WASHINGTON – When federal student loan payments resume this fall, they are expected to pull as much $71 billion in otherwise disposable income out of the economy every year, $5.3 billion of which will come from Arizona.

The economic pain could be very real for the 43 million borrowers – about 880,000 in Arizona – who will have to start paying back their student loans after a pause of more than three years that began as a pandemic-relief measure.

“We hear from borrowers, some even in Arizona, who are telling us that when payments restart, they’re not going to be able to afford food, they’re not going to be able to afford rent, they’re not going to be able to afford health care,” said Cody Hounanian, executive director of the Student Debt Crisis Center.

While the amount those repayments will pull from the economy appears daunting, a Moody’s Analytics report said it will only account for about 0.4% of the nation’s disposable income, what Moody’s economist Bernard Yaros calls a “modest headwind” to the overall economy.

“It’s a drag, but it’s a very modest one at that and it’s really not enough to derail the economy,” Yaros said, noting that the payments are projected to reduce personal consumption expenditures by 0.2% next year.

Yaros said slowing inflation, interest rates that are likely at their peak and a stubbornly resilient job market all hold more weight in the long-term health of the U.S. economy than the dollars that will be lost to the loan payments over the next year.

“None of this is to minimize the micro impacts that this will have on certain demographics or certain households,” Yaros said. “For certain groups of people, this is going to be big, they will have to pull back on their spending in order to start making these student loan payments.”

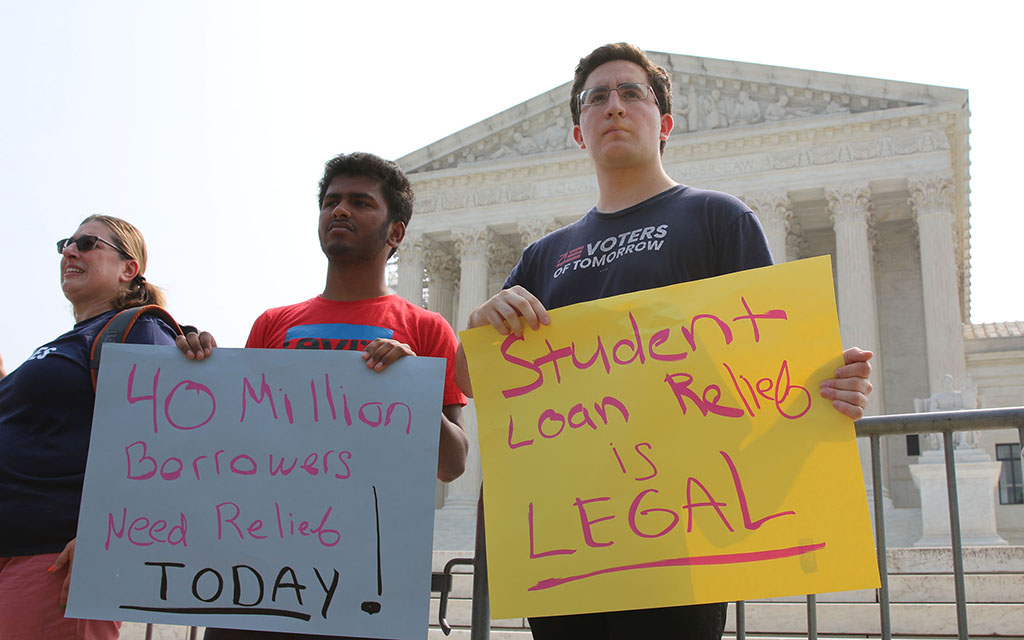

Repayments are scheduled to restart Oct. 1, after a whirlwind summer in which Congress voted to block the Biden administration from further extensions of the pandemic-era moratorium, and the Supreme Court overturned a separate White House plan that would have forgiven up to $20,000 of some borrowers’ debts.

Biden, who campaigned on a promise of broad debt relief for student borrowers, has since responded with alternative plans that his administration hopes will stand up to congressional and Supreme Court demands.

Those include a repayment “on-ramp” – which protects borrowers’ credit scores by not reporting missed payments for a year – and an expansion of a current plan that caps monthly payments for some borrower to 10% of income and forgives loan balances after 20 years of regular repayment. The expanded plan would halve those limits, to 5% and 10 years.

Before the president announced his latest plans in June, the Education Data Initiative estimated that $5.3 billion will be siphoned from Arizona’s economy by debt repayments. That’s about 1.5% of the state’s $350 billion gross domestic product, said Lee McPheters, an economics professor at Arizona State University’s W.P. Carey School of Business.

McPheters said the repayment “is one of those things where the impact on those individuals affected by the policy is large but the overall impact on the economy is relatively small.”

He estimated the average individual monthly student loan payment in Arizona will be around $500, or about $6,000 per year. With a median Arizona family income of $75,000, that means borrowers will put roughly 8% toward repayments.

“Younger consumers with smaller annual income will have to make some hard decisions about their spending, but overall the economy will continue along the normal business cycle,” McPheters said.

The Moody’s analysis found that regions of the country that have the highest student loan balances also had a below-average median age.

Yaros said the amount of debt “does not seem as onerous in Arizona compared to other states,” particularly East Coast states. Moody’s said Philadelphia had the highest debt, at $5,859 per capita, and the Atlanta metro area was second-highest, at $5,830.

By comparison, the Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale area was highest in Arizona, at $3,749 student debt per capita, followed by Flagstaff, at $3,274. Yuma had the lowest debt per capita in Arizona, at $1,675.

Rawley Heimer, an economics professor at the Carey School, pointed to the multiple universities in Arizona that have “relatively low tuition” as one reason for the relatively low debt of state residents.

“The typical Arizonan who goes to those schools is almost certainly left with significantly less financial obligation than somebody who, for example, might go to an expensive private school out of state,” Heimer said.

But he and McPheters agreed that, while relatively low, the payments are not necessarily good news for young borrowers who have low incomes and high debt balances.

“Younger people are trying to save up for large purchases, so it could have effects on the housing market where people who previously were trying to save up money for a down payment are instead going to have to pay back their debt obligations,” Heimer said.

The Supreme Court’s rejection of Biden’s debt-relief plan is “particularly impactful for younger individuals, who have not benefited from a lot of the government policies that have been in place for many years” that have allowed older generations to build wealth, he said, pointing to mortgage income tax deductions.

Facilitating such intergenerational wealth transfers could benefit the economy in the long-run, Heimer said.

“Any time the government can give a gift to people who are younger generations of 20 to 40 or so, I think it’s a net benefit for the country’s economic future as a whole,” he said.

Even in a state like Arizona, and even with the benefits of Biden’s latest debt-relief plans, Hounanian said there is still a longer-term threat to the economy from the resumption of student debt repayment. He said the plans, while well-intentioned, will only delay an inevitable series of student-debt defaults, which he worries will hold “dire consequences” for vulnerable borrowers.

Hounanian pointed to a June Consumer Financial Protection Bureau survey that found roughly one student debt holder in five has risk factors that suggest they will struggle when payments resume. That includes an increase of 24% in other monthly debt payments since the start of the pandemic.

“We, along with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Federal Reserve are really concerned about a wave of student loan defaults, either 12 months from now, two years from now, once you know the domino effect of all of this really starts to tap in,” Hounanian said.

The study pointed to the progressive rise in interest rates over the course of the three-year moratorium, which translated to higher monthly payments across debt products.

Hounanian said those increases, along with factors including an increased cost of rent and housing and a lack of clear information on student loan repayment programs have “multiplied” the financial obstacles borrowers faced even before the pandemic.

“Many will have to choose default over, you know, the safety and health of their family,” Hounanian said. “When a borrower is faced with making a student loan payment, or keeping a roof over their head, they go with a roof over their head.