PHOENIX – Maria Parra Cano clearly recalls the moment she decided to help craft the 2025 Phoenix Food Action Plan, whose five goals include healthful food for everyone and strengthening the local economy.

In fall 2018, Cano was at the Maryvale Community Center in west Phoenix to talk about amaranth, an ancient grain with medicinal properties, when a mother asked where she could find it.

“This is a problem because I shouldn’t have to go to six different places just to put this food on the table,” Cano remembers telling the group. “You can only find amaranth like this at Whole Foods, and there isn’t one close by.”

Cano, 40, a Phoenix native of Mexican and Indigenous roots, has made a living preparing traditional Indigenous foods to heal and treat the body. In 2018, she founded Sana Sana Foods, which promotes “Food medicine for the people.”

Today, she’s one of the developers of the 2025 Phoenix Food Action Plan, which includes specific efforts for south Phoenix. The plan promotes local food systems and strives to create healthy communities south of the Salt River, a part of Phoenix that’s largely made up of people of color, many with immigrant roots.

In 2017, the Phoenix Office of Environmental Programs applied for assistance through the Local Foods, Local Places program, which is funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The goal was to develop a food action plan that would promote healthful living and increase economic opportunities for local farmers and businesses.

Amelia Garcia grows her own food and encourages her neighbors in south Phoenix to do the same. (Photo by Scianna Garcia/Special for Cronkite News)

The food plan’s developers are a diverse group of women, all from different community organizations and backgrounds, but with some kind of connection to south Phoenix.

For Cano, this connection came from catering meals for Sana Sana.

Amelia García, who’s also part of the group, took her own approach, the South Phoenix Healthy Start and Backyard Food Farm. For her, contributing to the action plan means more than just giving her family a source of healthful food.

“If we focus more on the foods we eat, we will change health outcomes, infant mortality rates and crime rates, simply by changing our eating habits,” she said.

South Phoenix is widely known for its rich agricultural land use and has a history of environmental justice concerns because of structural racism. However, over the years, in this and other parts of metro Phoenix, agricultural production has declined substantially. Acres of cropland have been replaced by miles of auto salvage yards and manufacturing, according to the Phoenix Food Action Plan.

More than 75% of Maricopa County is considered a “food desert” or “food apartheid,” according to the Phoenix Office of Sustainability, “where residents are more than one mile from fresh and healthy food.” South Phoenix falls into that category.

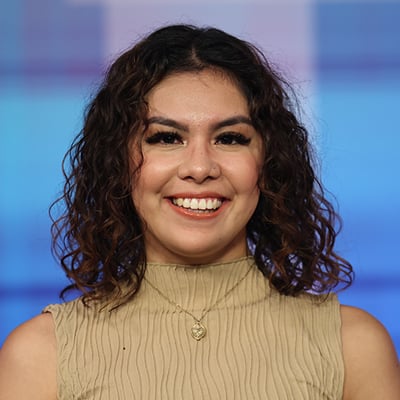

Maria Parra Cano of Sana Sana Foods prepares burritos with all-natural ingredients for food packages she sends to food-insecure people in south Phoenix. (Photo by Reyna Preciado/Special for Cronkite News)

According to The Pew Charitable Trusts study “South Central Neighborhoods Transit Health Impact Assessment,” south-central Phoenix has only seven grocery stores within a half-mile of Central Avenue from Broadway to Baseline roads.

Isabel García, a caseworker for Child Crisis Arizona and a south Phoenix resident who also contributed to the food plan, said such factors as the cost of transportation are big contributors to the problem of food inaccessibility. This disparity is just one example of how south Phoenix has been deprived for decades, she added.

“We have been intentionally kept out because of racism and systemic oppression, we have been kept away from healthy food, and the big supermarket chains have no incentive to come into south Phoenix,” García said.

Cano’s passion for ancient Indigenous foods is what led her to join the plan, and why she continues to serve the people of south Phoenix. She initially was the caterer for the planning meetings, but soon the participants asked her to get more involved and make a presentation on the importance of her food.

During the pandemic, Cano began giving away food from her food truck instead of selling it. Every Monday she, along with the Native Connections organization and the Cihuapactli Collective, prepares natural organic food and personal care packages to deliver to those in need.

The short- and long-term benefits of growing her own food, Amelia Garcia says, include building a strong immune system and knowing what she puts inside her body. (Photo by Scianna Garcia/Special for Cronkite News)

“We know that there is a problem with the accessibility of food, and the pandemic has intensified it, showing that food systems do not work,” Cano said.

Amelia Garciía, in turn, created a farm in her backyard, which is why she was chosen to collaborate with Cano and the others on the food action plan.

Healthful foods are the best source of energy for the brain and blood, Garcia said, adding that eating foods that are unhealthful and full of genetically modified organisms can block receptors in the brain, which can result in poor decision making.

“You are what you eat,” she said. “If you’re quick, easy, and cheap, that’s how you’re going to live your life. But if you take the time to grow and understand your food, and nurture your knowledge of what you are growing, then you will, in turn, feed your mind.”

As part of the plan, Phoenix is funding community and grassroots organizations to provide food assistance to families affected by COVID-19 and will continue to do so through 2023.

Preservation of farmland and backyards also has been a focus point in the plan, and the city has already been able to put gardens in 100 homes in south and west Phoenix.

The women’s collective that helped develop the Phoenix Food Action Plan will continue to try to eliminate food deserts in Phoenix and combat accessibility issues faced by many.