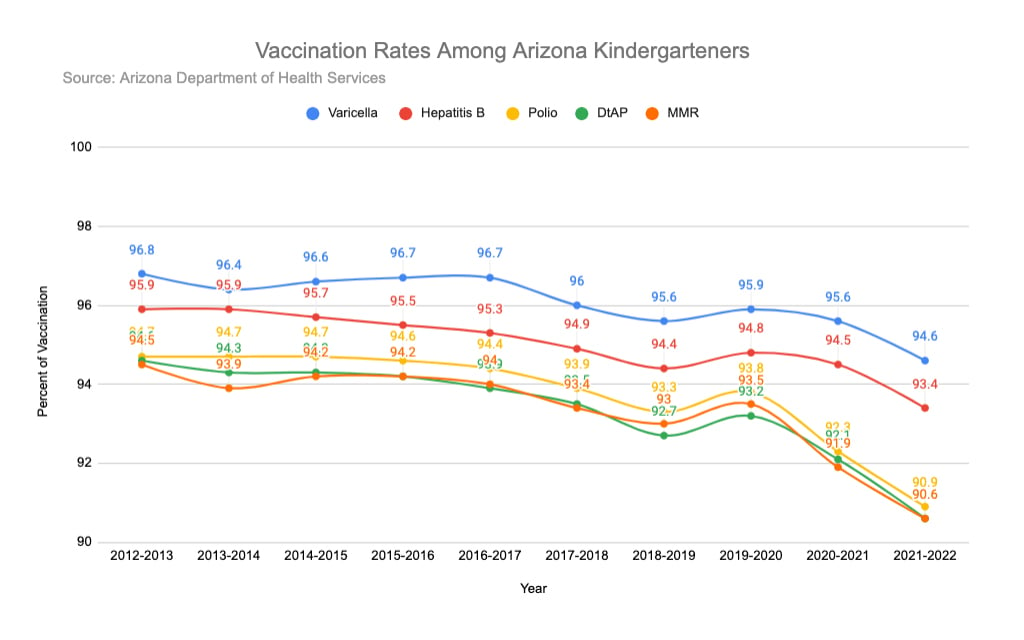

PHOENIX – Vaccination rates among schoolchildren in Arizona have steadily declined since 2012, but the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the drop across the state.

The trend is unlikely to reverse any time soon, which could result in serious health consequences for Arizonans in the future, experts fear.

Since 2020, routine preventative health care visits and vaccinations for kids have fallen 30% to 50% in Arizona, said Dr. Sean Elliott, who specializes in pediatric infectious diseases and is an emeritus professor of pediatrics at the University of Arizona College of Medicine. The drop occurred because doctor’s offices were shut down by pandemic precautions.

“There were no in-person health visits,” Elliott said. “Children were not coming to the pediatricians office for their routine care and vaccinations.”

But even as pandemic restrictions have been lifted, he said, parents still aren’t bringing their children to the doctor.

Arizona’s vaccination rates also have been depressed by misinformation campaigns about vaccines and a distrust in governments overseeing public health, which Elliott said deepened during and after the pandemic.

“Unfortunately, there continues to be the anti-vax movement,” he said. “Pre-pandemic, the rates of vaccines, the rates of uptake of science and the trust in health care professionals was already being attacked and was suffering.”

“The biggest concern, both at an individual level and at a societal level, is that growing up kids will be increasingly at risk for what used to be preventable pediatric illnesses – like measles and mumps,” Elliott said. “And the time to protect them with vaccines is in the first couple years of life. It takes their immature, brand-new immune system and gives it the exposure it needs to create lifelong protection.”

Although children can be vaccinated later, the risk for the most serious infections occurs within the first few years. Elliott also said immunocompromised children will be put at risk because Arizona has dropped below the herd immunity threshold of 95% vaccination rate.

(Data visualization by Cole Januszewski/Cronkite News)

“When we drop below a certain percentage of a community that is vaccinated, then those infections can gain a toehold and can create cases,” he said.

Arizona has seen recent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles and mumps, according to the state Department of Health Services. Elliott said health care providers and governments can take steps to stem the wave of anti-vaccination.

“The most important thing is to get kids and families back into their primary care provider’s office,” he said. “It is, thankfully, still true that most Americans trust their health care providers if they have an opportunity to listen to them and ask them questions.”

A 2016 study by the National Library of Medicine also found that “education is a key player” in getting children vaccinated. Some parents choose not to vaccinate their kids because of misplaced fears about the ingredients and side-effects of vaccines, the study said.

Another solution Elliott proposed is to limit religious and personal exemptions – which have ticked up since pandemic restrictions were loosened. Currently, the Arizona Department of Health Services says parents can opt to not vaccinate their children if they submit a signed ADHS Personal Beliefs Exemption Form testifying that immunizations are against their personal beliefs.

Even with government intervention, Elliott and the National Library of Medicine said, the most challenging and most important thing is to regain the trust of the American people.

“Healthy relationships between a practitioner and parent can go a long way toward helping patients” vaccinate their children, the National Library of Medicine study said. “Trust is paramount and will help put parents at ease and help them overcome unmerited fears.”

“No one is trying to hoodwink or hide information,” Elliott said. “If I am asked a question by a concerned vaccine hesitant parent, I am going to give them an honest answer but they have to ask the question.”