TEMPE – When Julie Cart arrived at Arizona State in 1975, the women’s track program was barely a blip on the radar of the athletic department. The team trained with the men, sweating and practicing on the same field and at the same time.

“It was great for us to be around them, and it was great for them to be around us,” said Cart, who would become ASU’s first female discus thrower to win a conference championship. “We enjoyed being together, and there was this huge camaraderie.”

But that’s where the similarities ended. Female athletes didn’t have access to locker rooms at the track, Cart said. She recalls biking to and from the old gym to change in facilities that she calls “glorified bathrooms.”

“I would go to school and then change in the old gym,” Cart said. “Then I would ride my bike across campus to the track, and then back to my apartment. No showers, no nothing.”

That experience is a reminder, on this 50th anniversary of the passage of Title IX, of how different opportunities were for female athletes half a century ago.

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 bans sex discrimination in education programs and activities that receives federal funds. It opened the door to allow more sports participation for female athletes at all levels.

It didn’t take long for ASU women’s teams to find success. The Sun Devils won 18 titles in its early governing bodies – the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, and the Division for Girls and Women’s Sports – and 13 team championships, including eight in golf.

Victoria Jackson, a sports historian and clinical assistant professor in Arizona State’s School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, said in many ways ASU was a leader before the passage of Title IX.

“Women’s physical education instructors Nina Murphy, Anne Pittman, Mary Littlewood and Mona Plummer hustled to create competitive, elite sporting opportunities for college women who craved elite competition,” she told ASU News. “This meant working 12- or 15-hour days for little additional pay; coaching or refereeing after a full day’s work of teaching and advising; holding bake sales; sewing uniforms; pooling resources to pay for one hotel room for the whole team; and piling everyone into a student’s station wagon to drive to California for a competition.

The road wasn’t always easy.

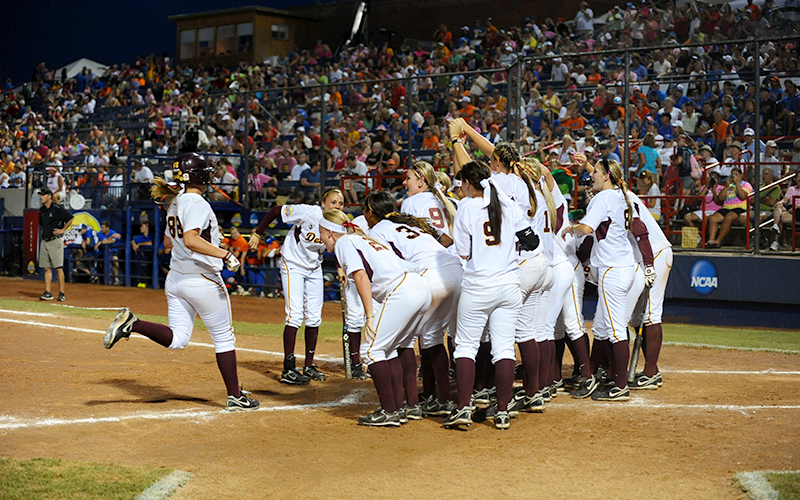

In 2011, Arizona State captured the Division I Women’s Softball Championship by beating Florida in the Women’s College World Series (Photo by Joshua Duplechian/NCAA Photos via Getty Images)

When the ASU Activity Center was built in 1978, the women’s track program was afforded the same level of facilities as the men’s. For the first time, Cart and her teammates had access to the weight room at the athletics facility and such amenities as locker rooms, trainers, a steam room and even a snack bar. For Cart, by then an upperclassman, it was eye-opening.

“We got to see how the other half lived,” she said.

The steam room was a particular object of fascination. The women would enter the room and immediately feel as if they were on equal footing with the male athletes. Something about that sanctuary of steam blurred the lines between genders and created an almost ethereal environment, Cart said.

“Being in a sauna is a really good way to relax post-workout,” she said. “There’s an equitability when you’re in those kinds of settings.”

One person they routinely encountered in the steam room was head football coach Frank Kush. A strict disciplinarian, Kush was welcoming, if not warm, within those four walls. The women often would be greeted with a smile, and a sense of peace.

“He was very welcoming,” Cart said. “I don’t know if he thought it was cute or what, but here was this normally scowling figure saying, ‘How are you two doing?’”

The rest of the football team wasn’t so hospitable. Despite having their own weight room on campus, football players routinely used the one for track athletes, perhaps to use the bench press or simply to make their presence felt.

“They felt like they owned the place,” Cart recalled. “And quite frankly, they did.”

Cart refused to remain silent on the issues faced by track athletes and women in the athletic department. In a letter addressed to former athletic director Fred Miller, which she says now is lost, Cart implored the department to support her cause. Cart went on to a journalism career that, in 2009, was capped with a Pulitzer Prize in reporting.

“We were reminded fairly regularly that we weren’t at the top of the club,” Cart said. “Football is at the top, baseball and basketball are there, and then the rest of us.”

Scandal in the sun

The era of mullets, leg warmers and the Sony Walkman also was one of turmoil in the Arizona State athletic department. In the first five years of the 1980s, the school saw three athletic directors come and go, as well as the conclusion of an investigation into the storied football coach, Kush, who had been fired in 1979.

It was also an era of change. Title IX had been passed in 1972 but was just beginning to truly change the landscape of college sports. At universities across the country, there was still a strong undercurrent of inequity in and around the athletic programs.

Linda Vollstedt, ASU women’s golf coach, was working out of a small office in the basement of Activity Center (now known as Desert Financial Arena) while her counterpart on the men’s side, Ron Rhoades, was positioned on the main concourse. Vollstedt, then a part-time employee, earned $8,000 to Rhoades’ nearly $40,000.

“We didn’t have the same opportunities or the same funding,” said Vollstedt, who would lead the Sun Devils to six national championships in women’s golf in the 1990s. “It was just different back then.”

Although women’s sports certainly received more attention and resources than they had in Vollstedt’s time as an ASU athlete in the 1960s – when the women had to purchase their own golf balls and practice on a dirt patch behind the student fitness center – support in the early 1980s still lagged that of the men’s programs. In the summer, Vollstedt would pay for recruiting trips out of her own pocket and wasn’t eligible to be paid for the time she spent tracking down the next generation of Sun Devil golfers.

To his credit, Rhoades encouraged Vollstedt to go to human resources and campaign for more resources. But at the meeting, Vollstedt recalled, she was told, “Honey, that’s just the way it is, and you just have to accept it.”

Linda Vollstedt, front right, and the Arizona State women’s golf team celebrate before winning the NCAA Women’s Division I Golf Championships in Columbus, Ohio, in 1997. The Sun Devils have won eight titles. (Photo by James Sabau /Allsport via Getty Images)

Forging on

Despite the inequity, some female athletes still managed to thrive.

As discus throwers on Arizona State track and field team, Leslie Deniz and and Ria Stalman were no strangers to competing in Los Angeles, which is home to a pair of Pac-12 schools, UCLA and USC. But on Aug. 11, 1984, Deniz and Stalman were in L.A. competing not as Sun Devils but as members of their respective Olympic contingents, the United States and Netherlands. Deniz and Stalman finished with silver and gold medals, respectively, marking a first in Arizona State women’s athletics.

Both Deniz and Stalman had been three-time All-Americans in Tempe, their seasons overlapping in 1981. Deniz, who grew up in Gridley, California, north of Sacramento, set a national high school record in discus with a throw of 172 feet, 11 inches. Her three All-American seasons for the Sun Devils (1981-83) culminated in a national championship in ’83 with a throw of 209’10”.

Stalman, from Delft, Netherlands, already was in her late 20s when she arrived in Tempe in 1978. She was a highly decorated Dutch national champ, winning 15 gold medals from 1973 through 1983 in discus and shot put. Her All-American seasons in Tempe took place from 1979-1981, the final year ending with a national championship throw of 198’3”.

Stalman and Deniz made their marks, physically and metaphorically, on Sun Angel Field. Stalman already had attended Grambling and the University of Texas-El Paso, and Cart had noticed her at meets. When UTEP’s coach departed, Cart did some unofficial recruiting on behalf of her school – well aware that Stalman would replace her as ASU’s top women’s discus thrower.

“I wasn’t happy that Ria came to ASU because before that, I was the best discus thrower at ASU,” Cart said. “I realized, though, that I got better because Ria came. I’m sure Leslie felt the same way.”

Olympic toss off

On Aug. 11, 1984, Deniz and Stalman found themselves on the infield at the Los Angeles Coliseum for the women’s discus throw final. Another competitor, who would finish fifth, was Meg Ritchie, a Briton who had attended the University of Arizona and had battled Deniz and Stalman often.

Cart was up in the press box, covering the competition as a staffer for the Los Angeles Times. Also there was ASU throwing coach Roy Aguayo, but he was moonlighting as a security staffer for the Olympics, part of a detail referred to as “the flying egg.”

“There’d be four of us around the athletes like an eggshell,” Aguayo said of his job of escorting high-profile athletes to meet the world press. “It was a lot of fun.”

Although Aguayo was off-duty that afternoon, he lingered in the tunnel that led to the track. There, he reprised his role as coach.

In the early years, opportunities for women in sports were limited, especially at the collegiate level. Title IX helped change that. (Photo courtesy of Getty Images)

“They’d come and look at me to see what they needed to do,” he recalled. “Back then you couldn’t communicate verbally, so we had little gestures which meant certain things. I was there as security, but I was off-duty, so I was just there to watch.”

As Stalman and Deniz went back and forth, each woman besting the other on each ensuing throw, Cart bit her tongue.

“I wanted to (cheer for them), but no cheering in the press box,” Cart said. “It was nerve-wracking for me. You also want to shout down and say ‘You’re dropping your arm’ or whatever. It was really cool to watch because I knew the work they put in.”

The final itself was dramatic. Deniz and Stalman exchanged first place on all six throws. Deniz’s fifth put her in the lead over Stalman by .36 meters, with the Dutch record-holder yet to record her ultimate mark.

As Stalman prepared, Cart, Aguayo and a Coliseum full of fans waited. When Stalman’s final throw topped Deniz by half a meter, the stadium erupted. Aguayo recalls that moment and the emotion overwhelming him. He leapt over the rail and joined his former ASU athletes on the field in a group hug.

“They were both crying,” Aguayo said. “It was incredible. All that hard work and frustration over time, it was almost a relief it was over for them.”

Stalman retired shortly after winning Olympic gold. Deniz, the silver medalist, would go on to a career in law enforcement in California.

The controversy

It soon became clear that with the move toward equality, women were under more pressure to succeed.

On Aug. 23, 1994 – 10 years after the Olympic discus final – reporter Elliot Almond wrote a story in the Los Angeles Times that had major implications. In the piece, to which Cart contributed, Almond alleged a major doping coverup during the ’84 Games. The piece cited whistleblower Don Caitlin, the director of the facility at UCLA, which handled the testing of the athletes, alleging that numerous positive results were never reported.

In a 2016 interview with Dutch television program Andere Tijden Sport, Stalman acknowledged using a “small, daily dose of anabolic steroids” during the last two and a half years of her career. She mentioned a desire to keep up with the Soviet bloc athletes she was competing against.

“During the warmup, you see all those refrigerators walking around, and they kicked my ass with 15 meters difference,” Stalman said, “So, I thought, ‘What can I do to beat them at the Olympics?”

Stalman’s reputation took a major hit following her admission. Although she remains credited as an Olympic medalist, she was stripped of her Dutch record of 71.22 meters. Once an idol to Dutch athletes, Stalman has become a pariah to many.

Aftermath

In the years that followed that fateful final, women’s athletics have received markedly more attention. Ritchie, now Meg Stone, went on to become the first female strength coach for the UArizona football team.

Stalman and Stone remain close, with Stalman even participating in the Scot’s wedding. Stalman also remained close with Cart for many years. Cart remembers visiting Stalman’s family in Netherlands and training with her club for a time. Aguayo, too, visited Stalman in Europe in a momentous occasion for the storied coach. Meanwhile, Deniz became a California Highway Patrol officer and now teaches at Woodland Community College.

This story does not have a decidedly Disney ending. Stalman’s doping acknowledgement badly marred her reputation.

“She decided she was tired of lying,” said Cart, who doesn’t think Stalman deserved the backlash she’s received.

“I give her a lot of credit. People will look at it and compare it to Lance Armstrong, but I know what happened and how long she resisted that. She wasn’t taking drugs throughout her whole career.”

Despite Cart’s defense, Stalman has fallen on hard times. Her website, rstalman.nl, has been taken down and the email provided by Cart (which is tied to that domain) appears to have been disconnected. She’s also no longer listed on the Eurosport website, where she worked as a commentator, and attempts to contact her turned up empty.

Her legacy, though, lives on. A true pioneer for women’s athletics at Arizona State University, Stalman’s legendary Olympics duel with Deniz in 1984 is a testament to their dedication and remembered as one of the greatest athletic achievements in ASU history.