The Arizona desert’s unforgiving summer temperatures pose a significant challenge to athletes and coaches, leading them to adapt and implement strategies to avoid health issues. (Photo by Patrick T. Fallon/AFP via Getty Images)

Arizona athletes and coaches navigate the scorching summer challenges, from record-breaking heat to air quality concerns.

PHOENIX – Few things go together as well as peanut butter, chocolate milk … and the brutal Arizona heat.

As the Valley recovers from what has been its hottest summer ever measured – Phoenix broke its own record in July with a 31-day streak of temperatures above 110 degrees – experts continue to search for the best ways to keep athletes safe as the mercury rises.

From treats such as the peanut butter and chocolate milk, which have side benefits that help athletes stave off the heat, to modernized gadgets like heat stress monitors, athletic trainers have evolving options to help combat the relentless summer days in the desert.

“In order to play football in Arizona, you can’t be a soft kid, and you can’t be a soft coach,” said Chandler football coach Rick Garretson.

Phoenix is known for its scorching summers, with temperatures sometimes reaching 115 degrees by the afternoon, just as some practices begin. And it appears that it is only getting worse.

From July through September, 42 days featured historical heat warnings, the National Weather Service reported.

September in Phoenix reached 105 degrees and the average temperature this year in Phoenix has been 94 degrees, according to Weather Spark. That’s the average temperature of the entire 24 hours, not the average high.

At the pinnacle of the heat wave in July, some Arizona high school football teams opted to train in cooler temperatures in northern Arizona or travel entirely out of the state. Some schools can’t afford that luxury, and others don’t want it.

Perennial powerhouse Chandler High opted to stay close to home.

“A hundred and two degrees for my kids is nothing,” Garretson said. “You know, when you have the heat we’ve had here, 116-117 degrees for several days, obviously we take the precautionary steps of how we go about our business (getting) under the shade and (drinking) water. Our players adapt to it and are in very good condition.”

Athletes who train properly in the heat could have an advantage by getting their bodies acclimated.

Judd Erickson, a former Division I quarterback at the University of San Diego who now plays for the Cologne Centurions in the American Football International, has first-hand experience playing in hot and humid temperatures recently in Europe.

“I played a game in Paris, and it got up to 90 outside,” he said. “It might have been a little hotter on the turf.

“We had a couple of guys who actually couldn’t go because it was too hot. We had one guy who had a heat stroke. He ended up sitting out most of the second half.”

Heat illnesses vary, but all start with a form of heat cramping. What differentiates them is an altered level of consciousness.

According to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, a heat stroke is the most serious heat-related illness and can put a strain on the brain, kidneys, liver and lungs.

“You’d go into a heat syncope due to the heat,” said Saguaro athletic trainer Nickie Edwards, describing a fainting episode or dizziness. “Then you get to heat exhaustion. If that goes untreated, it leads to heatstroke, which is when that core temperature rises above 104 degrees.

“Your brain is literally cooking, and we’re in a life-threatening medical emergency.”

But even when athletes aren’t suffering a heat illness, their performance can suffer when temperatures are high. That’s where proper nutrition can help.

The best foods to consume during halftime of football games, according to Erickson, include lots of fruits, including bananas, watermelons and oranges. Quick-digesting sugars like fruit snacks and honey help replenish nutrients.

“We encourage them to have high-carbohydrate snacks throughout the day,” Edwards said. “We want them to consume salty carbohydrates. So we like cheese, crackers, pretzels, bagels, and peanut butter.

“The salt is actually going to be important as you’re sweating, we want to get those electrolytes back in as we deplete electrolytes in our sweat.”

Athletes and coaches are arming themselves with modern gadgets like heat stress monitors and turning to nutrition, including chocolate milk, to combat the sweltering weather conditions. (Getty Images stock image)

Chocolate milk has even been shown to have a beneficial effect on bodies for recovery purposes.

The carbohydrate content of chocolate milk is double that of plain milk, water or most sports drinks and it contains protein, making it ideal for tired muscles. Dehydration is prevented by its high water content, which replaces fluids lost through sweating.

“You’re getting it in about a two-to-one carbohydrate-to-protein ratio,” Edwards said. “Which is your optimum ratio for being able to turn those proteins into muscle tissue for protein synthesis.”

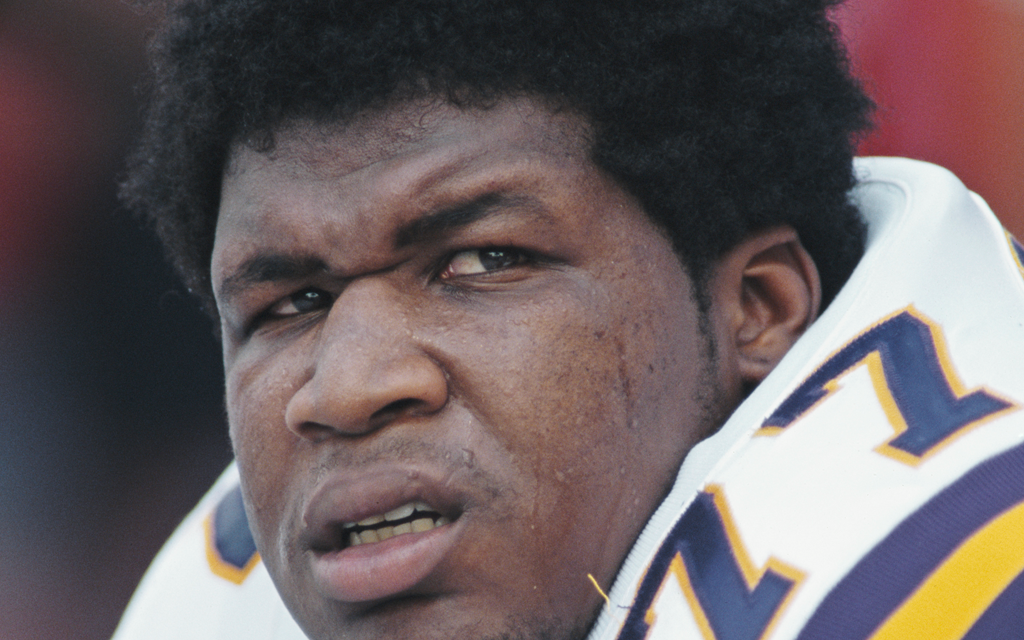

A tragic heat-related death in the NFL helped magnify the need for more awareness of heat illnesses in sports. In August 2001, Korey Stringer, an offensive lineman with the Minnesota Vikings, collapsed during training camp and died from exertional heat stroke.

His unexpected death at 27 was not caused by a heart attack or a genetic disease. Sports medicine largely overlooked the avoidable and manageable condition of exertional heatstroke at the time, which caused Stringer to pass out.

The Korey Stringer Institute was created “to provide research, education, advocacy and consultation to maximize performance,” as well as to enhance the safety of all athletes with the goal of preventing sudden death.

“When the Korey Stringer Institute came out, it was a tsunami to all of us in the healthcare industry,” said Dr. David Carfagno of Scottsdale Sports Medicine Institute.

The Wet Bulb Globe Temperature is one of the measures now being used to help athletes avoid heat stress thanks to the Korey Stringer Institute.

“It’s a temperature reading that combines the relative humidity, wind speeds, ambient air temperature and your field surface temp,” Edwards said. “Most of us athletic trainers in the state use a device called a Kestrel, which is the heat stress meter. It’s a device that we use that sits on a tripod. They use them at (Arizona State University) and in professional sports. They’re used nationwide.”

The heat stress meter is placed near the field and takes constant weather readings throughout practice. It sends alerts via Bluetooth to the trainer’s smart phone.

The green category of wet bulb globe temperatures means there are no restrictions for practice.

The yellow category means a minimum of three breaks are required. The orange category requires football players to be in helmets, shoulder pads and shells only and requires four separate rest breaks each hour.

If the meter reaches the red category Edwards said, “We want to make sure our football players, in particular, are not wearing any equipment because the added equipment increases their core temperature and decreases their ability to reduce that quartet.”

If the Wet Bulb Globe reaches the black zone, no outdoor activities are allowed at all.

“It is really, really important that athletic directors, coaches and school districts give their athletic trainers the authority to modify practice based on the scientific data that we collect,” Edwards said.

Korey Stringer’s legacy serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of heat safety in sports and the dangers of extreme heat. (Photo by Scott Halleran/Getty Images)

There is a reason football has received the most attention regarding the severity and number of external heat illnesses.

“Part of it is that football is seasonal,” Carfagno said. “And for us out here in most places, that’s the peak of summer. So a lot of the teams are out there doing preseason during the hottest time of the year.”

According to the Korey Stringer Institute, “When examining deaths that have occurred from exertional heat stroke during American football, most of the deaths (~65%) have occurred during the month of August in the eastern quadrant of the U.S. In addition, over half of the reported deaths occurred during morning practices when humidity levels were high.”

And excessive heat can spawn other problems, such as poor air quality.

When extreme heat is accompanied by poor air quality, the concerns skyrocket. As a result of extreme heat and stagnant air during a heat wave, air pollution and ozone pollution increase.

“I always recommend all my athletes to look at the AQI (Air Quality Index), and focus on the air quality pollutants,” Carfagno said. “Try to exercise indoors during the extreme weather times in June, July, and August.”

Playing in dry heat means sweat depletes the body of moisture – often without the athlete realizing he or she is becoming dehydrated because the sweat quickly evaporates in Arizona’s dry heat. Even athletes who have trained over the summer may not be fully adapted to extreme temperatures under the conditions associated with a sporting season.

“Prevention is the absolute key to the best way to treat any of these heat illnesses, making sure that we’re keeping our athletes safe and putting a good product on the field,” Edwards said.

Edwards added that the No. 1 way to do that, in her opinion, is to have a certified athletic trainer on hand.

“And No. 2,” she said, “listen to them.”