, the most crucial component is a patient’s desire to voluntarily undergo treatment.

“You can present all of those things to some people who are just going to say ‘I don’t need that,’” Franczak said. “But if the person is a willing participant and if they desire to receive it, it can work very well.”

Community 43 supports people with mental illness through socialization, education and skill training, and offers recreational opportunities to help members regain independence.

Karr, a Community 43 founding member, and CEO Kara Cline collaborated to bring the facility to life based on a Clubhouse International model. They said the Phoenix facility is the first of its kind in Arizona.

Clubhouse International is a nonprofit organization based in New York with facilities in 32 countries around the world. Its stated mission is to “end social and economic isolation” for people with mental illness through rehabilitative services.

“When you walk through (Community 43), you shouldn’t be able to tell who’s a member and who is staff,” Cline said. “Members help run the clubhouse. They even help decide who gets hired, help with interviews and answer the phone.”

Currently, 650 active members utilize the clubhouse on a regular basis. Once a member’s application is approved, they can use the clubhouse as long as they wish for free.

“There’s no end date because your condition ebbs and flows throughout your life,” Cline said. “But the end goal is self-sufficiency.”

Karr said the open-endedness of the clubhouse gave him a sense of permanence that no other facility had.

“I left for five months,” Karr said. “When I came back, it was like I had never been gone. You’re not able to do that with any other program.”

To aid members’ transitions to independence, the Clubhouse International model follows a “work-ordered day,” where volunteers can carry out tasks like helping in the kitchen, maintaining the garden or running the welcome center.

A staff member known as “Goose” works in the kitchen at the Community 43 clubhouse on Jan. 23. (Photo by Jack Orleans/Cronkite News)

“It’s that need to be needed,” Cline said. “It’s OK if the job isn’t done perfectly, but it’s what develops a sense of self again.”

Karr spoke about his experience in what he refers to as a “never-ending cycle” of mental illness that continues when a person does not receive love or respect – two things the clubhouse is built upon.

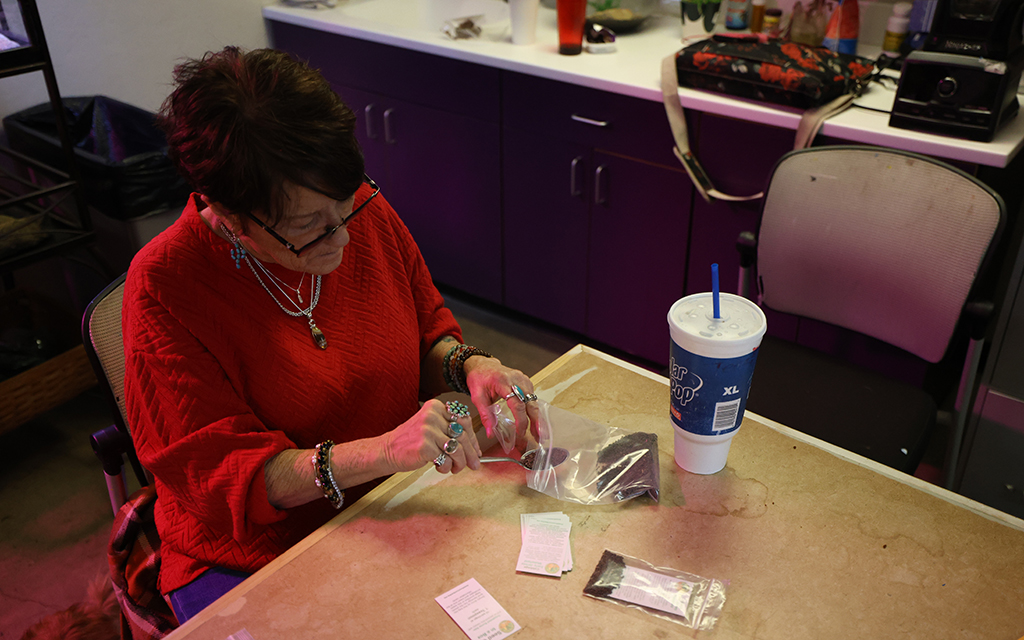

Although Community 43 does not provide members with hospital resources, Cline said an on-site primary care physician is able to fill members’ prescriptions and conduct check-ups as needed.

“We also have a psychiatrist, two nurse practitioners and an R.N.,” Cline said. “You may have something physical going on that’s affecting your mental health. Why wouldn’t we integrate the whole person?”

The medical clinic is separate from the treatment facility but connected by a single hallway in order to encourage members to tend to their medical needs as well as mental health needs.

“Traditionally, this is a population that doesn’t take very good care of themselves,” Cline said. “We’ve caught things like early onset diabetes and major dental issues, including infections … all of that affects your mental health.”

Cline said that although Community 43 gets most of its funding from donations and in-house fundraisers, Medicaid funds a small portion of their program.

“By Arizona law, some Medicaid money has to go to the services we provide,” Cline said. “We’re setting up Arizona in the Clubhouse community. … There’s houses all over, but they’re often really small, all donor-funded and not comprehensive.”

While Cline said Community 43 is still developing – it opened in 2021 – Karr believes the clubhouse model is powerful enough to turn a person’s life around.

“It’s the best-kept secret,” Karr said. “I’ve seen some amazing turnarounds in my time here. We look at the good in people, not what’s wrong with them.”