TUCSON – Eighteen months ago, Ariel Enriquez found space for his five children at Park Place Condominiums in north Tucson. Soon after they moved in, the rent went up $200, to $1,700. With his struggle to pay the increase, the single father fell behind and was charged late fees, pushing his rent over $1,800. The family was evicted in April.

Enriquez, who’s an independent contractor, gathered his five boys and moved to a rundown apartment owned by a family member on Tucson’s south side, almost 14 miles away from the Park Place condominiums. A three-bedroom, two-bath unit at Park Place like the one Enriquez rented now goes for $1,800 a month, a $300 increase in less than two years.

“I’ve been in apartments that have gone up $70 or $80, maybe even $100 for a nice place. This one went up by $200,” Enriquez said. “I remember looking at apartments that were going for $700, $800 not even three years ago, and now they’re $1,300. Why in the world has the price gone up so much? It makes no sense.”

Rents are going up all over Arizona, as they are across the country, but Tucson, once considered sleepy and affordable, has seen a particularly painful spike. The median rent in Tucson in June was $1,795, up 30% from June 2021, according to Zillow data as of publication. And with rents rising, gentrification is pushing people out of neighborhoods that once were affordable.

“It’s been happening for a few years now. That’s when we saw the most people moving out of their neighborhoods,” said Betty Villegas, executive director of the South Tucson Housing Authority.

“And we saw it over and over again, people were priced out of natural occurring rentals. And the rents, you know, were starting to rise,” she added, referring to the usual supply of affordable housing in older neighborhoods.

The redevelopment and push for upscale housing has put particular pressure on west Tucson and downtown.

Older neighborhoods that traditionally were lower income and predominantly Hispanic are transitioning to market-rate housing, pressured by new developments in nearby areas, with apartments renting for as much as $3,000 a month. Residents of Armory Park, Menlo Park, the city of South Tucson and other communities are struggling to afford to live in neighborhoods where their families had settled decades ago.

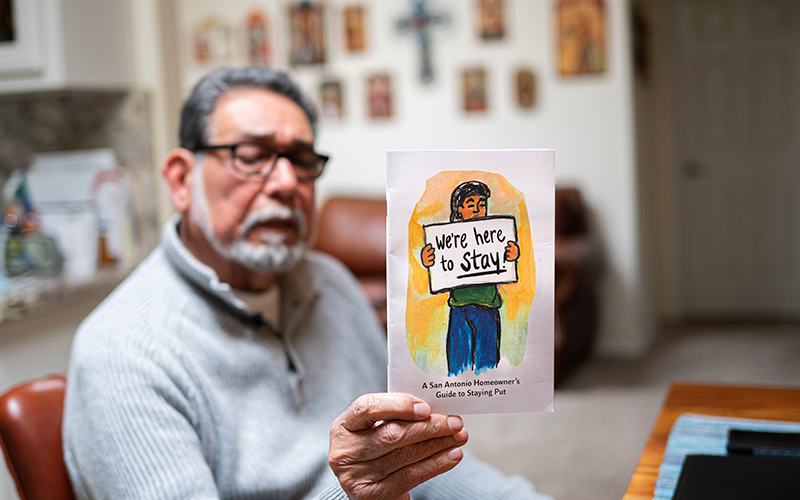

Raul Ramirez shows mock-ups that will become posters for the Menlo Park Neighborhood Association’s fight against gentrification. Menlo Park is home to mostly older, fixed-income Mexican Americans who settled there after World War II. Photo taken Feb. 28, 2022, in Tucson. (Photo by Genesis Alvarado/Cronkite News)

Menlo Park, less than a mile west of downtown, is a good example.

The area is home to mostly older, fixed-income Mexican Americans who settled there after World War II, said Raul Ramirez, vice president of the Menlo Park Neighborhood Association. But now the neighborhood has become a target for developers.

Interest especially increased after the SunLink Streetcar was completed in 2014. Menlo Park is on the streetcar’s last two stops, effectively connecting the neighborhood to downtown Tucson and the sprawling campus of the University of Arizona.

Students and young professionals have begun to move in, and the median rent there as of publication was up $689 over the past year, according to Zillow.

“Now they’re converting some of those apartments to market, the current market rate, so everything is super expensive,” Ramirez said. “And the people that are really being impacted then are folks that are renting.”

With a shortage of housing inventory, more developers want to build near downtown and take advantage of Tucson’s Government Property Lease Excise Tax, or GPLET, a tool that gives the city authority to grant incentives to build in particular areas. The city’s 10-year-old GPLET program subsidizes property taxes for up to eight years for projects in the Central Business District.

GPLET has “been used to bring new life to outdated, poorly maintained properties that were hotspots for crime, and now contribute to the economic growth of Tucson,” according to the Office of Economic Initiatives of Tucson.

Tucson has entered into 24 GPLET agreements, with some completed projects, including The Herbert, which converted an apartment complex for older people into luxury, market-rate housing. The Armory Park conversion was one of the city’s earliest GPLET projects, completed in 2013. Under the plan, the elderly residents were moved to another facility on the south side of Congress Street, which is downtown’s main drag.

One of the more recent GPLET projects is Union on 6th, an apartment complex only a couple of blocks west of UArizona.

Union on 6th is leasing for fall 2022, with studios starting at $1,315 a month and two bedrooms as much as $2,480, well above the median rent in Tucson. Amenities include a movie theater, pool and a clubhouse for residents.

But some worry that the projects are fueling the gentrification of old neighborhoods.

“Given all those incentives, you would think that they would be in a prime position to subsidize some low-income housing, but they don’t, it’s all market rate.” Ramirez said.

Kevin Burke, economic initiatives deputy director for Tucson, wouldn’t say whether GPLET projects are contributing to gentrification.

“The question was posed to the city, we have the folks come to the city and say, ‘These GPLET projects are causing gentrification,’ and we’re not going to sit there and say yes or no to that,” Burke said.

But he cited a 2021 study by Gary Pivo, a UArizona professor who studies sustainable cities and responsible property investing, on the equity and sustainability of the GPLET project in Tucson.

Pivo’s study found that GPLET projects were not the cause of gentrification, mainly because they constitute a small part of downtown development. However, it also said the GPLET program could do more to help people and businesses being displaced.

Raul Ramirez, vice president of the Menlo Park Neighborhood Association, discusses construction projects around Tucson on Feb. 28, 2022. Social workers say gentrification has hidden effects and stresses on families. People who stay have to put up with construction headaches. (Photo by Genesis Alvarado/Cronkite News)

Although the share of the Hispanic and Latinx population in the Central Business District, which encompasses most of downtown, fell by only 0.4% from 2012 to 2018, the years Pivo studied, the report said the decline was more significant in the traditionally Latino neighborhoods surrounding the district, including Barrio Viejo, Santa Rosa, Barrio Hollywood and parts of Menlo Park.

The report also said traditional mom-and-pop businesses are doing worse in the Central Business District than in other parts of the city or Pima County, probably from losing longtime customers displaced by higher rents.

The report said GPLET should look for opportunities to create affordable housing for people who earn less than $35,000 a year. For example, larger housing projects could provide some number of affordable units, and work with local affordable housing developers.

Since 2010, the Pima County Community Land Trust has provided homes to 111 low to moderate income families by remodeling or constructing on land purchased with money from donations and funding from Tucson and the county.

“Investors come in and are looking for these older neighborhoods … and the danger is it’s displacing people,” said Maggie Amado-Tellez, executive director of the trust. “Because right now, everyone, regardless of gentrification, everybody is in a financial bind – that they need to sell their home. Although they can get a good chunk of money, what house can they go buy? Where?”

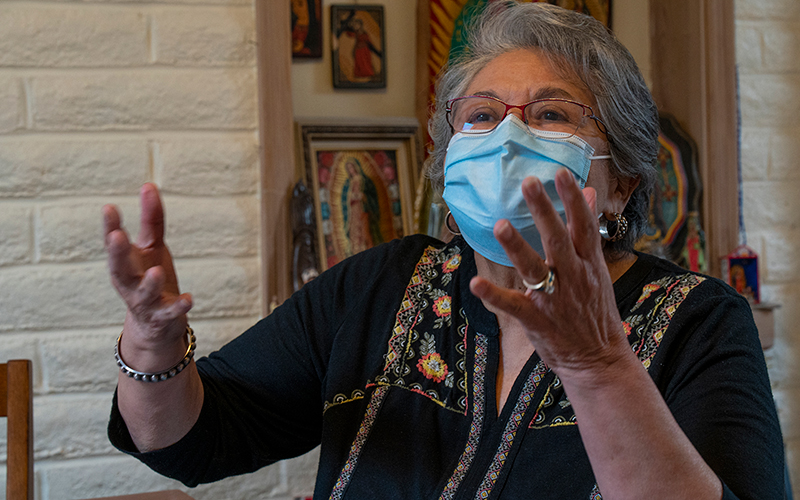

Monica Gutierrez, a Ph.D. student at the Arizona State University School of Social Work, said gentrification has hidden effects and stresses on families. People who stay have to put up with construction headaches.

“You have a lot of dust in the air going on, you have a lot of metals being cut, gases from the equipment that are being used to move the space and form the space into what it’s going to be,” Gutierrez said. “The city doesn’t think about ‘How are we going to protect the citizens around that?’ What are the policies in place to protect the citizens from those toxic fumes?”

People who leave lose their communities and have to travel farther for work, school and groceries, she added.

“We don’t think about displacement and the health effects of this work. And so while we can use gentrification as a buzzword, we need to dig deeper because it’s not just about gentrification,” Gutierrez said.

Since Enriquez’s family moved to the south side at the end of April, his five sons have been drastically affected. They will have to switch schools starting the next school year. In the meantime, the boys continued attending the same school, adding 30 minutes to their morning routine. And the spike in gas prices hasn’t been kind to Enriquez for the longer commute.

The new apartment’s air-conditioning is broken, the windows are old and it’s not insulated, making it hot inside during the day. Enriquez said his kids have been coughing a lot since moving in because of the dust, and no amount of cleaning has improved the situation. The family also has found mice in the apartment.

“I’ve been extremely busy trying to make the best of our situation,” Enriquez said. “The boys miss the much more comfortable apartment we were in and hate the abrupt move.”

The COVID-19 pandemic also has significantly affected renters in Tucson, especially working-class people and people of color, said Zaira Livier of the Tucson Tenants Union. Although the city introduced assistance programs for people who were affected by rent increases and displacement during the pandemic, she said, it’s difficult to get any actual help from these programs.

“We speak to folks all the time who are waiting on these things, and while they’re waiting on it, they’re still getting evicted,” Livier said. “Or they get their rent paid and the landlord still evicts them because that stuff doesn’t come with any strings attached for the landlord.”

The Tucson Tenants Union, along with Jobs for Justice Arizona and Casa Maria Soup Kitchen, organized a protest earlier this year against Monterey Garden Apartments for raising rents and pricing tenants out of their apartments. The majority of the tenants were low-income or under Section 8 housing, which uses government vouchers to help pay for private housing.

Roxanna Valenzuela, a volunteer for the Casa Maria Soup Kitchen, was surprised when she realized she couldn’t afford to move back into the South Tucson neighborhood where her family has lived since 1989.

“We started noticing that the makeup of the community started changing and it was becoming less affordable to find a house, rent a house, stay in the only community we knew to be our home,” she said.

Jesse Maison, a customer service representative who works from home, moved into the Villas de la Montaña apartments, near Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson’s east side, in July 2021. His one-bedroom apartment rented for $700 a month, Maison said, but since then, the complex has done repairs and renovations. For the remodeled units, rent rose $400 a month.

He’s paying the $1,100 for now but eventually will have to move out. He can’t afford it.

Cronkite News reporter Melissa Estrada contributed to this report.