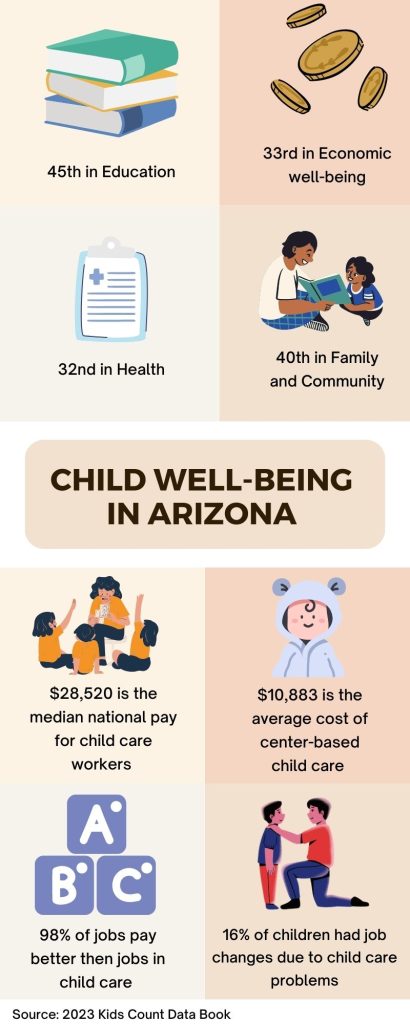

PHOENIX – An annual report that measures the well-being of children showed slight improvement for Arizona kids, but the Grand Canyon state remained among the lowest-ranked states.

On a national level, fewer parents were economically secure, educational achievement was hit hard because of the aftereffects of the pandemic and more children died young than ever before, according to the 2023 Kids Count Data Book. One of the biggest areas of concern in Arizona and the country was the lack of access to affordable child care.

Published Wednesday by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the data book ranked Arizona 39th overall. Rankings were compiled from national and state child welfare statistics across four factors – family and community, economics, education and health. Last year, Arizona came in 44th.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation is a private national philanthropic organization dedicated to bettering the lives of the nation’s youth who are at risk of poor educational, health and socioeconomic outcomes.

“Child care is an essential service,” said Children’s Action Alliance interim President and CEO Kelley Murphy. (Photo courtesy of Children’s Action Alliance)

States’ rankings were grouped in four categories: best, better, worse and worst. Arizona ranked worse in two categories (economics and family and community) and worst in two categories (education and health), putting Arizona near the bottom of the overall rankings.

“We fall into the worst category, again,” said Kelley Murphy, Children’s Action Alliance interim president and CEO. “The top headline for me is that any movement we’ve had has been minimal. After you stay in that space for so long, it becomes a choice. You’re making choices that put you in that position.”

The state ranked 32nd in health, 33rd in economic well-being, 40th in family and community and 45th in education.

Issues with child care seemed to be the overarching topic of concern in this year’s edition of the data book.

Murphy said shortcomings in Arizona’s child care system leave women, people of color and those on the lower end of the socioeconomic scale in jeopardy.

“The child care system is really in disarray and in crisis,” Murphy said. “The overall impact is that people who live in poverty are forced to stay in poverty because they have to quit jobs because it’s more expensive to put their child in child care.”

Children’s Action Alliance is the Annie E. Casey Foundation Kids Count partner in Arizona. The nonprofit strives to improve the welfare of children and families through partnerships and policy recommendations.

This year’s data book reported the national annual cost of center-based child care for toddlers at $10,883, or 31% of a single mother’s income and 11% of a married couple’s income. Additionally, 16% of children’s families across the country suffered job changes due to child care problems.

“If they can find a job that pays them adequately then they are not eligible for services, but they don’t make enough money to actually pay the cost of child care on its own,” Murphy said. “So it creates a cycle where we keep people in a situation where they can’t get ahead.”

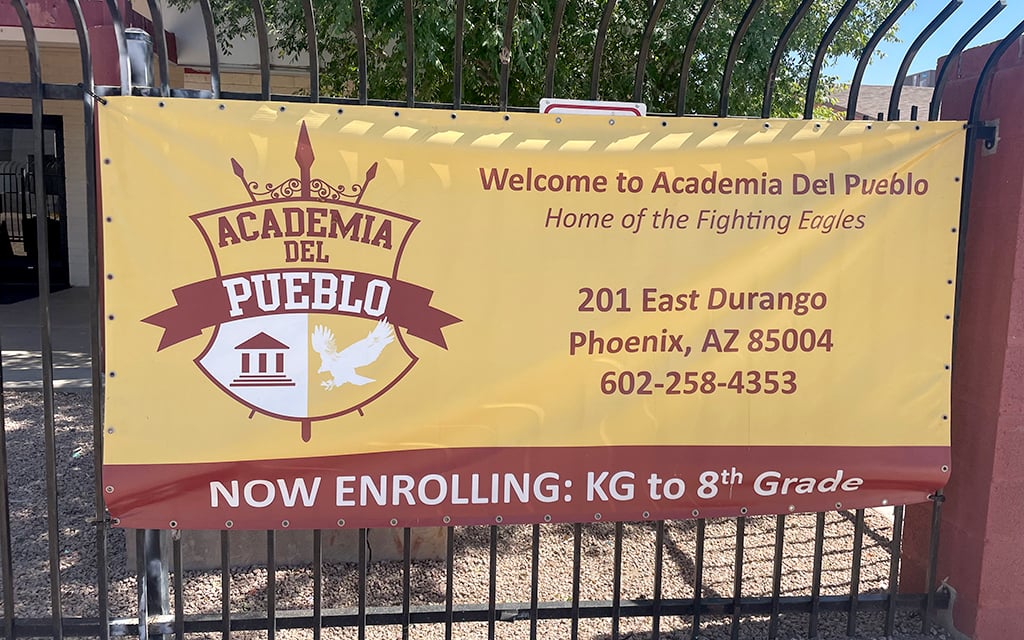

Friendly House’s Academia Del Pueblo, a kindergarten through eighth grade charter school near downtown Phoenix, tries to make child care work for families, an employee said. Academia Del Pueblo is a Title 1 school, meaning a high percentage of enrolled children come from lower-income families. The school provides free lunch, tuition and after-school care for all of its students.

The school does charge for its Early Childhood Development Center, said Jose Hernandez, assistant principal of operations. He said the pre-school offers among the lowest rates for child care in the state.

Jose Hernandez, assistant principal of operations at Academic Del Pueblo, said the Early Childhood Development Center rates are priced so that low-income families can afford to send their preschool children there. Photo taken on Tuesday June 13, 2023. (Photo by Sophia Biazus/Cronkite News)

“We’re charging $24.99 a day because we know the community that we’re serving,” he said. “We want our kids here. We don’t want them anywhere else.”

The estimated cost for a week of child care at Academia Del Pueblo’s Early Childhood Development Center is $124.95. The average weekly cost of child care for a 4 year old in Arizona is about $164.37 a week, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

Murphy said she expects more child care providers to close because extra funding during the pandemic is scheduled to run out in August.

During COVID-19, the state created a plan that increased access to child care through funding from the Arizona Department of Economic Security. State agencies, the Governor’s Office, community partners and stakeholders know this issue is a cause for concern, Murphy said, adding that she believes a lack of access to child care will continue to worsen in the next year.

“There’s probably going to be some additional shifting,” she said. “We may lose some providers for whom it’s no longer feasible for them to stay in business, but we’re working diligently to try and prevent that.”

Hernandez said that prior to COVID-19, enrollment at Academia Del Pueblo was about 420 students. Today, enrollment is 300 students.

People were forced to move out of the area after the pandemic, he said, because rent subsidies were stopped.

“All of those families have been moved out of the downtown area, and they’re moving to far more affordable housing,” he said.

(Illustration by Sophia Biazus/Cronkite News)