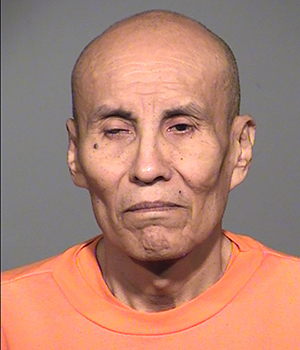

Arizona has carried out most executions with lethal injection since 1992, but problems with a 2014 execution had halted them since then. Clarence Dixon, whose execution date was set for May 11, will have the choice of being put to death by injection or in the state’s gas chamber if his sentence is carried out. (Photo courtesy Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry)

WASHINGTON – The Arizona Supreme Court set May 11 as the execution date for Clarence Dixon, a rapist and murderer who would become the first inmate put to death in Arizona since a badly botched lethal injection in 2014.

Unless he opts for the gas chamber – which the state restored after its botched execution of Joseph Wood eight years ago – Dixon would be put to death with an injection of “a substance or substances in a quantity sufficient to cause death,” according to the death warrant issued Tuesday by the court.

Attorney General Mark Brnovich said Dixon has exhausted all his appeals and his death sentence should be carried out.

“I made a promise to Arizona voters that people who commit the ultimate crime get the ultimate punishment,” said Brnovich in a statement this week. “I will continue to fight every day for justice for victims, their families, and our communities.”

But Dixon’s attorneys pointed to the state’s “history of problematic executions” and called it unconscionable that the execution could be carried out while questions remain about the procedure and about Dixon’s mental and physical health.

Arizona death-row inmate Clarence Dixon was already serving life for a sexual assault when DNA linked him to the 1978 murder of a woman in Tempe. (Photo courtesy Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry)

“The state has had nearly a year to demonstrate that it will not be carrying out executions with expired drugs but has failed to do so,” said a statement from Jennifer Moreno, the attorney. “Under these circumstances, the execution of Mr. Dixon – a severely mentally ill, visually disabled, and physically frail member of the Navajo Nation – is unconscionable.”

This is not the first time Brnovich has tried to get an execution date for Dixon. He asked the Supreme Court last year to issue warrants of execution for both Dixon and Frank Atwood, who kidnapped and murdered an 8-year-old Tucson girl in 1984. Brnovich said Atwood, like Dixon, had exhausted his appeals and he was pushing for execution dates as early as last fall.

Those cases were derailed, however, when the state acknowledged that the pentobarbital it had obtained for the executions would have passed its expiration date by the time the executions could be scheduled.

The latest warrant does not indicate what drugs would be used in Dixon’s case, and Brnovich’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Dixon was already serving seven life terms for his 1985 convictions on sexual assault charges when his DNA was matched to a previously unsolved 1978 rape and murder of an Arizona State University student in Tempe. Deana Bowdoin’s boyfriend found her dead in her Tempe apartment early on the morning of Jan. 7, 1978. She had been raped, strangled and stabbed to death.

Dixon was charged with Bowdoin’s murder in 2002. He was convicted in 2008 and sentenced to death because of his prior life sentence and because Bowdoin’s killing was an “especially cruel, heinous or depraved” crime.

While he has been in prison for 36 years, Dixon has been on death row for just 14 years. His execution, if carried out, would come sooner than most: The Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry said the average length of stay on death row since 1992 is 17.4 years. There are currently three women and 109 men on death row in Arizona.

Wood was the last inmate executed by lethal injection in Arizona, when the state administered a “cocktail” of medications: midazolam and hydromorphone, a combination that had led to problematic, drawn-out deaths in two previous executions in Ohio and Oklahoma.

Wood’s execution required 15 injections and lasted two hours, during which he repeatedly gasped and snorted on the gurney, according to witnesses present. Then-Gov. Jan Brewer ordered a review of the execution by the corrections department, which ultimately found that it had followed proper procedure and that Wood did not suffer, despite appearances.

Its troubles with lethal injection, however, led the state to test its gas chamber, built in 1949 and last used in 1999, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. The chamber was restored after leaking seals were discovered, but the process angered critics who said the state planned to use a chemical related to the gas used during the Holocaust.

According to the death warrant, Dixon has until 20 days before his scheduled May 11 execution date to choose between dying by lethal injection or lethal gas. If he does not choose, he would be executed by lethal injection.