PHOENIX – Doctors, nurses and other health care workers across the country have reached crisis levels of burnout, prompting the U.S. surgeon general to urge employers to review workloads and take further steps to address well-being.

Health care burnout isn’t a new phenomenon, but it is escalating. The National Academy of Medicine found that even before the pandemic, burnout affected 35% to 54% of nurses and physicians, while 45% to 60% of medical students reported symptoms.

COVID-19 made a bad situation worse, as health workers faced long hours, a crush of critically ill patients and added risks to their own health and that of their families. A Mental Health America survey conducted early in the pandemic from June through September 2020, found that 93% of health workers experienced stress, 86% reported anxiety, 76% reported exhaustion and burnout, and 41% reported loneliness.

Experiences of burnout differ from person to person but generally consist of work-related stress, emotional and physical exhaustion, and dissociation from patients or loved ones. Anxiety, depression or substance abuse can follow, bringing risks to patient care or missed work.

Experts worry that the health workforce, under increasing demands with fewer resources, will continue to diminish faster than it can recover.

“Health worker burnout is a health crisis for all of America, and that is why we need to treat it like a national priority,” said Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, who last month issued a national advisory bringing attention to the problem. Murthy recalled meeting with a Florida nurse who said the pandemic had left him “helpless but not hopeless.”

In May, Murthy and Dr. Rachel Levine, assistant secretary for health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, held a roundtable discussion at the Phoenix Indian Medical Center to hear experiences from local health workers and members of the Indian Health Service.

“These heroes deserve more than our gratitude; they deserve our help,” Levine said. “We’re here to tell health care workers: We hear you, we see you, and we’re here to help you.”

Dr. Claire Nechiporenko, a pediatrician at the medical center who previously worked on the Navajo Nation, said addressing burnout is vital to prevent further workforce reductions, especially in underserved communities.

Research shows that more doctors and nurses are either limiting work hours or intend to leave their practices, and the Association of American Medical Colleges estimates a shortage of 37,800 to 124,000 physicians by 2034.

Rural areas would be among those hardest hit by a shrinking workforce – including Arizona’s Indigenous communities, which already face deep health disparities and trouble accessing care.

“Even pre-pandemic, we’ve had health care shortages on reservations,” Nechiporenko said. “It’s difficult to get physicians – any type of health care worker – to work remotely, and most of the time it’s an environment where they’ve never been.”

During the pandemic, health workers in rural communities have been subjected to irregular and long hours, more isolation, an expectation to always be on call, and lower pay, studies show.

Beyond differences among urban and rural health workers, gender may also play a role in burnout. The National Academy of Medicine reports that burnout may be 20% to 60% more likely in female doctors than male doctors.

Vivek said it’s not solely the role of the health care industry to fix the problem. Government officials, community advocates, academic institutions and leaders in technology must come together to help the profession thrive once again.

In January, the Department of Health and Human Services announced $103 million would go toward evidence-based training programs and practices to improve mental health among health workers and help build resiliency.

The surgeon general’s national advisory also calls on employers to enact paid leave, rest policies, and strengthen existing policies that protect health workers from community and workplace violence.

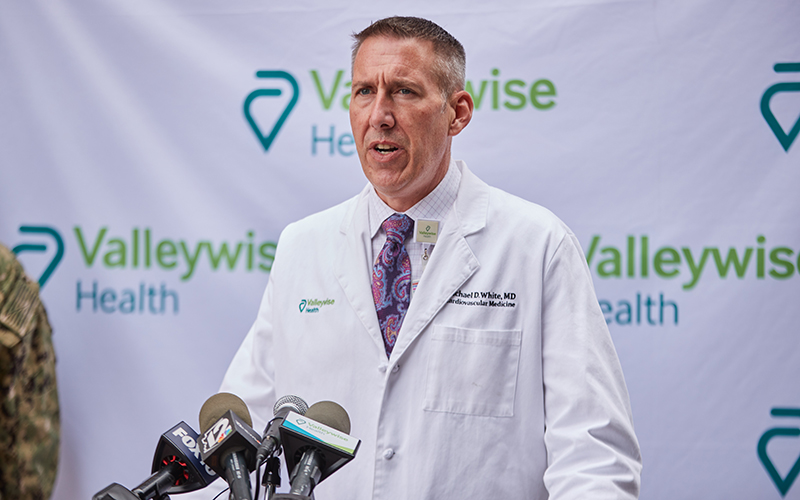

Surgeon General Vivek Murthy joined Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary Rachel Levine, left, last month at the Phoenix Indian Medical Center to highlight burnout among health care workers and its dangers. (Photo by Alexandra Conforti/Cronkite News)

Additionally, it calls on medical schools to intervene to prevent stress among students, introduce inclusive and communal wellness programs, and establish schedules that reduce sleep deprivation.

In Arizona, health care systems and hospitals have supported workers amid the pandemic with check-in calls and more days off. Banner Health created “respite rooms” to allow workers to remove protective equipment and take time to rest and recharge in rooms filled with snacks, games, music and special lighting.

In 2020, Gov. Doug Ducey announced the state would spend $25 million to reinforce hospital staffing and allow facilities to reward frontline workers with bonuses for their efforts.

However, in December 2021, over 1,000 health care professionals in the state sent a letter to Ducey and other state officials arguing the system was still in crisis and petitioning for assistance in slowing the spread of COVID-19.

Nechiporenko, who works with several hospitals in Phoenix, said it’s important for managers to give workers the breaks they deserve to address ongoing issues with burnout.

“I really try to give everybody the time off that they request, because that’s their time and they earned it and they deserve it,” she said. “If you can be a leader … where you can give your employees … that time to be away from work and kind of get recharged to come back, I think that’s huge.”

Sticking to a solid routine and engaging in outside activities can also help health workers maintain a work-life balance and gain relief from burnout, Nechiporenko said, adding that she does crossfit to reduce stress.

“The burnout’s the same anywhere and everywhere,” she said. “It’s going to start with first taking care of yourself before you can take care of others.”