PHOENIX – A new research program combining the efforts of Northern Arizona University and the University of Washington aims to create a vaccine for Valley fever, an infectious fungal disease that poses an increasing threat as the climate continues to warm and dry.

“There’s no such thing as a vaccine for any fungal disease out there, and so we’re really going into entirely new territory,” said Deborah Fuller, a microbiology professor and vaccine specialist at UW. “If we’re successful, this would be a huge breakthrough … not just for Valley fever but for fungal diseases in general.”

Valley fever, scientifically known as coccidioidomycosis, mainly affects people living in Southwestern states. Its spores thrive in the soils of hot, dry climates and are small enough to be inhaled by humans and animals alike, causing an infection of the lungs.

Symptoms include fatigue, headache, muscle aches and cough. But because those symptoms are undiscerning, Valley fever can be misdiagnosed and incorrectly treated.

On average, some 200 coccidioidomycosis-associated deaths were reported each year from 1999 to 2019, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Among those most at risk for severe problems are African Americans, Filipinos, people with a weakened immune system, and women during the third trimester of pregnancy.

Chelsea Henry, 28, who lived in the Phoenix area in high school, learned she had Valley fever after suffering five weeks of debilitating fatigue. Eventually, she recovered.

“I was sleeping like 22 hours a day for over a month,” Henry said. “I ended up failing a lot of my classes because of it.”

It wasn’t until she got a chest scan for something unrelated that doctors found a calcification on her lungs and determined Valley fever was to blame for her exhaustion.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says Valley fever symptoms may become noticeable one to three weeks after a person inhales the spores, and they can last from a few weeks to several months.

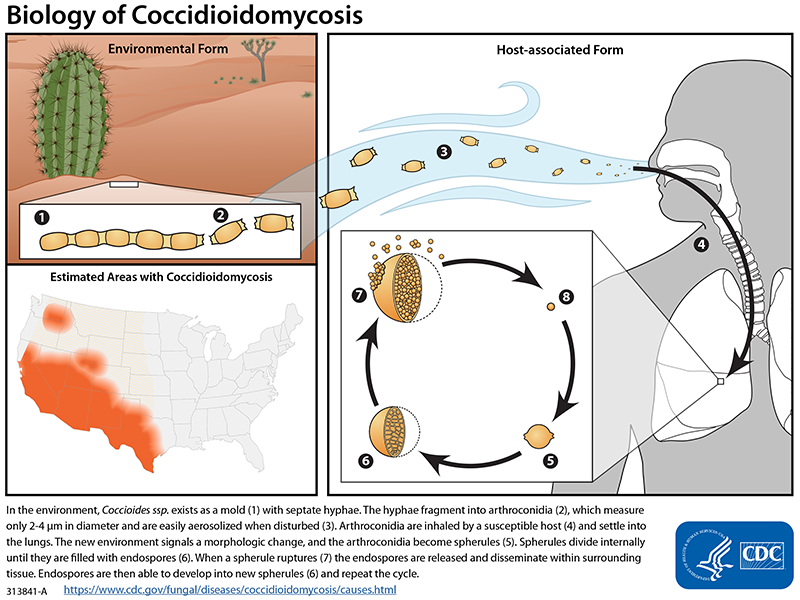

Researchers at Northern Arizona University and the University of Washington have teamed up to create a vaccine for Valley fever, a fungal disease that mainly affects people living in Southwestern states. Its spores thrive in the soils of hot, dry climates and are small enough to be inhaled by humans and animals alike, causing an infection of the lungs. (Graphic courtesy of the CDC)

Antifungal medications can control the fungus but sometimes don’t destroy it entirely. However, many people who have been infected develop a lifelong immunity to the fungus.

Bridget Barker, a biology professor at NAU, says public education about the disease in regions where Valley fever is endemic is crucial to proper treatment.

“Even in Arizona, where we have a high burden of disease, the likelihood of getting your diagnosis in a timely fashion is actually pretty low,” Barker said.

At this point, no completely effective treatment exists for Valley fever, but Barker’s team is on the hunt for a vaccine.

In September, NAU and a team at the University of Washington received a $1.5 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, with the potential to receive $7.5 million over the next five years.

The project includes launching the Virulence, Immunological Response, and Vaccine-Coccidioidomycosis Cooperative Research Center. The effort was spurred by a congressional mandate that the National Institutes of Health develop a vaccine for Valley fever in 10 years.

Because climate change is expanding the viable range for coccidioides spores to spread and grow, the NIH has recognized Valley fever as an increasingly urgent public health concern.

“This is really an emerging infectious disease of climate change,” said Fuller at UW. “Increased wildfires, increased dryness, heat and things like that are enabling greater spread of things in our soils.”

Fuller is one of the researchers responsible for spearheading the Valley fever project, bringing to the table her expertise in vaccine development. She has previously worked on HIV, influenza and even COVID-19, using nucleic acid vaccine technology.

This project is a vast departure from her previous work, Fuller said, given it’s the first time she’s tried developing a vaccine for a fungal disease.

Because coccidioides spores have a multistage lifecycle, Fuller’s team must create a vaccine effective against all. To do that, researchers will use Barker’s pathogenetic research to look for ways to inhibit the spores from developing or replicating.

Barker has been studying Valley fever for 20 years. Her research is based primarily in genome sequencing and learning about the ecology of the fungus. Between her understanding of the organism itself and Fuller’s expertise on vaccines, Barker said, the team has a good shot at success.

“There’s still a lot to do,” Barker said. “But I really think that at the end of this five years, we will have a candidate vaccine.”