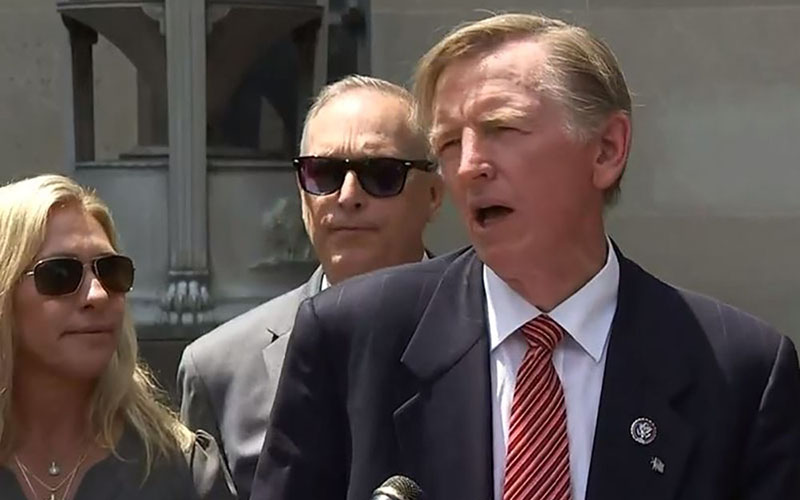

From left, GOP Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia and Andy Biggs and Paul Gosar of Arizona, at a July 2021 event where they said defendants in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol were “political prisoners.” The House members are among five lawmakers, including Arizona Rep. Mark Finchem, R-Tucson, whose involvement in Jan. 6 has sparked lawsuits charging that they should be disqualified from the ballot. (Photo courtesy C-SPAN)

WASHINGTON – A federal court said Georgia voters can press their claim that Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s support for the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol disqualifies her from the ballot, the same charge that has been filed against three Arizona lawmakers.

Monday’s ruling gave hope to the group that is pressing the claims, Free Speech for People, after a federal judge in North Carolina temporarily blocked a similar lawsuit the group filed against Rep. Madison Cawthorn, R-N.C.

But legal experts said that even if the cases are allowed to proceed, it will be difficult to show that the targeted lawmakers – including Arizona state Rep. Mark Finchem and U.S. Reps. Andy Biggs and Paul Gosar – actively participated in an insurrection that would make them ineligible to hold office.

“We … should be wary of labeling this kind of protest an ‘insurrection,’ which I think connotes the taking up of arms against the government,” said Ilan Wurman, an associate professor at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law.

“One can think the events of Jan. 6 were bad … and even that some participants sought to prevent the peaceful transfer of power,” Wurman said in an email. “But I’m skeptical that most courts will call that an insurrection.”

But Ben Clements, chairman and senior legal adviser at Free Speech for People, said it would be “hard to conceive” of a scenario in which the lawmakers’ actions would not be considered an insurrection.

“We believe the evidence is very strong that … those three who have been challenged there in Arizona did engage in insurrection,” Clements said Tuesday.

A spokesman for Gosar previously said the office would not comment on the case. Requests for comment Tuesday from Finchem’s and Biggs’ offices were not immediately returned.

All five cases are backed by Free Speech for People, but filed by constituents of the Republican lawmakers, including voters in Finchem’s Legislative District 11, Biggs’ congressional District 5 and Gosar’s congressional District 9.

All five make variations of the same claim, that the representatives’ involvement in the planning of or participation in the Jan. 6 protests disqualify them from holding office under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment. That section says that any lawmaker who took an oath to defend the Constitution would be ineligible for office if they “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” against the government.

Both Greene and Cawthorn moved to block the lawsuits against them.

A judge in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina ruled in Cawthorn’s favor last month. Chief Judge Richard E. Myers agreed with Cawthorn that Congress in 1872 reserved for itself the power to decide who has participated in an insurrection, and that the North Carolina State Board of Elections could not make that determination in relation to Cawthorn’s candidacy.

But a judge in the Northern District of Georgia rejected a similar claim by Greene.

U.S. District Judge Amy Totenberg said she was “skeptical” of Myers’ ruling that the 1872 law was proactive. She wrote that “pure common sense” dictates that the law was meant to apply to insurrection that “had already been incurred, rather than to all insurrectionists who may incur disabilities under that provision in the future.”

Totenberg went on to say that Greene had failed to show that letting the case go forward would impose a burden “beyond the merely inconvenient.”

The case is set to go forward Friday before a state administrative law judge. But Greene did win one victory in that case, when the judge agreed that the burden of proving that Greene took part in an insurrection was on the voters who filed the suit, and not on Greene to prove otherwise.

“The only burden on Plaintiff at this stage is her participation in an expedited, streamlined administrative review process, in which the burden of proof has now been placed on Intervenors,” Totenberg wrote.

That will be a tough burden for the voters to prove, said Paul Bender, a law professor at ASU. He said that attorneys for the lawmakers could argue that the Jan. 6 protesters “wanted Trump to be elected by constitutional means.” While that may be “an attempt, illegally, to change an election result, that’s not the same as an insurrection.”

“If they marched into the White House and told the president that he had to leave and took over the government, that’s an insurrection,” Bender said. “But these people … weren’t doing anything like that.”

Wurman thinks it is a stretch for liberals to invoke the 14th Amendment’s language against insurrection in this case, just as it’s a stretch for conservatives to call the surge in immigrants an “invasion” for constitutional purposes. “I think that’s silly,” he said.

Clements said it is not a stretch at all.

“The participants have, in many cases, acknowledged that their purpose was to stop the constitutionally required process of Congress certifying the results of the election,” he said. “It’s hard to conceive of a more direct challenge to our government.”

Clements said his group has appealed the ruling in Cawthorn’s case to the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, and is confident the courts will eventually agree with the voters.

“We’re hopeful that … after the Fourth Circuit acts, we will in fact be 2-0 on those as opposed to 1-1,” he said.