The Phoenix Housing Department is one of more than 20 public housing authorities in the state. Federal officials in April directed authorities across the country to review their policies and propose updates within six months to any rules that “pose barriers to housing” for people with criminal backgrounds. (Photo by Lisa Patel/Howard Center for Investigative Journalism)

PHOENIX – As they look for a place to live in Arizona’s overheated rental market, applicants with criminal backgrounds seeking government-supported housing face hurdles that go far beyond what federal guidelines require.

That’s because the housing authorities that provide these resources have used the wide discretion afforded them by the Department of Housing and Urban Development to establish rules that look back further into the applicant’s past, consider a wider swath of crimes for denial and often move beyond convictions to arrests or warrants, a Howard Center for Investigative Journalism analysis has found.

HUD has urged public housing authorities to move away from strict “one strike and you’re out” rental policies. But it has done little to check that its guidance on criminal background checks is being followed. And HUD also hasn’t required those authorities to track data that might demonstrate whether their housing denials have a disparate impact on communities of color.

Khalil Rushdan, who spent 15 years in prison before his wrongful conviction was overturned in 2011, now serves as the organizing director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona, where he helps people with criminal backgrounds reenter society.

“After someone has paid everything, has fulfilled their obligations, you are still being punished and you’re still being targeted by the state by these policies, which becomes another barrier,” Rushdan said. “I’ve seen over the years where people just give up, because they say, ‘Hey, I’m trying to do what’s right – and then I’m still being punished because I can’t get a place.’”

Social scientists have found that homelessness, frequent moves, evictions and even challenges paying rent – all aspects of housing instability – can harm people’s economic standing and their health. Research shows housing instability also can increase the risk that formerly incarcerated people will reoffend.

And the ripple effects can extend to family members.

Close to half of all U.S. children have at least one parent with a criminal record, according to a report from the Center for American Progress, a national public policy research and advocacy group. Stable housing is crucial to children’s overall well-being. Research shows their development, their mental and physical health, as well as how they do in school, all are affected by housing instability.

A 24-story building goes up in downtown Phoenix, one of many construction sites across the fast-growing city. As Arizona’s population continues to swell, access to housing has become more difficult in the past few years, particularly for renters with criminal backgrounds. (Photo by Lisa Patel/Howard Center for Investigative Journalism)

Rushdan considers the criminal background checks by Arizona housing authorities to be an extension of an “overall punitive culture” in the state, whose incarceration rate per 100,000 people is higher than some countries, including the United Kingdom and France, according to a data analysis from the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative. And communities of color often are uniquely damaged by these policies.

The barriers criminal background checks pose to housing take on an increased significance as Arizona faces an affordable housing crunch and a growing population of people experiencing homelessness. But the state’s problem isn’t unique.

The federal government provides funding and technical assistance to more than 3,300 public housing authorities, which in turn help more than 4 million households across the country. Many authorities have stricter admission rules than HUD requires, according to a 2020 study published in the American Journal of Public Health that looked at criminal background check policies in large cities.

Recognizing this widespread impact, HUD issued a notice in early April calling on public housing authorities to review their rules and propose updates within six months to any that could “pose barriers to housing” for people with criminal backgrounds.

Those changes are expected primarily to affect assistance provided under HUD’s two largest housing initiatives: the Public Housing Program and the Housing Choice Voucher Program, commonly known as Section 8. Most public housing units are owned by local housing authorities, while the voucher program helps applicants seeking housing from participating private landlords.

While housing authorities may continue to look at criminal backgrounds as part of their approval process, HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge urged them to implement policies rooted in community safety but that also “treat people as individuals rather than reducing them to their criminal histories.”

Some providers had taken such steps, Fudge said in an April 2022 memo, but “too many continue to exclude people from desperately needed housing opportunities based on events that have little or no relevance to fitness to be a tenant.”

‘Zero tolerance’

In the late 1990s – in the aftermath of the federal government’s “war on drugs” – HUD Secretary Andrew Cuomo declared illicit drugs in public housing as “public enemy No. 1.”

“We must have zero tolerance for people who deal drugs,” he said. “They are the most vicious, who prey on the most vulnerable. They are the jailers, who imprison the elderly. They are the seducers, who tempt the impressionable young. They must be stopped.”

The government’s “one strike” initiative required public housing authorities to amend their policies to screen out applicants who were using illegal drugs and abusing alcohol. Six months after it was implemented in 1997, responding public housing authorities had denied nearly double the number of applicants with criminal backgrounds, according to a HUD report at the time. And the number of drug-related evictions also spiked, from nearly 2,700 to almost 3,800.

The federal government characterized the initiative as a success, but by 2011, its tone had shifted significantly.

In a memo to public housing authorities, the Obama administration’s HUD urged a less aggressive approach toward people with criminal backgrounds, stressing the importance of “second chances” after people had “paid their debt to society.”

In the decade since, housing authorities in Arizona have been relatively slow to change their policies, according to a Howard Center analysis. The center examined all policies released by 20 of the state’s nearly two dozen public housing authorities. But some authorities did not turn over all of their documents – although the records are supposed to be public – and housing authorities in Williams and Eloy declined to make any of their policies available despite multiple requests.

HUD provides funding and technical guidance to housing authorities and requires them to deny applicants with certain criminal backgrounds. They must bar anyone who has been evicted from federally assisted housing in the previous three years for drug-related criminal activity, as well as anyone who is using illegal drugs, subject to a lifelong sex offender registration or has ever been convicted for manufacturing methamphetamines in federally subsidized housing.

For all other crimes, HUD lets public housing agencies decide whether to deny applicants — and they’ve taken a variety of approaches.

Authorities in Mohave County, in Arizona’s northwest corner, and the southern border community of Nogales generally deny applicants to its Housing Choice Voucher program who have any history of drug use or criminal activity within the past five years, according to a review of their policies. Exemptions are possible based on circumstances, such as for applicants who provide evidence of successful rehabilitation.

At least four other housing authorities also look back five years for some other criminal activities – and nearly all the policies the Howard Center analyzed go beyond HUD’s 2015 statement that a best practice for “look back” periods would be a year for drug crimes and two years for violent crimes.

The center’s analysis also found that at least 15 housing authorities, including those in Nogales and Mohave County, continue to examine arrests as part of their criminal background checks, even as HUD has begun moving away from these.

An arrest shows “nothing more than that someone probably suspected the person apprehended of an offense,” HUD wrote in a 2015 memo, which advised housing authorities to no longer use arrests as a sole reason for denying an application. The majority of public housing authorities that do consider arrests state that they only look at them in conjunction with convictions and evictions. However, some Arizona nonprofits have taken issue with their continued use.

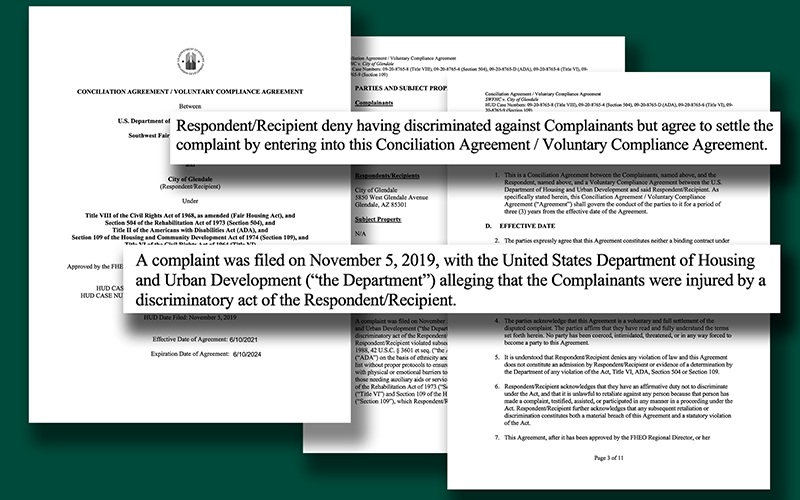

The William E. Morris Institute for Justice in Phoenix filed a complaint with HUD in 2019 over the city of Glendale’s use of arrests in eligibility decisions and evictions, said Brenda Muñoz Furnish, a staff attorney with the nonprofit institute.

Several Arizona nonprofits filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development against Glendale in November 2019 over concerns about the handling of its waiting list for government-subsidized housing. The city has implemented several policy changes, including how criminal records are used in the housing application process. (Graphic by Jessica Alvarado Gamez/Howard Center for Investigative Journalism)

“It’s our position that arrests should not be used at all,” she said in an interview. “And we also think that a very limited look-back period should be used if criminal convictions are being used at all.”

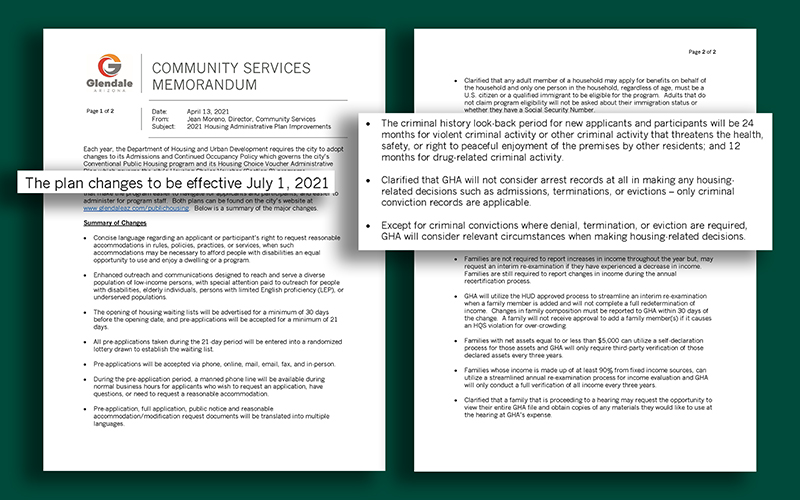

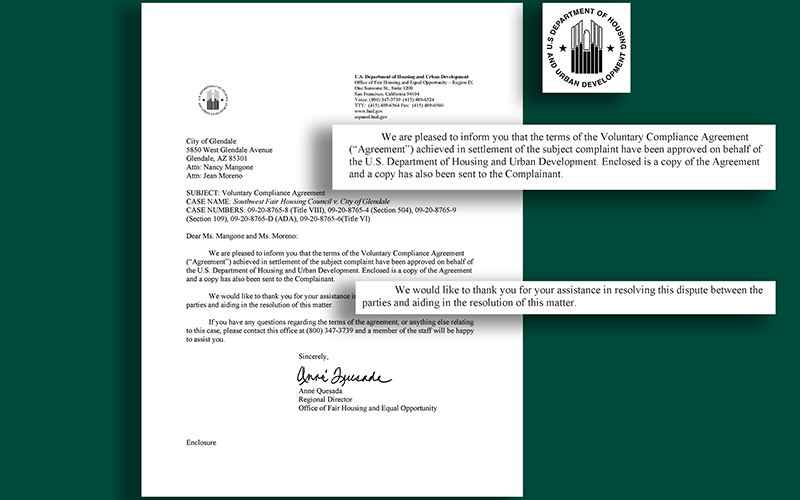

After receiving the complaint, Glendale stopped looking at arrests and changed some of its other criminal background rules. It now is the only one of the nearly two dozen housing authorities in Arizona included in the Howard Center’s analysis that’s following HUD’s guidance on limited look-back periods for violent crimes and drug offenses.

Jean Moreno, who became Glendale’s community services director shortly after the complaint was filed, said the changes better align the housing authority’s policies with its ultimate aim – to provide housing as a tool “to change people’s lives.”

“My philosophy is we’re not going to overregulate something,” she said, “because our goal is we want to make sure that we can reach as many people as possible with our programs.”

The people who work within housing authorities are “good people,” Moreno added, who “want to make a huge difference in their communities.” But in such a highly regulated environment, change can be slow.

“What if we allow somebody into our program that had a violent criminal history five years ago, 10 years ago?” Moreno asked. “What if we allow them into our program and they hurt somebody?”

Several Arizona nonprofits filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development against Glendale in November 2019 over its waiting list for government-subsidized housing. The complaint resulted in several policy changes, including how criminal records are used in the housing application process. (Graphic by Jessica Alvarado Gamez/Howard Center for Investigative Journalism)

‘More enforcement’

HUD historically has exercised limited oversight over its regulations, leaving nonprofits like the Morris Institute to push for changes to criminal background policies used by housing authorities.

An August 2018 report from the Government Accountability Office noted that HUD did not “routinely monitor” housing authorities’ compliance with federal requirements on criminal history policies. The congressional watchdog agency recommended that HUD take a greater role to ensure its guidebooks for housing authorities reflect current federal guidance.

In November 2019, HUD made updates to its guidebook for the Housing Choice Voucher program. But as of March 2022, it had not updated its guide for public housing programs, according to the Government Accountability Office.

Jay Young, executive director of the Southwest Fair Housing Council in Tucson, said some housing authorities either are unaware of or don’t understand HUD’s guidance on background checks.

“Or if they do know the guidance,” he said, “they really don’t pay any attention and still make it much harder than really it should be for people with criminal backgrounds to find housing.”

Although the federal government has recognized the disproportionate impacts criminal background checks have on communities of color, several experts said HUD does not require housing authorities to report specific demographic data on applicants they deny. And that lack of information severely limits efforts to track inequity within the federally assisted housing system, experts say.

“We should be required to report that – and HUD should be monitoring that – in my opinion,” Moreno said.

People of color are particularly affected by background check policies because this population more often is overpoliced — meaning an increased likelihood they will be “arrested, detained, convicted and imprisoned” compared to “similarly situated white individuals,” according to a research study published in Housing Policy Debate in 2017 that examined the impact of criminal history reviews in public housing.

“My opinion is that any policy that is excluding someone on the basis of criminal record is going to have a disparate impact,” said Danya Keene, associate professor of social behavioral sciences at the Yale School of Public Health who researches housing policy. “Even if you are enforcing that policy equally, that is a racist policy.”

HUD acknowledged in 2016 that strict criminal background policies can be discriminatory, given systemic racial disparities in the criminal justice system. They can even violate the Fair Housing Act if their burden “falls more often” on applicants of one race over another.” People with criminal records are not a protected class under the act, which prohibits discrimination in housing based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, disability or familial status.

Concerns about the disparate impact of criminal background check policies on communities of color were part of what prompted the federal government in April to direct public housing authorities to reassess their rules.

Applicants who are denied on the basis of a criminal background check can file a complaint with their public housing authority and are entitled, in most cases, to an informal review process in which their grievance is documented and investigated.

The Howard Center requested data on these complaints, but the vast majority of Arizona’s housing authorities declined to provide the information, said they did not have the information, or did not respond to the center’s requests.

Rushdan, the ACLU organizer, said Arizona’s criminal background policies greatly affect communities of color.

Black people are far more likely to be incarcerated in Arizona than any other race or ethnicity, according to 2010 data from the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit that researches mass incarceration and criminalization.

But without proper federal oversight, Rushdan said, housing authorities have no fear of consequences for policies that unfairly affect communities of color.

“I think there needs to be more enforcement from HUD,” he said. “There should be an incentive to do the right thing. And if you can’t do the right thing, then there needs to be some fines or something.”

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development recently approved a voluntary compliance agreement among Glendale and several nonprofits that had filed a complaint about the city’s housing policies, including to its use of criminal records in the application process. (Graphic by Jessica Alvarado Gamez/Howard Center for Investigative Journalism)

If you or someone you know is facing housing discrimination or believe your rights have been violated, you can file a complaint by calling HUD at 1-800-669-977 or visiting the How to File a Complaint page on HUD’s website. You can also contact a fair housing organization in your area.

This story was produced for the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, an initiative of the Scripps Howard Foundation in honor of the late news industry executive and pioneer Roy W. Howard. Contact us at [email protected], visit us on Twitter @HowardCenterASU.