The border wall divides Nogales, Arizona, from Nogales, Sonora, shown here on April 13, 2022. (Photo by Genesis Alvarado/Cronkite News)

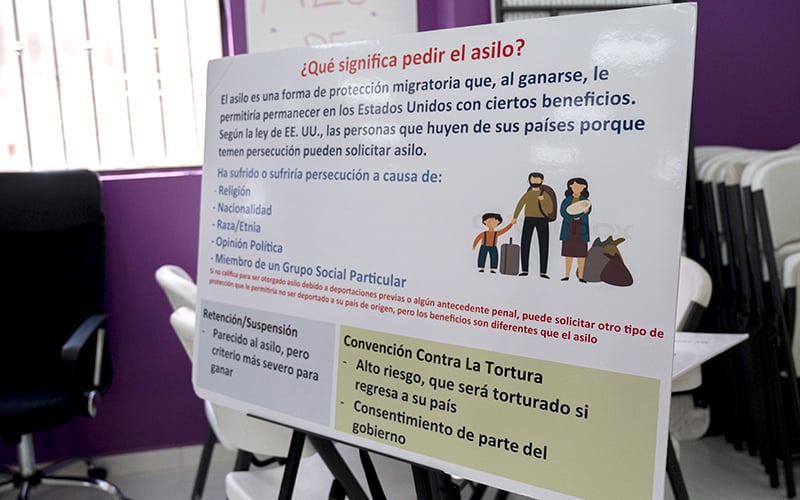

An infographic inside the Kino Border Initiative explains what it means to ask for asylum, in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico on April 13, 2022. (Photo by Genesis Alvarado/Cronkite News)

The Last Supper is depicted with immigrants inside the dining room of the Kino Border Initiative in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico on April 13, 2022. (Photo by Genesis Alvarado/Cronkite News)

Jesuit priest the Rev. Max Landman organizes clothes and shoes inside the Kino Border Initiative in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico on April 13, 2022. (Photo by Genesis Alvarado/Cronkite News)

NOGALES, Sonora, Mexico – Rosario, 24, married as a teen, had two children and raised them while her husband worked. It took him eight years to earn enough money to furnish their home in the southern Mexican state of Michoacán. But it was a nice home. They fulfilled their dream.

Then warring cartels forced them to flee.

“We left everything overnight, we couldn’t bring anything with us,” said Rosario, who only uses her first name for fear of being identified. “I cried a lot and wondered, ‘Why did this happen to us?’”

Now the family has been waiting almost a year in Nogales, Sonora, on the Arizona border, to apply for asylum, a process shut down almost completely in March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

While they wait, they can’t find work and their children can’t go to school. They suffer discrimination from local residents when looking for housing or a way to get by.

“I had a home in Michoacán, a good life,” Rosario said. “My husband and I got married and we built a beautiful life together, but we had to leave. We dropped everything in order to just feel secure again.”

Rosario, 24, an asylum seeker who only wants to use her first name for protection, says violence pushed out of her home state of Michoacán. She talks to a Cronkite News reporter in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico on April 13, 2022. (Photo by Genesis Alvarado/Cronkite News)

Such are the stories of thousands of immigrants waiting along the U.S.-Mexico border for the lifting of Title 42, a policy enacted by the Trump administration that closed the border to migrants and asylum seekers as a public health and safety measure during the pandemic. Since then, more than 1.7 million migrants have been turned away.

On April 1, President Joe Biden ordered Title 42 lifted on May 23. But he has been blocked from all sides, including members of his own party, who say Homeland Security and U.S. Customs and Border Protection are not prepared for the onslaught of people expected when the U.S. allows asylum applications again after two years.

Rosario’s family came to the Kino Border Initiative for breakfast on Wednesday, and stayed a bit afterwards to collect the Easter toys that were being handed out to the children. Families sat in the dining hall of the facility and shelter that sits directly across from a border crossing and ate, while children ran around and played with the volunteers.

On the second floor, there’s a closet full of blankets, pillows and sheets, and another filled with clothes neatly folded and organized by age and size. Next to that are the dorms — multiple bunk beds placed together, looking out on the common area.

Outside the shelter, milling with other asylum seekers, single mother Luz watched her three kids play with the new stuffed bunnies they got in their Easter baskets from Kino. She too only wanted to use her first name.

Luz fled the southern state of Guerrero after being threatened by a drug gang. She and her children are waiting to seek asylum in the U.S. because it’s the only place where they’ll be safe from cartel violence.

“We’re waiting in fear,” Luz said. “We’re just waiting on President Biden’s decision. We can’t wait for too long here because we can still be targeted while we’re over here.”

Families like Rosario’s and Luz’s are living with the consequences of a political fight in Washington that can’t agree on a solution.

“Title 42 is not stopping migrants from getting into the U.S.,” Rosario said. “There are still people dying in the desert. We just want President Biden to listen to us and for people to walk in our shoes for a day.”

Kino Border Initiative volunteers, Kamila Puzinaite and Lisa Elmaleh, serve lemonade to migrants who are eating breakfast in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico on April 13, 2022. (Photo by Genesis Alvarado/Cronkite News)

No one knows what’s going to happen next. Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich filed suit against the Biden administration April 3 for its decision to lift Title 42.

Brnovich, along with the attorneys general of Louisiana and Missouri, filed the suit in the U.S. Western District Court of Louisiana, arguing that Biden violated federal procedures by finalizing legislation without publishing notices in the Federal Register beforehand.

Meanwhile, a bipartisan group of U.S. senators, including Arizona Democratic Sens. Mark Kelly and Kyrsten Sinema, have introduced the Public Health and Border Security Act, which would require Title 42 to stay in place at least until 60 days after the Surgeon General notifies Congress that the public health emergency declared for COVID-19 can be lifted. After that, the Department of Homeland Security would have 30 days to submit a plan to Congress to address a surge of migrants at the border.

A similar bipartisan bill in the House includes Arizona Democratic Reps. Tom O’Halleran of Sedona and Greg Stanton of Phoenix as co-sponsors.

“Many expelled migrants have been waiting in limbo for months or years in dangerous locations, making them vulnerable to exploitation,” the two Arizona senators wrote in a letter to Biden. “At the same time, chaos at the border in a post-Title 42 scenario also negatively affects migrants’ safety and could further strain an already overwhelmed health care system at the border.”

There’s no exact number of how many people are waiting in Nogales. It’s a fluid population, said Gia Del Pino, director of communications at the Kino Border Initiative. Some leave and try other ports of entry, but none of them can go back home, she said.

“This is not a sustainable place to live for people,” Del Pino said. “The government likes to believe, ‘Well, you fled, you’re here at the border, stay at the border. You don’t need asylum.’ And that’s not the case.”

Victor, another asylum seeker who only wants to use his first name, says he doesn’t want to be at the border, he has to be there in search of security, in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico on April 13, 2022. (Photo by Genesis Alvarado/Cronkite News)

The numbers always change at Kino, as well as the countries and places the migrants are fleeing. Last summer, the shelter served on average 1,000 meals every day as a surge of asylum-seekers came from Michoacán and Guerrero, Del Pino said, two states hit particularly hard by cartel violence and home states for Rosario and Luz. Residents of these Mexican states are becoming victims of displacement due to criminal groups battling for control over territory. According to a recent article in the Washington Post, as many as 20,000 people have fled Michoacán in the last year.

Courtney Smith, a 22-year-old volunteer at Kino, said she was excited and looking forward to Joe Biden being elected president, thinking he would fix the problem at the border, but she hasn’t seen much change.

Originally from Connecticut, she has been a volunteer at Kino since September and said it opened her eyes to a complicated situation that leaves people trapped.

“I’ve been really disappointed with the lack of care and lack of focus on the humanitarian crisis here,” Smith said. “I thought that things were going to get better, but they’ve either stayed the same or have gotten worse, and that’s been really hard.”

Victor is another migrant who fled cartel violence. Also using only a first name, he said his son was threatened and was the victim of a shooting in his hometown in Guerrero.

While he has managed to find work, he doesn’t earn enough to provide for his family. He said he’s not safe in Nogales because the cartel from his hometown is still able to track him down.

“We aren’t here because we want to or because we like to be here,” Victor said. “We’re here because we have to be in order to survive.”